The Effortless, Informal Magic of Mid-Century American Design

|

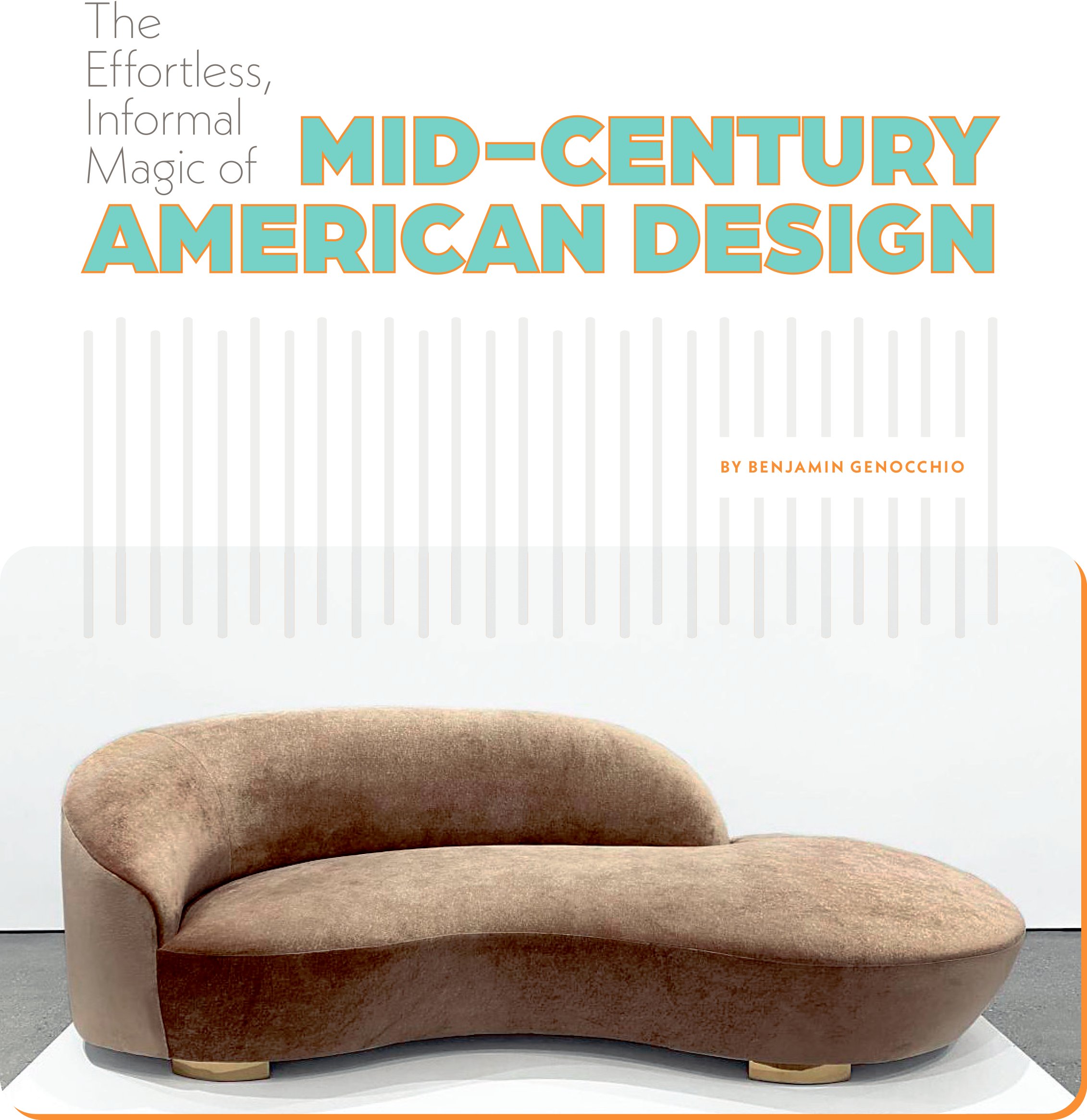

Vladimir Kagan “Cloud” Sofa. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery. |

American design in the first few decades of the second half of the twentieth century looked markedly different from design before World War II. That is because America changed: suburban areas were springing up nationwide to cater to a post-war baby boom and millions of new houses needed simple, practical, utilitarian and affordable furnishings. To meet the challenge, a new generation of designers sought inspiration from the latest industrial materials and mass manufacturing as well as Scandinavian modernism, a movement of designers, manufacturers and products that emerged in the 1950s in the Nordic nations and spread rapidly internationally.

| |

Rare Pair of Club Chairs by Paul László. Courtesy of Donzella. |

Scandinavian modernism placed an emphasis on organic materials such as wood and fabric, as well as a neutral palette, and sleek simplicity of furnishings. Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden may have been the origin of many of the ideas of what today we understand as mid-century modern design, abbreviated to MCM, but American designers had their own ideas about what the home should look like — the furniture they designed was efficient, versatile, comfortable, elegant yet informal. It was also replicable, as industrial designers and architects worked in collaboration with American furniture makers to create popular mass-producible designs.

| |

Marshmallow Sofa by George Nelson. Courtesy of Società Antiquaria. |

Mid-century modern design is characterized by extraordinary creativity and diversity — much like America itself, which in addition to a baby boom experienced a wave of immigration in the post-World War II period. George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Florence Knoll, Milo Baughman, Paul Evans, Harvey Probber, Edward Wormley, Paul McCobb and Adrian Pearsall are some of the biggest names in mid-century American design, and all of them were born and educated here in the US, but they also benefited from the expertise and guidance of many talented émigré designers including Tommi Parzinger, Karl Springer, Eero Saarinen, Vladimir Kagan, Paul László and T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings among many, many others.

To what, then, do we attribute the enduring legacy of mid-century American design?

| |

670 Lounge Chair and 671 Ottoman, designed by Charles and Ray Eames for Herman Miller. Courtesy of Open Air Modern. |

On a formal and conceptual level, the work of the best designs and designers of the period seems to transcend a dated look in favor of more ‘timeless’ design styles. On the one hand, the rigorous, functionalist legacy of the Bauhaus is extended through designs encompassing geometric, rectilinear forms and basic building blocks. On the other hand, the legacy of classicism and French Art Deco finds new interpretation via the sensuality of curved lines and organic forms (in reaction to the austerity of much geometric modern design), but also inspired by the versatility of new materials as well as production techniques. Shaped metal, plastic and wood led to innovative forms.

| |

Original Eames Fiberglass Shell Chairs by Herman Miller. Courtesy of Open Air Modern. |

Strong lines and geometric shapes define much of the work of George Nelson, who as a designer and then design director for Herman Miller from 1945–1972 promoted and popularized modernist design in America through his own designs as well as the concepts of others. His Home Office Desk Model #4658 for Herman Miller is a work of functional, versatile furniture from the 1950s combining leather-covered doors with shelves inside, perforated file holders along with tube chrome-plated steel hardware. Trained as an architect in the International Style, blocky geometric shapes and forms define his designs including his “Marshmallow” sofa, from 1956, made of a black lacquered steel frame with circular cushions upholstered in colored faux leathers.

Cecilia Paccagnella from Società Antiquaria in Turin says the Marshmallow sofa best embodies the “atomic design” style characteristic of George Nelson, who, she says, “often liked to divide furniture into distinctly separate, brightly colored parts with a strong playful tone.” It is an informal, iconic design pointing to an emerging Pop sensibility, she says. “As it was first designed in 1956, the Marshmallow sofa can be seen as a precursor of the design inspired by the Pop Art movement that came later. Due to its unique shape and colors, it is not a conventional sofa and therefore always draws attention to itself and, in any room, it becomes a catalyst for conversation.”

|

T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings “Cloud” Coffee Table for Widdicomb. Courtesy of Original in Berlin. |

| |

T. H. Robsjohn Gibbings “Saridis” Walnut Table, Bronze Claw Base, ca. 1960. Courtesy of Lance Thompson Inc. |

Many designs produced in America in the first few decades after World War II are iconic, an overused word, but in this case, appropriate. Designs by Eero Saarinen and Warren Platner, and of course Florence Knoll herself have been in production for decades at Knoll. Meanwhile, Herman Miller, the most popularized American furniture manufacturer of the last century (today merged with Knoll to become Miller Knoll Inc), continues to produce designs by Charles and Ray Eames as well as George Nelson. Thayer Coggin continues as the exclusive maker of Milo Baughman's mid-century designs in streamlined shapes, including the luxurious drum coffee table or the “Tilt” swivel chairs and “Scoop” lounge chairs which he is best known for.

Among famous or iconic designs from the period, Florence Knoll’s work deserves to be singled out. Her reinterpretation of International Style architectural influences with an emphasis on geometric forms resulted in linear designs of steel, walnut, marble or chrome credenzas that redefined interiors, along with geometric sofas and chairs for home and office. Although they were mass-produced, vintage examples are now collector’s items. The same goes for the work of legendary Finnish-American architect, designer and teacher Saarinen, though he took an opposite approach to Knoll in terms of design sensibility — for example, his organic “Tulip” table and chairs, and the “Womb Chair,” not to mention architectural gems such as the St. Louis Arch.

|

Tastes and the market evolved through the second half of the 20th century and not surprisingly, designers worked within and between styles. Adrian Pearsall produced a variety of popular furniture designs, ranging from the hard-edged walnut “Boomerang” sofa for Craft Associates to angular, organic lamps and lounge chairs in walnut, including the Model 2249-C Walnut Lounge Chair for Craft Associates, the company he founded in 1952 with his brother in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., to create affordable functional design. It was so successful they sold the firm to Lane Furniture. Scandinavian mid-century furniture was his core inspiration and wood, especially walnut, is the base material for his most iconic pieces such as his own “Gondola” sofa.

|

Brutalist set of six Dining Chairs in Latte Bouclé by Adrian Pearsall, ca. 1970. Courtesy of Interior Motives |

|  | |

| Left: “Unicorn” Side Table by Vladimir Kagan, ca. 1960s. Courtesy of Peter Blake Gallery. Right: Milo Baughman for Thayer Coggin Scoop Lounge / Armchair. Courtesy of Newel. | ||

| |

Pentagonal Janus Coffee Table with Natzler Tiles by Edward Wormley for Dunbar. Courtesy of Machine Age. |

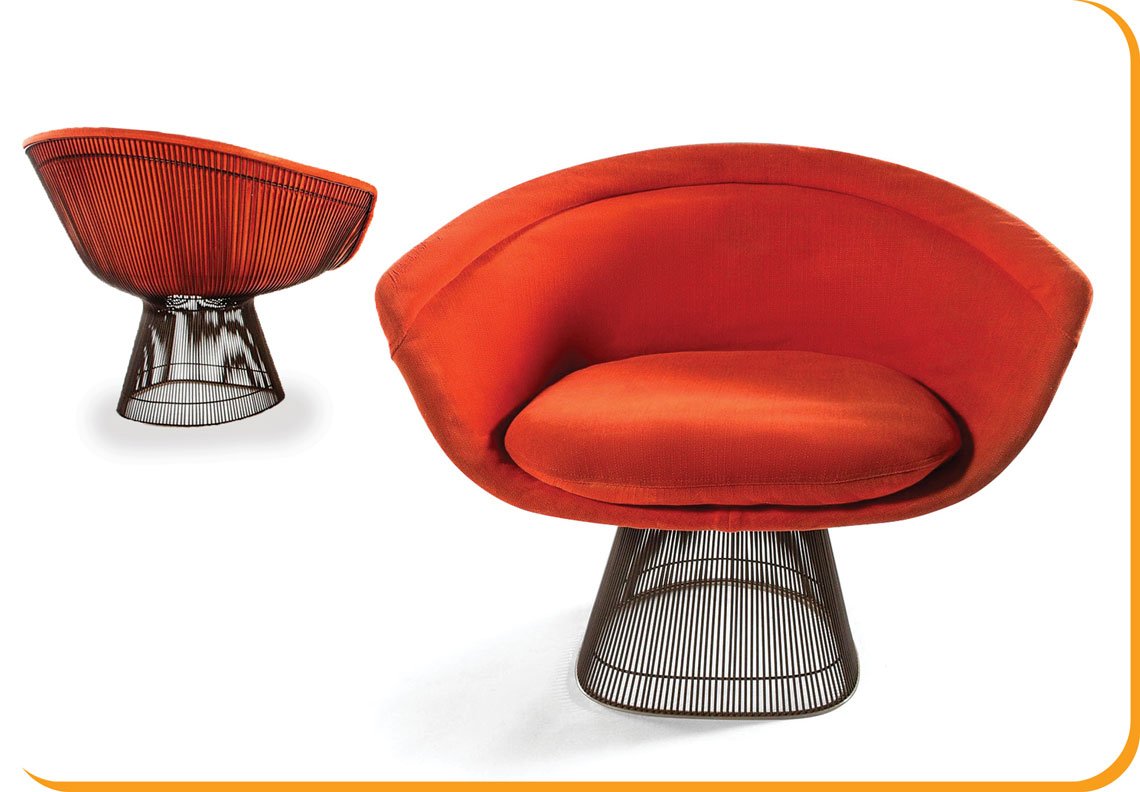

Plastics, fiberglass, malleable woods and metals enabled new shapes and forms for furniture in the 1950s. Platner and Bertoia (who worked in the Eames’ offices in California in the 1940s) exploited this opportunity to create some of the most popular and enduring mid-century designs. First offered by Knoll in 1966, the Platner Wire Lounge Chair has become a classic, along with a related range of tables and chairs in sculptured wire. The Diamond Chairs by Bertoia, also made by Knoll, have found similar public favor along with several equally adventurous organic designs by the Eames team for Herman Miller — who hasn’t sat in an Eames fiberglass Shell Chair? Experimentation with plywood for chairs led to the Eames’s 670 Lounge Chair and 671 Ottoman, commissioned by Herman Miller and released in 1956, and today one of the world’s most famous chairs.

Modular furniture was also one of the great innovations of the period. Probber is often credited with the ‘invention’ of the sectional, modular sofa, in the 1940s, a design that influenced other mid-century designers. His designs are clean-lined and austere, and yet there is often a luxe, elegant approach to the defining geometric and recto-linear modernism of the period with a preference for comfort and ease. Probber favored fine craftsmanship and the use of high-quality materials including rare woods, leathers and fabrics as well as expensive finishes like polished lacquer. His “Sectional Sofa in Black Leather with Mahogany Legs,” from the 1950s, illustrates nicely the way modular furniture can be elegantly simple yet sumptuously beautiful.

|

Edward Wormley La Gondola Sofa Model 5719, for Dunbar, ca. 1950s. Courtesy of circa20c. |

|

Florence Knoll executive office rosewood cabinet. Courtesy of Collage 20th Century Classics. |

| |

Lounge Chair by Warren Platner for Knoll. Courtesy of ABT Modern. |

Evan Lobel from Lobel Modern in New York has long dealt in Probber’s works which he greatly admires. “Harvey Probber was a seminal figure in American 20th-century modernist furniture design. He was the inventor of sectional seating for sofas, which he named Nuclear Seating. His elastic sling chair and Nuclear upholstered groups were chosen for MoMA’s Good Design exhibition in 1951. He was also one of the only designers who owned his manufacturing facility, so he personally oversaw the craftsmen making his designs.

‘Timeless glamour,’ a term applied to Probber’s designs, is something Karl Springer took to a new height with his use of restrained modern forms decorated with precision and fine craftsmanship, including mosaic surfaces with tessellated tiles, inlaid-wood veneers, faux finishes, exotic reptile skins and granite. “I am drawn to a designer that does work with meticulous craftsmanship and the finest materials,” says Lobel, who also is an expert on Springer, “it just pulls me in. I want to know, how did he do this? Before Springer brought goatskin to market in the 1960s no one else had done it — the last person was probably Jean-Michel Frank. More advanced chemical coatings were developed, so goatskin could be covered in lacquer, making it durable.”

| |

Womb Chair and Ottoman by Eero Saarinen for Knoll. Courtesy of Machine Age. |

Springer’s story is somewhat different from that of other period designers, as he began his career creating small, decorative objects covered in fine leathers, drawing upon skills developed in his previous career as a bookbinder. “He was really more of a hands-on artist in my opinion,” Lobel says, “pretty much everything that he created was custom made and is unique.” Lobel points to a pair of “Onassis Bar Stools” in lacquered goatskin made with hand-stitched black leather seats and brass foot rails from the 1980s. “His exacting attention to detail along with a wonderful sense of scale and proportion makes his work impressive.” Springer’s metal and glass “Freeform Tables” in various finishes are today American design icons.

| |

Pair of Karl Springer Goatskin Onassis Bar Stools 1980s. Courtesy of Lobel Modern, Inc. |

Like Springer, Wormley and Robsjohn-Gibbings are widely considered to be among the most important designers of the period. But unlike Springer, both benefited from extensive collaborations with larger furniture manufacturers — in the case of Wormley, three decades of designs for the Dunbar Furniture Co. in Berne, Indiana, set the standard for elegant modern interior furnishings, as evident in his pentagonal “Janus” coffee tables decorated with Otto Natzler tiles or the walnut, cane, tan leather “Janus” armchair. His “La Gondola Sofa” model 5719 is a graceful design and one of the period’s most iconic — and most imitated — furniture items.

“The genius of Edward Wormley is on full display with the Gondola sofa, which is one of our favorite Dunbar pieces. The gracefulness of this sofa takes your breath away and is a true design classic — a beauty,” says Jean Nelson of circa20c in Dallas, Tx. “The partnership of Edward Wormley and Dunbar Furniture Co. resulted in some of the most beautiful, timeless and well-crafted furniture in the 20th century. Wormley was a traditionalist at heart who appreciated the fine artisan craftsmanship of the past. But he also understood the modern-day design trends of the 20th century and updated, reimagined and reinterpreted furniture to create timeless, elegant, functional, innovative and forever classic design.”

T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings moved to America from England in the late 1930s and, like Wormley, was devoted to elegant, spare forms and classical principles of European interior design. He began his career as an antique dealer in London and later with his shop on Madison Avenue. Dealer Lance Thompson, among others, retains admiration for Robsjohn-Gibbings, pointing to how he was able to update the past for the present and make it his own. “Following in the footsteps of Palladianism and English architects Inigo Jones (17th c.) and William Kent (18th c.), both champions of Andrea Palladio, a 16th-century Venetian architect, he infused Roman and Greek principles of symmetry, proportion and restraint into American Modernism and design, creating a fresh departure from mid-century Europe.”

|

Harvey Probber Cubo Sectional Sofa. Courtesy of Modern Drama. |

| |

1950s Harvey Probber Dining Chairs. Courtesy of Flavor. |

His designs found immediate favor with the rich and famous — he designed homes for Elizabeth Arden, Alfred Knopf, Doris Duke, and others. His inspiration from classical, especially Greek furniture is visible right throughout his career in his daybeds, sofas, chairs and stools, says Thompson, but is, he says, particularly visible in “examples made by Saridis of Athens with whom Gibbings collaborated while living in Greece in the 1960s, often using [old] pediment, frieze motifs, and lion’s claw feet.” One good example of this is his ‘Saridis’ walnut table, with bronzed claw base, from circa 1960, produced with Saridis. The tripod table form goes back to ancient Egypt, but in this case, is updated with a simplified wooden top to highlight the decorative legs. Though classically influenced, Robsjohn-Gibbings’ designs are always informal and livable.

Robsjohn-Gibbings also produced innovative designs such as the organically-shaped “Cloud” coffee table by Widdicomb. From 1943 to 1956, Robsjohn-Gibbings worked as a product designer for Widdicomb in Grand Rapids, Mich., where he designed many of his most popular pieces. “The Cloud table, which was first introduced in 1948, is a sculptural piece with a distinctive curvilinear shape and seemingly floating top,” says Lisa Staub, from Original in Berlin. “It is made from solid walnut and features a thick, oval-shaped top that is supported by a series of brass legs that taper down to pointed feet. The legs are arranged in a triangular pattern, giving a sense of movement and fluidity. The effect is one of lightness and grace, as if the table is floating on air.”

Staub sees the Cloud coffee table as a significant departure from the more “angular, rectilinear designs that were popular in the mid-century modern period,” something Robsjohn-Gibbings was to use to great effect for his biomorphic “Mesa” coffee table, one of the most coveted, expensive pieces of mid-century American design. Inspired by the American Southwest, the terraced, free-flowing form echoes the flat, wind- and water-eroded table-like high desert mountain plains of Arizona. Original Mesa coffee tables (usually made of walnut) from the early 1950s have sold for almost $400,000 at recent auctions. The design is another American classic.

| |

Top: “Janus” Lounge Armchair by Edward Wormley. Courtesy of Newel. Center: Free Form Coffee Table in Brass and Granite by Karl Springer. Courtesy of soyun k. Bottom: Adrian Pearsall Model 2249-C Walnut Lounge Chair. Courtesy of Danish Modern LA. |

The story of mid-century American design includes more than just designers working for larger furniture brands and manufacturers creating mass-produced products, even if finished by hand. The American studio furniture movement is made up of individual makers doing their own thing, creating unique sculptural objects. Examples include, for those working with metal, Paul Evans (who had a parallel career from 1964–1981 as a designer for manufacturer Directional Furniture), Silas Seandel, and Philip and Kelvin LaVerne along with a range of talented studio furniture makers who favored wood, among them George Nakashima, Sam Maloof, and Wendell Castle.

Then there is Vladimir Kagan whose work “traversed boundaries of art and functional design,” as dealer Peter Blake summarizes. Kagan’s organic, sinuously curved designs were often inspired by nature and the human body as well as modern art and artists, says Margaret Kim from soyun k. gallery. “He explored sculptural forms derived from natural elements and the human anatomy with their organic and sensual lines.” During the 1950s, Kagan integrated these ideals and concepts in his revolutionary designs for chairs and sofas, often incorporating innovations in spring systems. “Not only was the seating structured to be comfortable, but the clean sculptural lines were designed to be aesthetically pleasing viewed from all angles,” Kim adds.

Kagan’s “Unicorn” series was one of his favorite and most popular designs, inspired, Kim explains, by the work of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi, most notably, Brancusi's sleek bronze monolithic object, “Bird in Space,” which he had seen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “It was used first for the base of tables in wood in 1957, and later cast in bronze and aluminum,” Kim says. “A rare and possibly unique Unicorn stool is a fine example of this iconic series, which captures Kagan’s creative interpretation of this delicate balance between representative and abstract expressions. The delicate contoured seat of this stool is mounted on an organic sculptural cast and polished aluminum base mimicking its triangular form.”

There were regional American variants of mid-century American design as well, dealer Paul Donzella is quick to point out. Not everything was happening in New York or Chicago. Donzella got his start in New York in the design business as an MCM dealer, with a passion for Robsjohn-Gibbings, who he still follows in the market. But he also discovered and admired the works of Paul Laszlo, a Hungarian architect and immigrant to California who made furniture and sculpture in Los Angeles as well as becoming a popular interior designer for homes and stores. “Laszlo was a pioneering force in the evolution of California Modernism,” Donzella says. “He employed rigid European lines with plusher, more comfortable proportions. Adding a strong sense of color and texture, he created a very unique flavor that was distinctly Los Angeles.”

Milo Baughman’s Iconic Tilt/Swivel chairs. Courtesy of circa20c. |

Like the work of other MCM designers, Laszlo’s pieces are increasingly collectible and desired in the market. So what is driving demand? Marietta Klase from Newel, a prominent dealer in the material, says it is likely to do with today’s more informal lifestyle.

“I think contemporary lifestyles are incompatible with fussy or overly complicated, formal furniture. The American mid-century design philosophy still resonates with current collectors seeking comfort and versatility. Many of the industrial designers from that period became renowned celebrities in their own right and their designs are viewed as investment classics. These pieces from the 50s and 60s are so playful to mix and match with other antiques and bespoke furniture to create layered eclecticism within a space.”