The Archetypal Landscapes of Rockwell Kent

This archive article was originally published in the Late Summer 2005 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

American painter Rockwell Kent (1882–1971) reveled in the spiritual energy of remote wilderness. Grounded in the writings of the nineteenth-century American transcendentalists who celebrated the divine rhythm of the natural world and its intuitive mysteries, Kent painted and wrote from rugged and forbidding places, often at the ends of the Western hemisphere. His portrayals of land and sea pull the imagination away from the present to a mythical, timeless realm. At midcareer in 1924, Kent associated the spiritual epiphany viewers might experience when looking at his elemental landscapes with the loss of self-consciousness described by Saint Augustine in his Confessions: “And the people went there and admired the high mountains, the wide wastes of the sea and the mighty downward rushing streams, and the ocean, and the course of the stars, and forgot themselves.”1 Collector Duncan Phillips, an early champion of Kent’s work, considered Kent a mystical “nature poet” and “incomparable as a painter of majestic mountain landscapes, of space, of solitude, and of thrilling skies and lights.”2

Kent’s early twentieth-century paintings of land and sea are an integral part of the accomplished American landscape tradition forged in the nineteenth century by such painters as Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, and Fitz Hugh Lane. These painters were also inspired by the transcendence and divinity they found in uncharted lands, where nature is often indifferent to the measure of humankind. Kent, and others among the first generation of American modernist painters that included Georgia O’Keeffe and Marsden Hartley, advanced this landscape tradition through innovations in color and form.

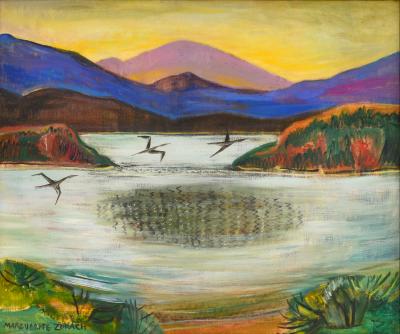

Kent demonstrated an early aptitude for the rigor and beauty of plein-air painting. At age 18 he began a course of summer study with William Merritt Chase at his school on Long Island at Shinnecock Hills. He returned for two succeeding summers and was awarded a scholarship to the New York School of Art. In the summer of 1903, Kent moved to Dublin, New Hampshire, serving as a studio assistant to Abbott Handerson Thayer, who further cultivated his interest in the drama of the natural world. The symmetry and calm of Dublin Pond (Fig. 1) show the influence of both Chase and Thayer as well as that of Arthur Wesley Dow, another of Kent’s early teachers. A proponent of the structures and aesthetics underlying Japanese composition and design, Dow offered an innovative approach to reordering, rather than replicating, nature. Reflected water, as seen in Dublin Pond, was among the many Japanese devices favored by Dow, particularly in his color woodcuts from the 1890s of bridges over the Ipswich River. The work was included in the Society of American Artists exhibition in 1904, the first public exhibition of Kent’s work, where it was acquired by Smith College Museum of Art.

- Fig. 2: Rockwell Kent (1882–1971)

Afternoon on the Sea, Monhegan, 1907

Oil on canvas, 34 x 44 inches

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Museum purchase, Richard B. Gump Trust Fund, Katherine Hayes Trust Fund, Art Trust Fund, and Unrestricted Art Acquisition Endowment Income Fund, and partial gift in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Langdon W. Post, 1994.107

Completing his studies at the New York School of Art in the spring of 1905, Kent heeded the advice of his teacher Robert Henri to journey to Monhegan Island, ten miles off the coast of Maine. Awestruck by the island’s monumental headlands and restless seas, Kent committed the emotional experience to canvas.

He produced powerful paintings for the next five years, reaching early artistic maturity. In Afternoon on the Sea, Monhegan (Fig. 2), he portrays the offshore island, Manana, with regal splendor; the massive primordial rock presides over the lobster fishermen and the glinting waves on which they ride. The chromatic gradations of the blazing sky, the simplicity of form, and the dynamic play of color define this and other early Monhegan paintings as radical and modern. Late Afternoon, Monhegan Island (Fig. 3) captures the solid mass of Manana melting in the blinding light of the radiating sun. Arthur B. Davies considered these and two other early Monhegan paintings by Kent to be “masterpieces”; critics and other colleagues, including George Bellows, recognized Kent as a force with which to be reckoned.3

Over the course of thirty years, Kent evolved as a painter of distinction, living and painting on windswept islands, whose isolated geographies further separated the here and now from the beyond. He always returned from his painting expeditions to the nexus of New York City, where he kept abreast of the European avant-garde and interacted with fellow artists, dealers, critics, and patrons of his work. After the historic exhibition of modern art in New York—the Armory Show of 1913—Kent resolved to advance his work and move further away from verisimilitude to reshape the natural world. He moved to Newfoundland in the early months of 1914 where he imaginatively constructed richly textured meditations on ponderous themes—suffering, death, and the afterlife. Modernist collector Ferdinand Howald purchased a few of these works, including Pastoral (Fig. 4), an organic tapestry of creation that conveys a somber mood reflecting the artist’s interior state. In the center is a majestic stag; other modern artists, notably the German painter Franz Marc and the French sculptor Elie Nadelman, also featured the wild stag, apparently believing that it has an independent soul and is aware of truths inaccessible to humankind. On the right, a naked figure nestles into the furrow of a mound, one hand supporting its face, as though in sorrow. Spectral figures, often writhing in anguish and conveying an expressive universe of grief, populate many of Kent’s paintings from Newfoundland, which were first exhibited in 1917 at the Daniel Gallery in New York. Imbued with many layers of meaning, these haunting works were galvanized by an historic double tragedy Kent experienced with his Newfoundlander neighbors that winter—the loss of more than 200 sealers aboard ships ravaged by a storm at sea.

The spirited life and work of poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892) influenced Kent and others of his generation of painters, including Marsden Hartley, who considered Whitman a “genius” as well as a “modern pioneer.”4 Whitman inspired artists to experiment with paint as he himself experimented with language. Robert Henri quoted liberally from Leaves of Grass as an inspirational bible. In 1919, on the eve of the centenary of Whitman’s birth, Kent painted Pioneers (or Into the Sun) (Fig. 5) from his fall and winter home on Fox Island in Resurrection Bay, Alaska. There, together with his 9-year-old son, he communed with the forces of nature, including a frozen waterfall, primordial spruce, and distant Bear Glacier. Many of his ink drawings from Fox Island exalt the pioneer challenges he and his son routinely confronted. He also completed there a little known series of seven mystical brush and ink drawings, which are imbued with Eastern spirituality and evidently influenced by the ancient Hindu text Bhagavadgita.

After exhibiting his drawings and paintings from Alaska at M. Knoedler and Co. in 1919 and 1920, respectively, Kent remained in the United States for a few years before setting out in 1922 for the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America. There he further simplified the organic structures of nature, attuning his palette to the muted, icy scenes and inhospitable climate. His compositions eschewed the human figure; instead, glaciers, mountains, mountain lakes, and rough waters became his protagonists. A nonconformist spirit permeated these works, offering no foreground shoreline as visual foothold. Instead, viewers were cast aboard the artist’s small boat to share his vantage point and his fear. Among the paintings he brought back to New York and exhibited at Wildenstein Galleries in 1925 is Admiralty Sound, Tierra del Fuego (Fig. 6), which exemplifies the artist’s ability to convey the abstract qualities of light on distant water.

Kent voyaged to Greenland in the summer of 1929, fulfilling his lifelong ambition to visit the land of ancient Norse legend. The 33-foot-long, oak-keeled boat he shared with two sailing companions shipwrecked off the coast of Greenland, an episode he vividly recalled in his third illustrated adventure memoir, N by E (1930). He returned to Greenland in the summers of 1931 and 1934, each time staying through the darkness of winter above the Arctic Circle where he flourished as a painter and watercolorist. There he wrote and illustrated a book based on his relationships with the Greenlanders. He titled this adventure memoir Salamina (1935) after his beautiful Greenlander housekeeper who, together with her young children, shared his one-room habitation.

Envisioning Greenland as heaven, Kent further abstracted the geometries of the natural world–with wide swaths of immutable rock above a snow-capped earth. Never exhibited in New York as a coherent body of work after they were completed, the paintings from Greenland represent, arguably, the culmination of Kent’s thirty-year-long engagement with modernism and a major contribution to modern American art. In Arrival of the Post (Fig.7), which Kent completed in his Adirondack studio several years after its conception in 1935, the postman—barely perceptible at center left—crosses the frozen sound on his sledge. Kent gave full expression to the transcendent force of nature by juxtaposing a social world in flux, diminutive Greenlanders anticipating the postman’s arrival, against the awesome geometries of the Earth and the infinite beyond. He endowed two distant glaciers, which he described as “curving highways of pale jade,” with the force of primordial symbols.

Kent’s touchstones for eternity, these glaciers were the backdrops to his natural stage where icebergs “perform” in the summer and fall. In Early November: North Greenland (Fig. 8), enormous faceted icebergs of turquoise-green translucence float by and offer compelling and constantly changing scenery in the treeless Arctic landscape. They soon freeze in place, evolving into organic skyscrapers for the winter and spring, and Kent captured their otherworldly sculptural qualities in many of his Greenland paintings and drawings.

After his third and final return from Greenland in 1935, and based at the Adirondack farmstead in upstate New York he built in 1928, Kent began to change his philosophy about the nature of art and its purpose in the cultural evolution of humankind. His turn away from “cosmic consciousness” and toward socialist ideology is reflected in his artistry as well as his writing. After World War II, Kent’s life and work ignited a firestorm of controversy, primarily because of his struggle against America’s anti-Soviet foreign policy. In 1960, as a gesture of his generosity and goodwill, Kent gave to the peoples of the Soviet Union several hundred of his paintings, drawings, and prints, including Arrival of the Post and Early November: North Greenland. Although this defiant act further diminished the artist’s reputation, his achievements are coming into sharper focus with the passage of time. The most accomplished of Kent’s archetypal landscapes, which he painted during his more than thirty years as a modernist, are abstracts of infinity. Imbued with mythic, often haunting qualities, they offer an interior portrait of Kent, an artist on the frontier of the American imagination.

—

Jake Milgram Wien, an independent curator and historian, is guest curator of Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern. He has written on Kent for books and scholarly journals. A graduate of Stanford, Oxford, and the University of California, Berkeley, he authored the catalogue accompanying The Vanishing American Frontier, a traveling exhibition he organized for the Montclair Art Museum (New Jersey) that opened in 1995.

This article was originally published in the Late Summer 2005 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Duncan Phillips, A Collection in the Making (Cambridge, Mass.: Riverside Press, 1926), 65–66.

3. Arthur B. Davies to Robert Henri, April 5, 1907. Henri Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library,Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

4. Marsden Hartley, “Whitman and Cézanne,” in Adventures in the Arts (1921; repr., New York: Hacker Art Books, 1972), 35–36.