The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi

Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889–1953) came to the United States in 1906 from his native Japan when he was sixteen years old. Encouraged by a high school teacher to study art, he went on to become one of the most esteemed painters in the New York art world during his lifetime. The Whitney Museum of American Art chose Kuniyoshi in 1948 for its first solo exhibition of work by a living artist and again featured his work in an exhibition in 1986. During the 1980s, Japanese collectors and museums recognized the artist’s achievement and began to collect his work avidly. Their enthusiasm culminated in a major exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum in 1989, which traveled to Okayama and Kyoto in 1990. Numerous smaller exhibitions of his work have been on view in both Japan and the United States since that time.

Kuniyoshi began showing his paintings publicly in 1917 while still a student at the Art Students League in New York. To help support himself financially during these years, he began taking photographs of other artists’ work (Fig. 1). As early as 1922, as awareness of his work increased, writer William Murrell included Kuniyoshi in a series of small monographic books he published about contemporary artists. “Yas,” as his friends affectionately knew him, knew everyone and moved easily among artists who worked in a variety of styles. Kuniyoshi exhibited in numerous group exhibitions, participated in many artist organizations, and was actively engaged in all aspects of the New York art world. A member of the Artists Equity Association and the American Artists’ Congress, he was the central figure among the Japanese artists who worked in the city between the world wars.

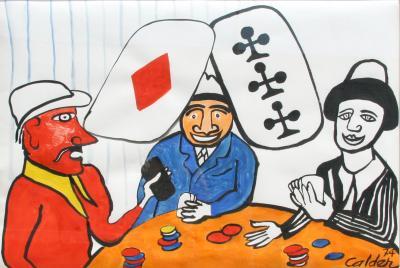

Over the decades, Kuniyoshi won significant prizes for his work, including first prize in the prestigious Carnegie International in 1944, having been selected for the exhibition on several previous occasions. When Look magazine polled sixty-eight art critics, museum directors, and curators across the United States in 1948 as to who were the best painters in the country, Kuniyoshi was voted third, after John Marin and Max Weber, and before Stuart Davis and Edward Hopper. Four years later, in 1952, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, along with Alexander Calder, Stuart Davis, and Edward Hopper.

Kuniyoshi’s life was closely linked to some of the major historical events of the twentieth century, and his art reveals a personal fusion of East and West. His work is subtle, sophisticated, and unique. The evolution of Kuniyoshi’s art from cheerful, idiosyncratic works of the 1920s, through his sensual and worldly paintings of the 1930s, to his richly troubling works of his last ten years is a deeply human story. His art doesn’t represent a particular style or movement; his figural imagery, humor, compelling themes, and powerful expression are uniquely his own.

In the 1920s, Kuniyoshi made highly original paintings that incorporated the influence of American folk art, a popular avant-garde enthusiasm at the time, and combined the imagery with elements from Japanese art, contemporary American painting, and European modernism (Fig. 2). After two extended visits to Paris in 1925 and 1928 he began painting from reality instead of from his memory and imagination. The resulting works were lushly brushed images of sensual women, some erotic, some melancholic, and complex personal still lifes, painted with refined, understated color (Fig. 3).

During his career, critics in the United States regularly claimed that there was something “Oriental” about Kuniyoshi’s painting, while the art public in Japan saw it as “European.” In fact, he merged the traditions of the East with the artistic concerns and viewpoints of the West in ways that were original and integrated, unlike many of his contemporaries who veered from one tradition to the other (Fig. 4). The Parisian modernism that inspired him was itself in part inspired by Japanese art. What set Kuniyoshi apart from his contemporaries was the sophisticated way that he drew from Japanese, European, American, and American folk art traditions and expressed them through a distinctive vision.

His career as an artist took place in the United States, but he was identified as Japanese because of his appearance, his manner of speech, and his citizenship. The years leading up to and through World War II were difficult times for Kuniyoshi. Despite his wish to become an American citizen, immigration law made it impossible for someone born in Japan to apply for citizenship until the early 1950s, just before his death. He was devoted to the United States and its democratic system, but also felt compassion for his native land. After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 he was classified an “enemy alien” by the U.S. government. Living on the East Coast, he was not confined to an internment camp, but he was subjected to prejudice and harassment. His art at this time took on a moodier aspect and he made violent drawings for the American propaganda effort (Fig. 5). In his postwar paintings he often rendered disillusioned subjects with paradoxically hot, brilliant color (Fig. 6).

For four years, from 1947 to 1951, Kuniyoshi dedicated a significant amount of his time and his talents to Artists Equity, an idealistic organization devoted to improving the lot of artists in the United States and based on the model of Actors’ Equity and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). He became increasingly involved with artists’ organizations, often as an officer. Consequently when a group of four hundred artists met at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1946 to create Artists Equity, he was elected its first president.

In 1947 two of Kuniyoshi’s paintings were included in the important Advancing American Art exhibition, a U.S. cultural diplomacy project that included such notable artists as Romare Bearden, Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper, Charles Sheeler, and Marsden Hartley. His painting Circus Girl Resting (Fig. 7), from 1925, was singled out for criticism, however, by no less than President Harry Truman; Kuniyoshi’s Japanese background continued to draw enmity even after World War II had ended.

Throughout his career, Kuniyoshi followed the Asian tradition that valued sumi ink drawings as finished paintings. He first developed his personal style of ink drawing in the 1920s, juxtaposing areas of white paper with eloquent fine lines and passages of thick ink that he scratched into for highlights. In some works, such as Remains of Lunch (Fig. 8), he revealed a mischievous sense of humor by depicting a pair of pears leaning against each other and by enclosing the lunch leftovers in a stomach-shaped form. Kuniyoshi’s career as an artist concluded with the profound and intense black ink drawings made in his last years, in counterpoint to his vividly colored paintings of the same time. With their physical handling and tragic subjects, his drawings paralleled the art being produced by the new generation of abstract expressionist artists (Fig. 9).

Kuniyoshi painted only about 350 works. The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (through August 30, 2015) features forty-one paintings and twenty-five ink drawings; drawn from public and private collections in the United States and Japan, they comprise the best of this immensely talented and individualistic artist’s production. The show will be the first major exhibition of the artist’s paintings in twenty-five years and will be of considerable interest to a new generation of art lovers in both countries.

This article is adapted from The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, by Tom Wolf, published in 2015 by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., in association with D Giles Ltd., London. Used by permission.

Joann Moser is deputy chief curator, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. She co-curated the exhibition with Tom Wolf, a leading Kuniyoshi scholar and professor of art history at Bard College.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.