Shelburne Museum A Unique Vision

|

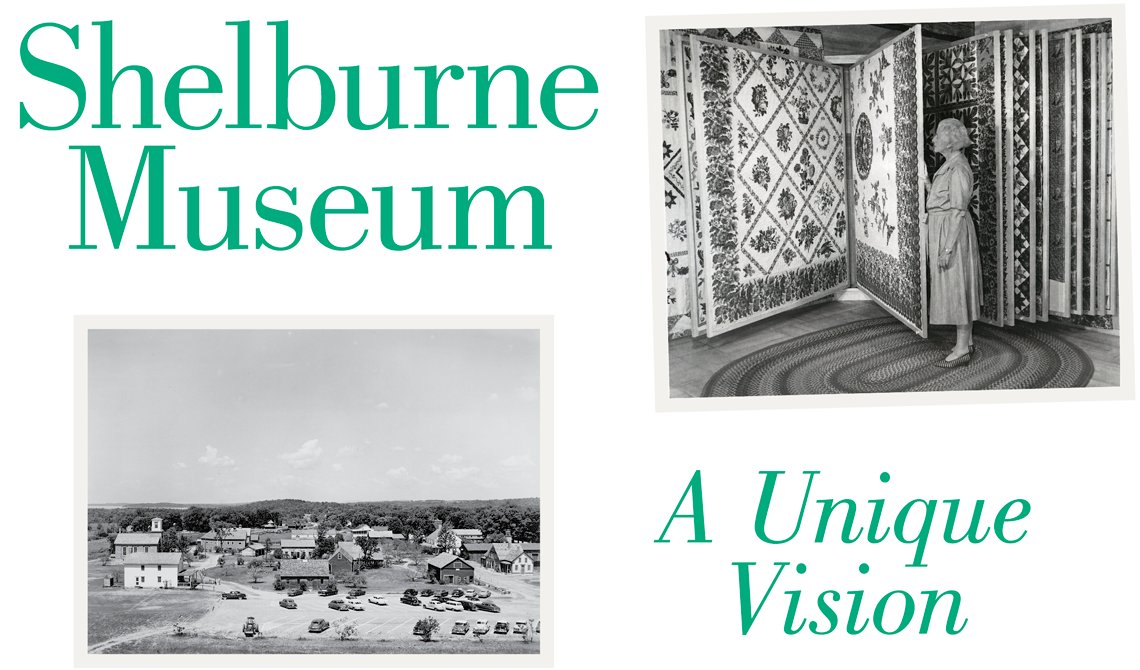

| Right: Fig. 1: Einars J. Mengis, Electra Havemyer Webb with quilt display in Dana-Spencer Textile Gallery at Hat and Fragrance, (PS1.10-Webb, E.3). Left: Fig. 2: Unidentified photographer, Aerial View of the Museum, 1954 (PS4.1-507). |

Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, Vermont, is the remarkable result of one trailblazing person’s lifelong passion and profound commitment to a unique vision. Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888–1960) was a woman of unparalleled fortitude and taste who stood out as one of the few woman collectors in her time as well as one of the earliest collectors of what we now know as American folk art (Fig. 1). Seventy-five years after she founded Shelburne Museum, Mrs. Webb’s “educational project, varied and alive” stands as a testament to its founder’s innovation in both the art and museum fields.

Webb’s vision was for a place that was approachable, accessible, and committed to history, art, and learning. No project was too complicated when it came to realizing her vision. What started as one original building (what is now Variety Unit) grew to 39. From Dorset House to the Lighthouse to Stagecoach Inn to the Covered Bridge — 25 buildings appeared on flatbeds, in pieces to be reassembled, or in the case of the steamboat Ticonderoga on railroad tracks laid for the purpose of moving the boat two miles over land from Lake Champlain. One can imagine. It was an exciting time (Fig. 2).

In the 1980s that intrepid spirit was in full effect, witness the silo for Round Barn arriving by helicopter. In 2013, the Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, inaugurated year-round operation and, by adding new state-of-the-art galleries and classroom space, opened up the institution to new audiences (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3: The Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education is the Museum’s newest structure, opened in 2013. |

Vivacious and determined, Electra Havemeyer was born to European and Asian art collectors H. O. and Louisine Havemeyer, whose wealth was derived from the sugar industry. She lived a life of privilege in New York City and traveled often, including trips to Paris to spend time with family friend and art advisor the Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt. When Electra began collecting art at age 19, she diverged from her parents’ interests by acquiring a piece of American folk art, a tobacconist figure. She collected art that was created not by formally schooled European artists but ordinary craftsmen and artisans in the United States. Few other collectors saw value in “the beauty of everyday things” as she did. In focusing her collection on folk art, the collector preserved pieces of American life and created a uniquely American aesthetic that challenged the preference for European styles at the time.

In 1910, she married James Watson Webb, whose wealth came from the railroad industry and whose father founded Shelburne Farms. This brought Mrs. Webb to Vermont. Here she built a museum to share her collections with others and promote art and history education based on the principle that art not only could be created by anyone but also should be available to all. Her belief in broadening access to enthralling and experiential learning remains a core component of the museum’s mission to this day.

From her first folk art purchase to one of her final acquisitions, Andrew Wyeth’s Soaring, the unexpected defined Mrs. Webb’s collecting. Throughout her life, she pursued objects that affected her aesthetically and emotionally, whether a coverlet, a house, or a turn-of-the-century carousel. Given Mrs. Webb’s capricious taste, it is not surprising that Shelburne Museum is equally whimsical and that to visit the campus is to enter a dreamlike landscape of historical buildings, gardens, and other surprises. Where else, after all, can we find a steamship docked in a grassy landscape, a horseshoe-shaped barn filled with 19th-century carriages, or a hunting lodge replete with taxidermied animals, all within the same museum campus?

|

Fig. 4: Claude Monet, Le pont, Amsterdam (The Drawbridge, Amsterdam), 1870–71. Oil on canvas, 21 x 25 in. Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb (Fund, Inc., 1972-69.5). |

Leaving a Lasting Impression

| |

Fig. 5: John Frederick Peto, Ordinary Objects in the Artist’s Creative Mind, 1887. Oil on canvas, 56⅜ x 33¼ in. Museum purchase, acquired from Maxim Karolik.1959-265.33. Photography by Bruce Schwarz. |

The story of Shelburne Museum’s Impressionist paintings collection is a generational one that ties the museum’s past to its present. In 1929, Mrs. Webb inherited many of her parents’ Impressionist paintings, including works by Claude Monet (Fig. 4), Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet. Years later, Mrs. Webb was determined to bring her parents’ Impressionist collection to Shelburne Museum and planned to construct a new building to house the paintings and share them with others. One of her sons, James Watson Webb Jr., fulfilled his mother’s wish in a way that linked three generations of his family to their shared heritage of collecting and recognized its significance to the museum’s story. Following Mrs. Webb’s death in 1960, James became the museum’s president and oversaw construction of the new Electra Havemeyer Webb Memorial Building to display the Impressionist paintings. Watson recommended modeling the building’s interior after the rooms in his childhood home in New York City, where he and his four siblings — like their mother before them — had grown up surrounded by art. The Electra Havemeyer Webb Memorial Building is the only place in Vermont where visitors can find world-class Impressionist art on public display.

Collecting with Purpose

Just as Electra Havemeyer Webb’s parents collected French Impressionist paintings at a time when the works were not highly sought after on this side of the Atlantic, Mrs. Webb turned her attention to collecting 19th-century American paintings late in life at a time when few others were (Fig. 5). In the late 1950s, most collectors were investing in European modernism or abstract paintings.

Nevertheless, Mrs. Webb followed her father’s example and continued to collect items that appealed to her regardless of popular opinion. Driven by the visual appeal as much as the history and value of potential acquisitions, she joked about not being able to hold back when it came to acquiring new things. But in fact, Mrs. Webb collected quite strategically and with great foresight, and she assembled her American paintings collection with the intention of juxtaposing well-known American artists with lesser-known painters. Her relationships with art dealers like Edith Halpert, who displayed both folk art and American modernist works at her Downtown Gallery in New York City, greatly influenced Mrs. Webb’s collecting. Ultimately, Mrs. Webb built an impressive and thoughtfully curated American paintings collection that tells an abundance of stories about American life and culture.

|

Fig. 6: Unidentified maker, Harvard Chest, 1700–25. Painted pine and brass, 44 x 38½ x 21 in. Gift of Katharine Prentis Murphy and Edmund Astley Prentis (1956-694.8). Photograph by J. David Bohl. |

|

Fig. 7: Attributed to Warren Gould Roby, Mermaid Weathervane, 1850–75. Pine, paint, brass, iron, and metal, 25 x 53 x 5 in. Museum purchase (1952. 1961-1.23). Photography by Andy Duback. |

Art of the People

| |

Fig. 8: Unidentified maker, Jack Tar Ship Chandler’s Trade Sign, ca. 1860–70. Carved and painted wood, 61 x 27 x 24 in. Gift of Dr. L. J. Wainer (1962-24). |

Electra Havemeyer Webb was one of the earliest collectors of American folk art, or art crafted by ordinary people who used and lived with the objects they made. She noted later in life that she “wanted to collect something that nobody else was collecting. . . . At that time, nobody wanted Americana, so I started buying and I’ve never stopped.” Mrs. Webb traveled throughout New England in search of folk art, and by the 1940s she was buying from such prominent dealers as Edith Halpert at the Downtown Gallery in New York City.

Shelburne Museum’s pioneering collection of 18th- and 19th-century American folk art is one of the finest in the nation and is currently being reinterpreted in historic Stagecoach Inn, which reopened to the public this year following a conservation project. Examples of painted furniture (Fig. 6), weathervanes (Fig. 7), whirligigs, tobacconist figures, trade signs (Fig. 8), ships’ carvings, and scrimshaw, many by unknown makers, are highlights of the refreshed installation. They are joined by extraordinary paintings by many of the best-known artists of the American folk art tradition: Erastus Salisbury Field, Edward Hicks, Ammi Phillips, Joseph Whiting Stock, and — of course — Anna Mary Robertson (“Grandma”) Moses.

“My interpretation [of folk art] is a simple one,” wrote Mrs. Webb in 1955. “Since the word ‘folk’ in America means all of us, folk art is that self-expression which has welled up from the hearts and hands of the people.” That combination of heart and hand is the defining character of Shelburne Museum’s collection of American folk art.

Art with a Function

Like many objects that we now think of as folk art, hunting decoys were created not just to be looked at but to be used in a very specific way. Even today, hunters use wild-fowl decoys to create the illusion of a safe place for ducks and geese to congregate, thereby setting a trap that makes the birds easy targets for a nearby shotgun (Fig. 9).

|

Fig. 9: Captain Charles Christopher Osgood, Osgood Canada Goose Decoys, ca. 1849. Wood, paint, metal, and leather. Gift of Mrs. P.H.B. Frelinghuysen (1953-301.5, 4 & 3). Photography by RL Photo. |

Before the age of mass production, decoys were carefully handcrafted; carved from wood and then strategically painted to look like their real-life counterparts. Sculptors’ creations represented the diversity of avian life in North America and often imitated land-and-water dwellers such as ducks, geese, swans, and shorebirds. As mass-market versions and alternative hunting techniques took over in the 20th century, the old-style decoys became highly collectible and Shelburne Museum’s collection numbers more than 1,200, 400 of which were acquired in 1952 from Joel Barber, a New York City architect, artist, and carver, was among the first to promote decoys as a uniquely American art form with his 1934 book, Wild Fowl Decoys.

Setting a Pattern

| |

Fig. 10: Attributed to Emeline Barker, Applique and Pieced Mariner’s Compass and Hickory Leaf Quilt, ca. 1860. Cotton, 100 x 96 in. Museum purchase, acquired from Florence Peto (1952-545). |

Shelburne Museum’s extraordinary textile collection interweaves intricately stitched pieces from across states and centuries. Electra Havemeyer Webb helped pioneer the study of American textiles and was among the very first to exhibit them as works of art. She was attracted to their bold, graphic patterns, intense colors, and imaginative combinations of design elements, often whimsical and out of scale. The still-growing collection she began at Shelburne is remarkable in its size and quality and includes quilts, woven coverlets, needlework, hooked rugs, and printed fabrics from the 18th century to the present.

The fact that a woman championed the cause of textiles as an art form was very apropos, considering that women handcrafted many of the historic and contemporary items in the museum’s textile collection. In the 18th and 19th centuries, most women were expected to craft the bedclothes, draperies, and apparel their homes and families required. The quilts and other bedcoverings that women created were a critical necessity in poorly heated early American homes. Many of these functional pieces are part of the museum’s collection of more than 600 American-made quilts today.

The museum’s quilts are world renowned for their exceptional variety and high quality (Fig. 10). The collection focuses on New England and Northern states, but it also includes other distinctive examples, including quilts from the South and Midwest as well as the Amish and Mennonite communities of Pennsylvania and Ohio. Featured techniques in the collection include album, appliqué, chintz, crazy, pieces, whitework, and whole-cloth. The diversity of methods and materials demonstrates not only the richness and variety of quilting traditions across time but also the creative possibilities of building and expanding upon them.

Museum visitors can enjoy rotating exhibitions of the quilts, in addition to hooked rugs, woven coverlets, and samplers in the Dana-Spencer Textile Galleries. Most of the pieces in these collections were produced in 19th-century New England. Notable 20th-century examples include a remarkable group of 50 statehood rugs by Molly Nye Tobey (1893–1984) and a collection of contemporary hooked rugs by Patty Yoder (1943–2005).

A Whimsical Experience

Mrs. Webb’s circus collection provides an overview of circus and childhood material culture. She was so delighted with her acquisition of the miniature Arnold Circus Parade in 1959 that she had an utterly unique, horseshoe-shaped building designed to display it. The parade extends nearly the entire 518-foot length of the Circus Building. In time, that same building has come to house many additional circus acquisitions as well, including the Kirk Bros. Circus, a 3,500-piece carved miniature three-ring circus with an audience. The collections also include more than 500 historic circus posters from Barnum and Bailey, Ringling Brothers, and other major shows.

|

Fig. 11: G.A. Dentzel Carousel Company, Carousel Horse, ca. 1902. Carved and painted wood, 59 x 60 in. Museum purchase (1951-392.30). Photography by Andy Duback. |

Historically, circuses and carousels did not have much to do with one another. However, both carousels and circuses were popular entertainments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and both were highly sensory experiences — a whirl of color, movement, and glittering surfaces, accompanied by music. Mrs. Webb surely responded to these visual qualities in the circus-themed objects she acquired for her museum.

In that sense, it seems perfectly logical that the Circus Building today also contains approximately 40 different turn-of-the-century carousel figures made by the Gustav Dentzel Carousel Company of Philadelphia (Fig. 11): lions, tigers, deer, and ponies that are the near life-size counterparts to the miniatures in the Arnold parade and the Kirk circus. Outside, visitors can climb aboard an operating 1920s carousel made by the Allan Herschell Company of North Tonawanda, New York, and be a part of the historic fun.

Stagecoach Inn Reopening

|

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Shelburne Museum’s opening, Stagecoach Inn’s galleries have been refreshed and reinstalled with iconic selections representing the best of the folk art collection and honor Webb’s early vision, assembled to encourage visitors’ curiosity and bring light and life to vernacular American life (Fig. 11). Built in 1783 the building was used as an inn in Charlotte, Vermont, along the main stage route to Montreal. Relocated to Shelburne Museum’s campus in 1949, its galleries have displayed folk art since 1951.

New research looks past the formal qualities of the material on display and digs into the origins, makers, and functions of these objects to offer 21st-century perspectives reflective of the vast and varied ingenuity and creativity that inflects America’s rich visual story.