The Glory Days of Ohio Pottery and Glass, 1860–1945

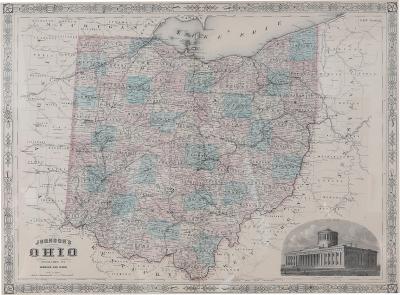

In Ohio’s early years, clay deposits were discovered along a number of riverbanks and small-scale stoneware potteries sprang up to meet the utilitarian demands of a growing population. These potteries later took advantage of the state’s excellent location and the various transport routes—the railroads, the canals, the Great Lakes, and the rivers—to export to growing urban centers. High-quality sandstone with the necessary levels of silica to be pounded down for glass production was also discovered and glass factories cropped up as well, although the deposits would confine glass production, at least in the earliest years, to the Zanesville, Kent, and Mantua areas. Larger-scale pottery operations would take root in the southeastern part of the state, around the Akron area, and in Cincinnati, all areas where clay and water access were abundant. Wood and coal were also necessary in vast quantities for firing the kilns and furnaces; later, with the coming of the Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914), the scale of manufacture increased and new technology was implemented in a number of ways, at which point the potteries and glass factories in the eastern and southeastern portions of the state successfully boosted production in part through the benefits of firing with natural gas.

Curtis Houghton became an Ohioan like many before him, following the westward movement from New England. Houghton, who might have worked previously as a potter in Bennington, Vermont, founded his own pottery in Dalton, Ohio, in 1842. It was later passed to his son Edwin and then to his grandson Eugene, who was at the helm when the pottery operations began to shift from the primarily utilitarian wares of the nineteenth century to art pottery that included a wide range of new glazes and forms.

Among them was the spaniel doorstop or chimney ornament (Fig. 1). These spaniels, more properly known as Cavalier King Charles spaniels, were first produced in Victorian England by Staffordshire potteries. Produced in vast quantities, they were widely available and affordable, adorning the mantels of the British middle classes for decades, and naturally also making their way to America, where they were reinterpreted by American potters, eager to manufacture their own versions. Nowhere, it seems, were they more enthusiastically embraced than in Ohio, where potteries produced them in a fascinatingly wide variety in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Eugene Houghton surely saw the imported versions, but he also was certainly aware of those produced by Ohio potteries, as his company’s version owes a great deal to the spaniels manufactured in East Liverpool, Ohio, a generation early, where they were typically produced with a Rockingham glaze.

East Liverpool was, during the second half of the nineteenth century, one of the most productive pottery centers in the Ohio River Valley. The city, aware of the local advantages to potters, incentivized the process, offering grants for the construction of potteries. The future of the industry changed when, in 1872, East Liverpool awarded such funds to Homer and Shakespeare Laughlin. Just four years later, the Laughlin brothers won an award for their white ware, and a year later, Homer bought his brother’s share and renamed the company Homer Laughlin (becoming Homer Laughlin China Company in 1896).

The company’s rise to success was every bit as meteoric as it seems, largely underwritten by the demand from hotels and other institutions for copious amounts of the famous Laughlin white wares, which allowed Laughlin the freedom to experiment with projects like creating a true porcelain. The company created a porcelain in 1886 and continued to tweak the results, producing a pâte-sur-pâte (“paste on paste”) porcelain (Fig. 2). Laughlin’s source of inspiration and information for the technique, which was developed by Marc-Louis Solon, is unknown, but it involves creating relief decoration by painting successive layers of slip rather than using a spring mold. While laborious and tedious, the process assures that porcelain retains its coveted translucence. Both the traditional porcelain and pâte-sur-pâte were short-lived at Homer Laughlin, as the lines were abandoned in 1896 in favor of a focus on earthenwares. In the coming years, the company would continue to grow, establishing a large factory complex across the Ohio River in West Virginia and gaining popularity with the 1936 introduction of their colorful Fiesta dinnerware line.

Laughlin’s company was not the only one to find success in color. August H. Heisey, a German-born Pittsburgh glassmaker who married into the Duncan family of the Ripley Glass Company, founded his own glass company in 1896, finding affordable labor and abundant natural gas in Newark, Ohio. The Heisey Company’s specialty was finding the perfect balance between quality and affordability. Their pressed glass was of such incredibly high quality that pieces like their classically inspired punch bowl in flamingo pink (Fig. 3) could pass for the more expensive Gilded Age cut-glass option.

In a sea of volume, strategy was necessary to stay afloat. Houghton kept abreast of trends, Laughlin had their white wares to support them, Heisey flawlessly mimicked luxury, and the Cambridge Glass Company, founded in 1873 in Cambridge, Ohio, favored innovation through the production of a wide range of colors.

A steady flow of new product lines was the linchpin for the Cambridge Glass Company when it came to attracting new customers. Starting in 1922 and continuing until 1924, when Cambridge significantly curtailed their production of opaque glass in favor of transparent, they debuted new opaque colors each year. The Primrose Yellow console set (Fig. 4) was rolled out in 1923, along with Helio, a medium purple, and Carrera, a bright white, and Primrose Yellow is one of seven Cambridge colors that included uranium. In 1937, two years before he purchased the controlling interest in the company from his father-in-law, Cambridge Glass’s president, Wilbur Orme, who developed a number of the company’s designs and colors, pioneered Cambridge’s Table Architecture pattern (Fig. 5) that allowed a table to be set in a variety of sleek, modern ways with a selection of candle blocks, stepped candleholders, and console bowls.

Some companies found the constant strain of innovating too much, and it was simpler for them to return to the reliability of utilitarian materials. Such was the case with J. B. Owens Pottery (Fig. 6), which began producing art pottery in 1896 with Utopian, its version of Rookwood’s standard glaze, and produced about four dozen lines of pottery over the next decade. By 1907, however, the tile business was more profitable and the art pottery aspect of the business was abandoned when the company became the J. B. Owens Floor and Wall Tile Company.

Other companies succeeded with one artistic angle that had wide appeal. Cincinnati’s Rookwood Pottery had dozens of artists, styles, and lines, but the Rookwood pieces that are most beloved are typically those in their vellum glaze (Fig. 7). Vellum was officially premiered in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, where it was wildly popular, won the grand prize, and was feted as a valuable advancement in the field. At Rookwood, vellum was used with a number of decorating styles—the most popular being Scenic Vellum (landscapes) and Venetian Vellum (scenes of Venice)—until 1948, when E.T. Hurley, a star in the Cincinnati artistic firmament, retired. Hurley was an accomplished artist. He not only decorated for Rookwood, he was also a skilled printmaker and author who illustrated his own works. When he left Rookwood, it was quietly agreed that vellum’s most successful artist had retired and the glaze should as well.

Rookwood achieved greatness with pure artistic talent, which was also the case for the Cowan Pottery, when, in 1928, they hired Waylande Gregory, an immensely talented twenty-three-year-old sculptor. Gregory worked at Cowan for three years, until they closed in 1931, but during his tenure he created some of the most iconic Art Deco work in Cowan’s portfolio. Many of Gregory’s finest pieces were table-top sculpture, like the Dawn console set (Fig. 8), which consists of a central flower figure flanked by a pair of three-light candelabra, all in a silver and black glaze. Talent, however, was not enough to save the Cowan Pottery. The pottery, which was producing 175,000 pieces per year in 1928, was dealt a mortal blow by the Great Depression in the fall of 1929, and within a year it was in receivership.

Many of the potteries and glass factories that struggled on through the Depression were knocked back again with the United States’ entry into World War II. Ohio’s raw materials were requisitioned for the war effort (a move that particularly hurt potteries as they lost the various metallic compounds used in glazes), and its factories were retooled for everything from munitions to communications equipment to airplane parts. In the postwar landscape, Ohio’s potteries and glass factories met with new styles, new competition, and new business models, with consolidation either buying up or overpowering the smaller operations that had once dotted the landscape, particularly in southeastern Ohio.

In the antiques world, where value is most often driven by scarcity, wares by names like Heisey, Cambridge, and even Rookwood are anything but rare. And while all these companies have their versions of Jazz Bowls and Hurley Scenic Vellums, the same volume that makes their work ubiquitous also reveals how extraordinary that work was. These companies and their wares are quintessentially American, and even their most commonplace pieces embody our very best: industry, innovation, and independence.

These works are in the exhibition A Tradition of Progress: Ohio Decorative Arts 1860–1945, which is on view through May 17, 2015, at the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio in Lancaster, Ohio.

Andrew Richmond is a vice president of Garth’s Auctions, Delaware, Ohio, and a curator of A Tradition of Progress: Ohio Decorative Arts 1860–1945. Hollie Davis is a freelance writer and senior editor at Prices4Antiques.com.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.