The Eyes Have It

Exquisite in craftsmanship, unique in detail, and few in number, “lover’s eyes”—as they are popularly known today—are hand-painted miniature portraits of individual human eyes presented in an astonishing array of settings, both decorative and functional. Among the many objects housing these miniatures are lavish rings, brooches, necklaces, and boxes. From February 7 to June 10, 2012, the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama, will present The Look of Love: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection, the first major exhibition of these enigmatic works of art.

Struck by the splendor of a circa-1790 diamond and blue enamel ring featuring a lover’s eye (Fig. 1), Nan and David Skier of Birmingham, Alabama, began their eye miniature collection with this solitary purchase at an antique show in 1993. With fewer than a thousand lover’s eyes thought to exist, over the past two decades the Skiers have quietly built the largest collection of these miniatures in the world, now at one hundred examples. “These rarities are at once works of art, precious jewels, and fragments of history. How poignant it is that each eye represents an actual person and an actual story of a long-ago love or bereavement, now lost to the passage of time,” says Mrs. Skier.

|

| Fig. 1: Blue enamel, diamond, and pearl ring, ca. 1790. 3/4 x 1-1/4 x 7/8 inches. |

Although a handful of Continental examples are known, the majority of these unusual objects were produced in England during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They are typically painted in watercolor on ivory, though sometimes card or vellum was used. Evidence suggests that the phenomenon began in France, but the popularity of lover’s eyes, if not their origin, can be traced to England, in a scandalous love story of royal proportions. In 1784, the twenty-one-year-old Prince of Wales (later George IV, 1762–1830) became smitten with Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert (1756–1831), a twice-widowed Catholic six years his senior. The prince doggedly pursued Mrs. Fitzherbert, declaring his intentions to wed. However, under the Royal Marriage Act, the prince could not marry without his father’s consent until the age of twenty-five, and it was a foregone conclusion that King George III would frown upon the heir to the throne marrying a Catholic widow. Mrs. Fitzherbert initially rebuffed the prince’s advances, but after he staged a suicide attempt to demonstrate his despair, she relented and accepted his proposal. The following day, realizing the haste of her decision, she fled to the Continent, remaining there for more than a year. She hoped that her absence would quell the prince’s feelings, but true to the old adage, it only made his heart grow fonder.

On November 3, 1785, the prince wrote to Mrs. Fitzherbert with a second proposal of marriage. Instead of an engagement ring, he sent her a picture of his own eye, painted by the miniaturist Richard Cosway (1742–1821), among the most celebrated artists of the day. The prince closed his letter with the words, “P.S. I send you a Parcel…and I send you at the same time an Eye, if you have not totally forgotten the whole countenance. I think the likeness will strike you.” It is unknown whether it was the letter or the intimate token of love that stirred Mrs. Fitzherbert’s feelings, but shortly thereafter, she returned to England and married the prince in a secret ceremony on December 15, 1785. Not long after their clandestine nuptials, Mrs. Fitzherbert (as she preferred to remain) commissioned Cosway to paint a miniature of her own eye for the prince. The Prince of Wales’ token of affection inspired an aristocratic fad for exchanging eye portraits mounted in a wide variety of settings that lasted for the next few decades.

|

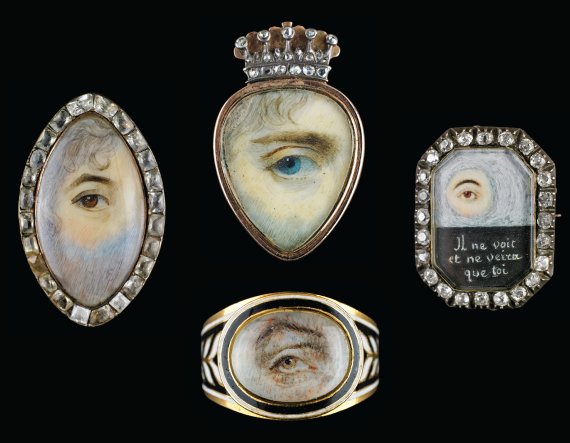

| CLOCKWISE FROM FAR LEFT Fig. 2: George Engleheart (British, 1750-1829), Eye set in yellow gold navette-shaped ring surrounded by paste stones, ca. 1790. 1-1/4 x 3/8 x 1 inches. Fig. 3: Thomas Richmond the Elder (British, 1771-1837), attributed. Gold ring with heart-shaped miniature surmounted by gold and diamond crown, ca. 1835. 1-3⁄16 x 3/4 x 1-3⁄16 inches. Fig. 5: Octagonal silver and gold brooch surrounded by diamonds, ca. 1800. 1-3⁄16 x 15⁄16 x 1/4 inches. Fig. 4: Yellow gold ring with black and white enamel decoration, 1808. 1/2 x 5/8 x 13⁄16 inches. |

Many of the leading miniaturists of the late Georgian period painted lover’s eyes, but only rarely can pieces be firmly attributed to a specific hand. A delicate brown eye set in a ring is signed in the lower right with a cursive letter “E,” the signature of George Engleheart (1750–1829), miniaturist to George III and a rival of Cosway (Fig. 2). Another exquisitely rendered eye, set in a ring crested with an earl’s coronet (Fig. 3), is believed to be the work of Thomas Richmond the Elder (1771–1837), who briefly studied with Engleheart. Nearly as rare are pieces in which the identity of the sitter is known. One notable example is a black and white enamel mourning ring embellished with a wizened hazel eye (Fig. 4). An inscription on the interior of the band tells us that this is one A. M. Bennett who died on February 12, 1808, at the age of sixty-four. Genealogical research has revealed that that the individual commemorated is Anna Maria Bennett (1745–1808), a well-known novelist, author of such titles as Agnes De-Courci (1789) and Vicissitudes Abroad (1806).

It is not surprising that the identity of so few subjects is known since that was really the point of these intimate portraits. Clandestine lovers could exchange such miniatures without fear of discovery, since one’s eye would—in theory—only be recognized by persons with the utmost familiarity. This notion of the intimacy of the gaze is hinted at in a diamond-encrusted brooch of around 1800. Beneath a brown eye surrounded by clouds is a French inscription that translates to “It does not see me, it only sees you” (Fig 5).

|

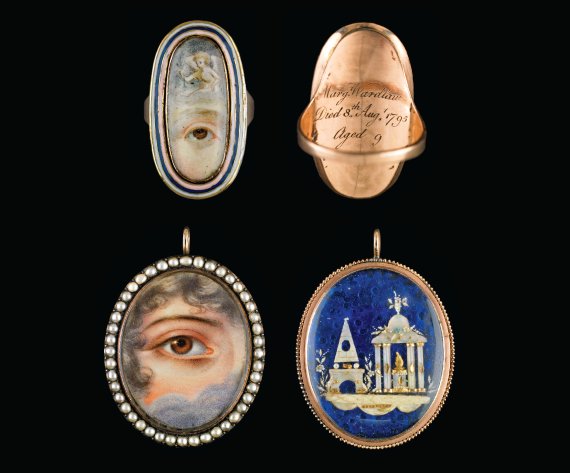

| CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT Fig. 6: Gold oval ring with white, blue, and pink enamel, 1795. 1-3⁄16 x 11⁄16 x 13⁄16 inches. Fig. 7: Reverse side of ring shown in fig. 6. Fig. 8: Gold oval pendant surrounded by seed pearls. Mourning motifs in mother-of-pearl, ivory and gold against blue glass background, ca. 1830. 1-3/8 (with hanger) x 1-3/8 x 3/4 inches. Fig. 9: Reverse side of pendant shown in fig. 8. |

If the gift or exchange of lover’s eyes was initially confined to romantic gestures, the phenomenon quickly spread to the family circle, and several instances of entire families having their eyes taken are recorded. Many pieces of lover’s eye jewelry also served a memorial function, either confirmed by the presence of an inscription or suggested by clouds signifying the passage into heaven. A particularly good example of this is a gold oval ring with white, blue, and pink enamel, dating from 1795 (Figs. 6 and 7). A brown right eye with a heavy lid is depicted below an angel holding a palm frond hovering above a cluster of clouds. The inscription on the reverse reveals that the ring is a memorial to Margaret Wardlaw, who died at the age of nine on August 8, 1795. Another striking example is an oval pendant of around 1830 (Figs. 8 and 9). The painstakingly rendered brown eye is surrounded by seed pearls, often used in memorial jewelry to symbolize tears. The reverse side of the pendant is decorated with various mourning motifs, including a pyramidal tombstone and a mausoleum housing an eternal flame, fashioned from mother-of-pearl, ivory, and gold against a blue glass background.

|

| LEFT TO RIGHT Fig. 10: Rose gold oval brooch surrounded by seed pearls with Prince of Wales’s Feathers, undated. 1 x 1-1/4 x 1/4 inches. Fig. 11: Reverse of brooch shown in fig. 10. |

|

| LEFT TO RIGHT Fig. 13: Reverse of gold ring shown in fig. 12. Fig. 12: Heart-shaped gold ring with Hessonite garnet surround; sepia and embroidered hairwork image on reverse, ca. 1790. 15⁄16 x 5/8 x 7/8 inches. |

Because lover’s eye jewelry falls under the larger category of “sentimental jewelry,” it is common to find pieces that combine eye miniatures with hairwork. Typically, small compartments on the reverse of the piece known as “boxes” contained simple plaited hairwork, but more elaborate examples exist, evident in a circa-1830 rose gold brooch containing hair fashioned as the Prince of Wales’ feathers, the heraldic badge of the heir apparent (Figs. 10 and 11). An even more intricate example can be found on the reverse of a circa-1790 Hessonite garnet ring, which is decorated with a sepia and embroidered hairwork image depicting interlocking hearts in front of an oak, the tree symbolizing the strength and endurance of love (Figs. 12 and 13).

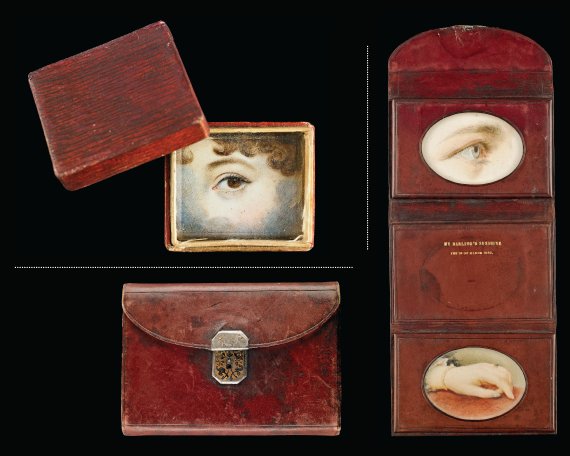

Some lover’s eyes fall outside the category of jewelry altogether. One such example is a so-called “memory box,” a small paper box containing a beautifully painted brown eye under glass (Fig. 14). Such an object was presumably carried on one’s person and opened for viewing when struck by a pang of love or loss. A similar object, and among the latest examples in the Skier collection, is a dark-red leather wallet that opens to reveal portraits of an eye and a hand, and is stamped with the inscription, “MY DARLING’S SUNSHINE / THE 26 OF MARCH 1882” (Fig. 15). The inscription might allude to a yet to be identified literary source or it could refer generally to the idea of eyes radiating light and warmth like the sun.

|

| UPPER LEFT: Fig. 14: So-called “memory box” made of embossed and painted paper containing eye miniature, ca. 1830. 1-1/4 x 1-1/4 x 3/8 inches. BOTTOM AND RIGHT: Fig. 15: Dark-red leather wallet with gold decorated engine turned clasp containing eye and hand miniatures, stamped with the inscription, “MY DARLING’S SUNSHINE/THE 26 OF MARCH 1882,” 1882. Case (open): 3-7/8 x 9-5/8 x 1/4 inches. |

The popularity of lover’s eyes had already waned by the time of Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1837, but the practice never died out entirely. In the first decades of her reign, Victoria herself commissioned several eyes from court miniaturist Sir William Ross (1794–1860), and examples dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are known. In recent years, lover’s eyes have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity among contemporary miniaturists. The New York artist Elizabeth Berdann has painted eyes on copper, vintage ivory, and mammoth ivory. Mammoth ivory—free from the restrictions of elephant ivory—is also the choice of Thomas Sully III, a North Carolina miniaturist who is the great-great-great grandson of the eminent Philadelphia portraitist of the same name.

Graham C. Boettcher is the William Cary Hulsey Curator of American Art, Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama.

All images courtesy the Skier Collection. Photography by M. Sean Pathasema.

This article was originally published in the 12th Anniversary (2012) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|