The Mysterious Art of Elihu Vedder

|

Gallery for Mysterious, Marvelous, Malevolent: The Art of Elihu Vedder, Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. |

The exhibition Mysterious, Marvelous, Malevolent: The Art of Elihu Vedder was the first of three exhibitions created under the auspices of the Art Bridges + Terra Foundation Initiative.1 Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute is just one of four regional museums selected by the foundation to partner with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In this five-year project, the MFA shares collections and resources that will help Munson-Williams create a series of American art exhibitions that support our mission of becoming more inclusive, equitable, and diverse. The outstanding works of art we select from the MFA enable the museum to further engage the local communities that make the Mohawk Valley of New York so unique.

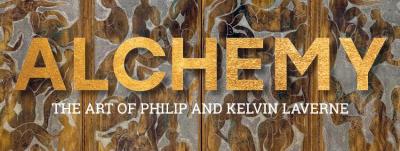

For Munson-Williams’ first exhibition, I chose to borrow Elihu Vedder’s The Questioner of the Sphinx. Ever since its first public appearance in 1863, Vedder’s painting has been a mystery. Elihu Vedder (1836–1923) was an American symbolist painter, book illustrator, and poet. Born in New York City and best known for his illustrations for the edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam published by Houghton Mifflin in 1884. Vedder trained in Manhattan then in Paris before completing his studies in Florence, Italy, where he was strongly influenced by Italian Renaissance work and the Italian landscape. He returned to New York City in 1861, at the outset of the American Civil War (1861–1865), where his work underwent a radical shift to increasingly mysterious and visionary paintings, drawings, and book illustrations.

Along with the The Questioner of the Sphinx, the exhibition presented almost thirty oil paintings, drawings, and illustrated books, including art from private collections that had never before been shown publicly. These works enabled viewers to explore Vedder’s journey into the realm of vision, nightmare, and dream. And, to consider if Vedder may have used ancient myths and legends of the monstrous, the terrible, the fantastic, and the unknown to negotiate the horror, destruction, and alienation engendered by the national crisis of the American Civil War. At the end of the Civil War, Vedder left America to live in Italy.

|

|

Fig. 1: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Questioner of the Sphinx, 1863. Oil on canvas, 36 x 42 inches. Bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer (06.2430). Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. © 2019, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. |

|

Exhibited in the middle of the American Civil War, this work introduced Vedder’s preoccupation with the riddle of existence to an unstable American public. With this and later works, Vedder used mythology and allegory as a means for Americans to explore the mysteries of life and death in an era of spiritual unrest and national distress. The unknown outcome of the war, the horrifying annihilation of men on the battlefield, women performing men’s roles on the home front, and the potential emancipation of four million slaves, threw the future of the United States into question. Like the wanderer in Vedder’s painting, America was longing for answers. In this eerie nightscape, Vedder paints a weather-beaten wanderer with his ear pressed against the stony lips of the Sphinx. The background reveals the wanderer’s circuitous path through desert and ancient ruins in his quest. But the human skull seen nearby warns of the hopelessness of trying to comprehend the unknowable. In ancient Greek mythology, the Sphinx is a monstrous hybrid of woman and lion. It has the potential to guide or destroy the wanderer, depending on whether one can answer the Sphinx’s riddle.

|

|

Fig. 2: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Fisherman and Genie, about 1863. Oil on panel, 7⅝ x 13⅞ inches. Bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer (06.2431). Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. © 2019, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. |

|

The collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age, and given its first English language edition in the eighteenth century under the title The Arabian Nights, inspired many of Vedder’s paintings of life-threatening encounters with monstrous creatures. Here, the narrative recounts how a fisherman outsmarts an evil genie after he caught a sealed-copper vessel in his nets and unintentionally released its deadly contents. Vedder depicts the moment when the terrified fisherman sees the fiend forming in the black billows that gush from the mouth of the vessel. Vedder’s preparatory sketch for the painting (Fig. 2a) suggests the impact of the war on his art. The drawing bears a striking resemblance to an 1861 caricature by Henry Louis Stephens—a friend of Vedder’s—published in Vanity Fair magazine (Fig. 2b), titled The Rising of the Afrite, in which a snake-wielding afrite (a genie), erupts from a bottle labeled “Secession.” An accompanying article interprets The Arabian Nights tale of “The Fisherman and the Genie” as an allegory of the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy. The similarities suggest that Vedder was condensing anxieties about the fate of the nation into one foreboding image.

|  | |

Left: Fig. 2a: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Fisherman and Genie, (n. d.). Graphite and gouache on beige paper. Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. Right: Fig. 2b: Henry Louis Stephens (1824–1882), Rising of the Afrite, in Vanity Fair magazine, January 1861. | ||

|

Beautiful and fair as the Nixes seem to be, the ruling principle retains its unity — the evil is only veiled — and the water-nymphs assert their affinity to the deluder, the tormentor, the destroyer. Inevitable death awaits the wretch who is seduced by their charms.

— Popular Mythology of the Middle Ages, Free-thinkers’ Information for the People

|

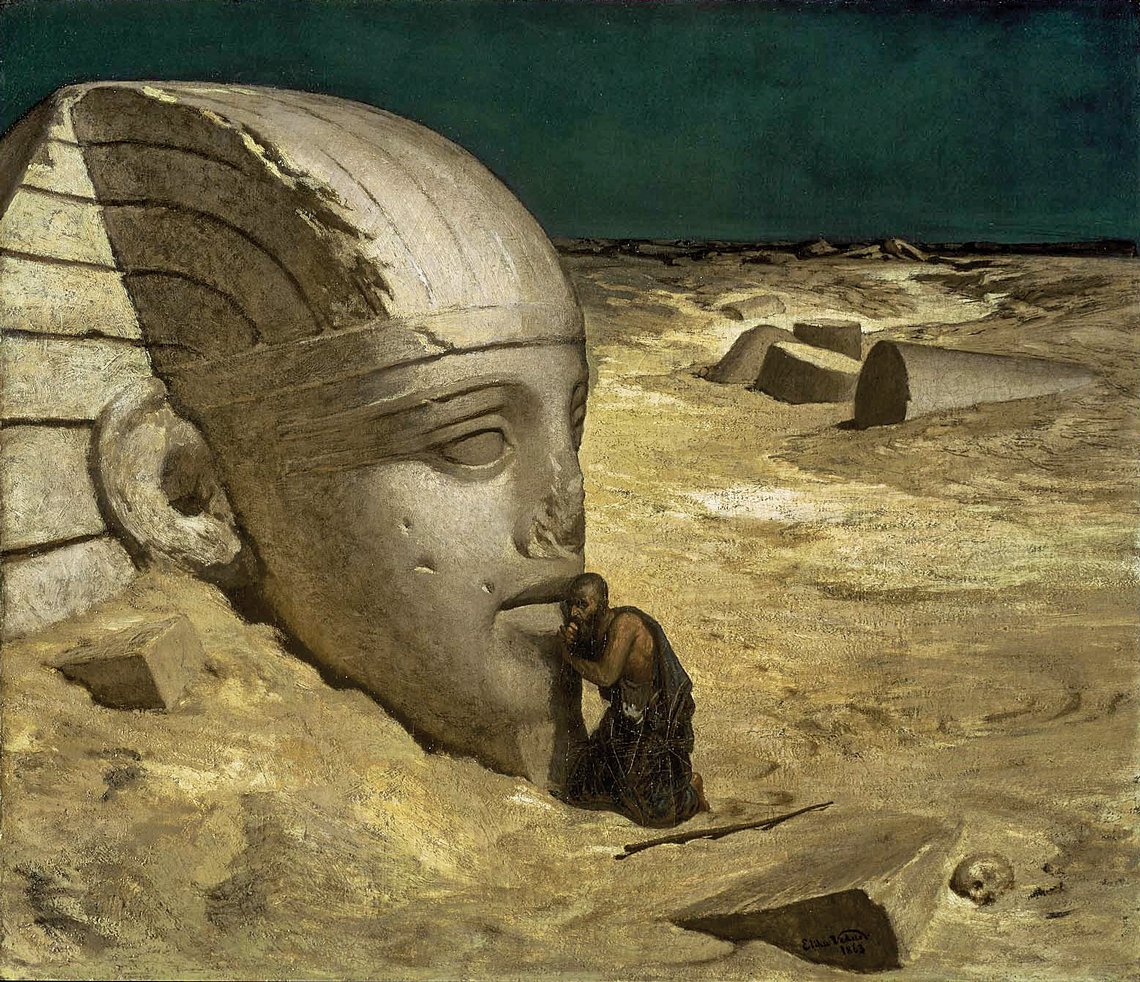

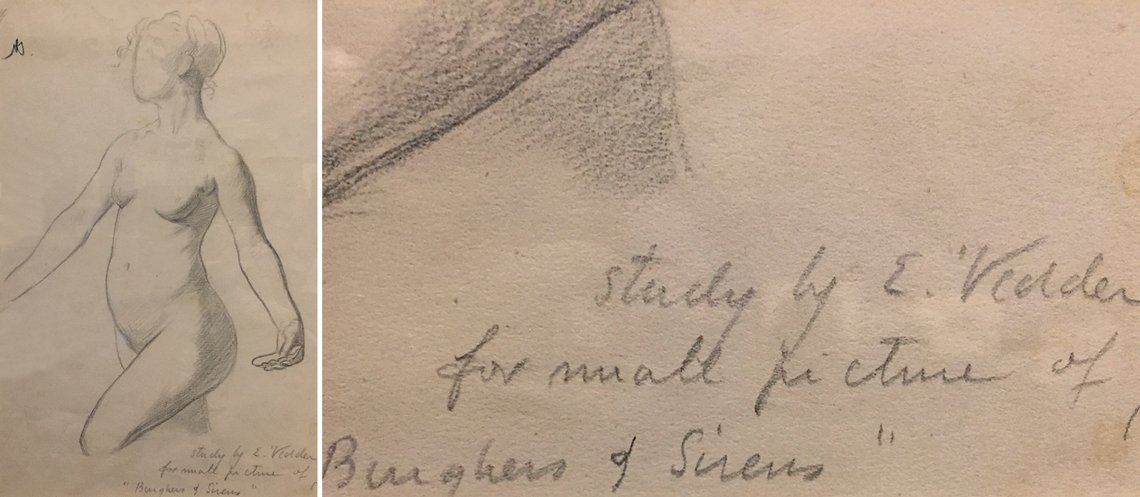

Fig. 3: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Burghers and Nymphs, 1872. Oil on canvas, 5½ x 12⅝ inches. Gift of the American Academy of Arts & Letters, 55.29. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute Museum of Art, Utica, N.Y. |

The discovery of eleven figure studies in the couple’s collection for the Munson-Williams painting, Burghers and Nymphs, led to a new interpretation of our picture. The female figures originally were considered playful water nymphs metaphorically making beautiful music with gallant gentlemen. However, the inscription in one of Vedder’s studies refers to the finished painting as “Burghers and Sirens” (Fig. 3b). Mythic stories abound of sirens luring men to their demise, suggesting once again the artist’s obsession with danger, evil, and death lurking beneath the surface.

One of the thrilling aspects of this exhibition was the re-discovery and inclusion of select works by Vedder from the former Harold O. Love Collection. I discovered the treasure trove thanks to a twenty-year-old phone number provided by Sarah Burns, Emeritus Professor of American Art, Indiana University. Apparently, after Harold O. Love’s death, his fascinating collection passed to his son and daughter-in-law, Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach.

The couple’s gracious loans, often of art never before seen in public, enabled exhibition visitors to further explore questions evoked by The Questioner of the Sphinx. The abundance of art inspired by legend and myth in the heirs’ collection contributed to academic scholarship as well as local programming. We included works from the exhibition in a school tour designed to support the Utica City School District curriculum. So over 6,500 sixth graders visited the museum and studied Vedder’s art as part of their class.

|

Fig. 3a: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Burghers & Nymphs, (n. d.). Pencil, 14 x 11 inches., Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. |

|

| |

| Fig. 4: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Phorcydes, (n. d.). Oil on canvas, 9 x 7½ inches., Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. |

This painting demonstrates Vedder’s on-going obsession with the theme of the wanderer encountering dangerous, nightmarish creatures. In Greek mythology, the Phorcydes were the three terrifying daughters of Phorcys and Ceto who presented the first obstacle that Perseus faced in his quest to slay the deadly Medusa. In order to proceed in his mission, Perseus needed to steal the one eye and one tooth the three sisters shared between them. Vedder depicts the tale at the moment the hero confronts the dreadful siblings. Their sinuous locks recall the snakes on Medusa’s head. They also anticipate a later motif Vedder developed to symbolize the soul’s journey from birth to death to rebirth.

|

|

Fig. 5: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Adam and Eve Mourning Abel, (n. d.). Oil on canvas, 4 x 13½ inches. Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. |

Adam and Eve’s son Cain represents the first wanderer in the Judeo-Christian tradition. The book of Genesis recounts the violent death of Abel at the hand of his jealous older brother Cain. For his crime, Cain was condemned to a life of wandering. Rather than depicting the murder scene described in the biblical story, Vedder chose to render the aftermath of Cain’s act, using color, light, and form to create a disturbing landscape that underscores the raw emotions of parents who have lost two sons. At the time Vedder painted this work, the story of Cain and Abel was often used as a metaphor for the national fratricide of the American Civil War.

|

| |

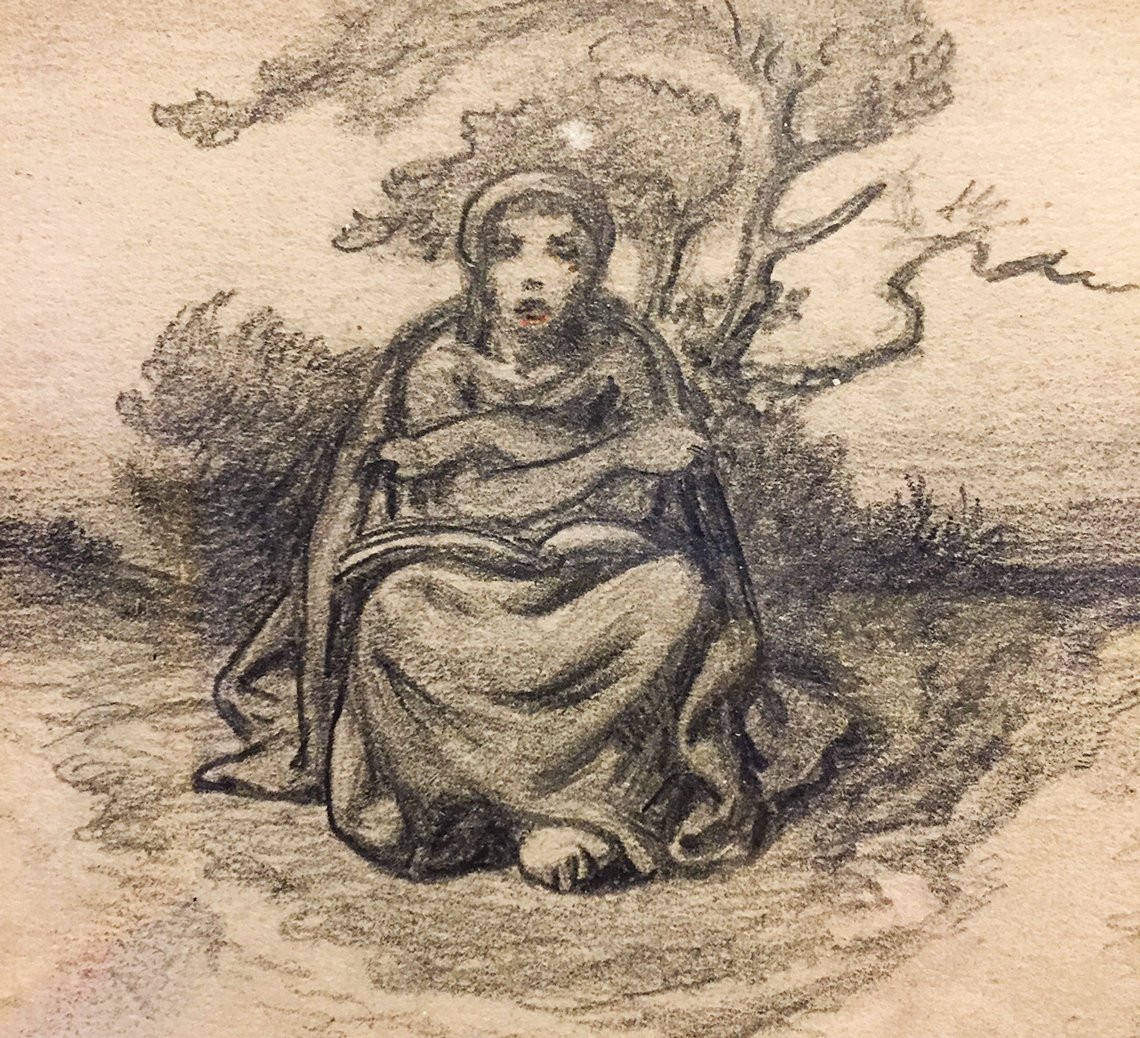

Fig. 6: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Woman Sitting at a Crossroads, (n. d.). Pencil on paper, 3⅞ x 7⅞ inches. Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. |

In The Questioner of the Sphinx, the desert wanderer symbolizes a search for direction and a longing for answers about the mysteries of life. Here, Vedder situates the viewer as the wanderer seeking answers from a figure who was associated with death and doom. Ancient Greek mythology called this figure Hecate (or Hekate), the goddess of the crossroads. She ruled the nighttime realm of ghosts, witches, and beasts, and had the power to either protect or set evil spirits upon the traveler. In Civil War America, journalists, writers, and cultural commentators often used the term “crossroads” to refer to the state of the nation. And, in fact, a number of battles were fought at a physical crossroads. The idea of a crossroads thus speaks to the complicated, intertwining, and multiple meanings of Vedder’s simple sketch.

|

| |

Fig. 7: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Fortune, (n. d.). Pastel, 20½ x 17-7⁄16 inches. Robert Love and Ardith Bausenbach Collection. |

The unpredictability of life was a recurrent theme in Vedder’s art. The Roman goddess Fortuna (Fortune), associated with both good and bad fortune, chance, and luck, embodied the fickleness of fate. The ancients considered Fortuna the force behind such events as floods, tornadoes, and war. Here, Vedder portrays Fortuna greeting the viewer with seemingly open arms. And yet the gloomy storm cloud she sits upon suggests fate’s darker side. An even closer look reveals that the deity has just cast some dice, suggesting the arbitrary nature of such states as prosperity and disaster.

|

| |

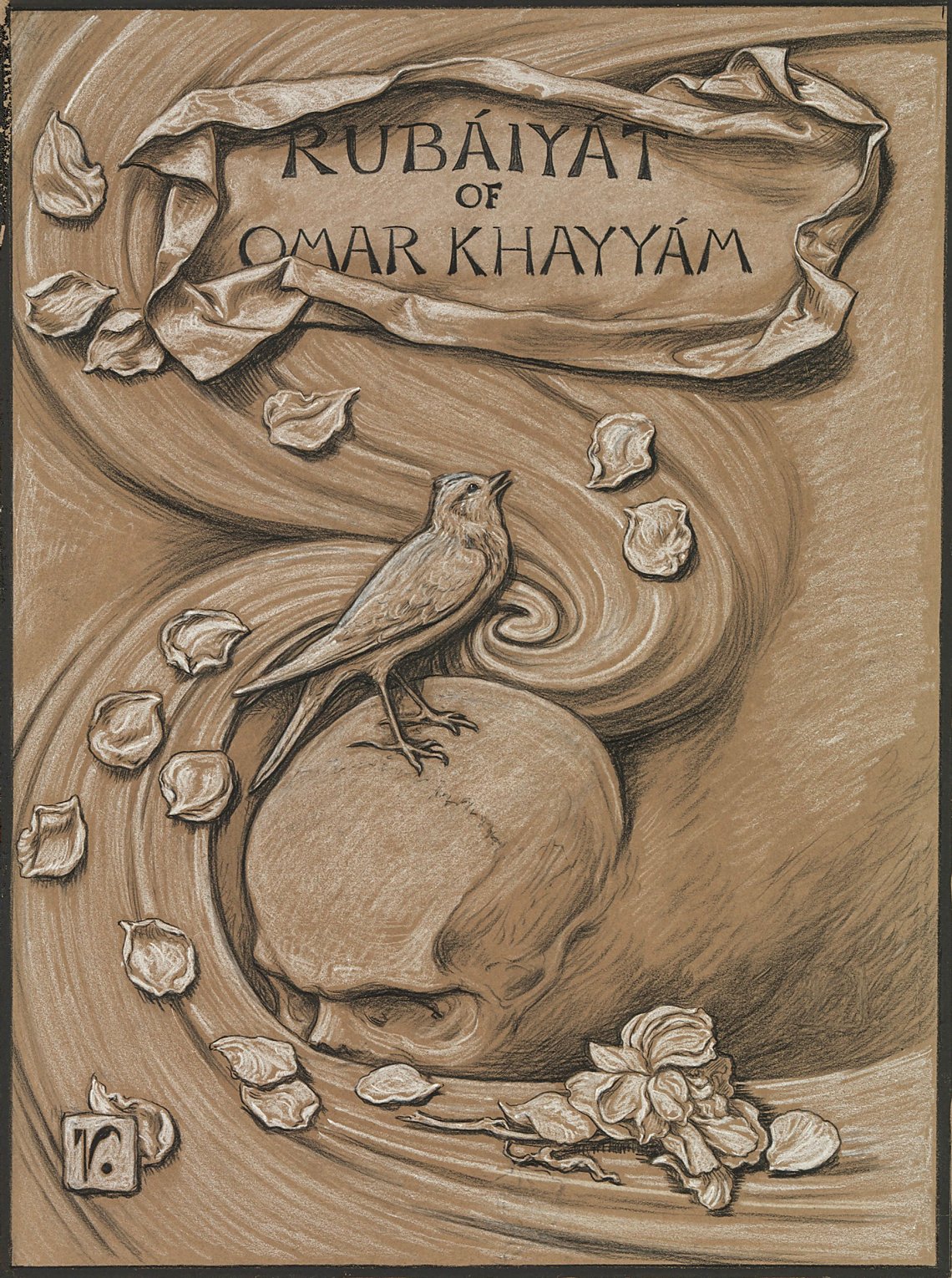

Fig. 8: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, The Astronomer-Poet of Persia, 1886, Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Rare Book Collection. |

The Rubáiyát is a collection of poems written by the Persian poet Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) to prove the futility of mathematics, science, and religion in determining the meaning of life. Vedder re-arranged the poet’s verses to express the three stages of existence, creating fifty-four drawings that enhanced the book’s melancholic mood. He developed an evocative visual language for the book’s imagery and design that combined traditional Christian symbols and ancient Greek and Roman figures with mystical forms of his own invention.

Vedder designed an emblem to represent his concept of the “cosmic swirl of life.” This “S” shaped, abstract representation of life, death, and the afterlife is a leitmotif that appears on the book’s cover and in many of its illustrations. According to Vedder, this cosmic design symbolized “The gradual concentration of elements that combined to form life; the sudden pause through the reverse of the movement which marks the instant of life; and then the gradual, ever-widening dispersion again of those elements into space.” The combination of Vedder’s images with Khayyám’s poems offered American readers a means for contemplating the mysteries of life and death that was especially attuned to the spiritual unrest of post-Civil War America. This may be why Rubáiyát became one of the most popular books ever published in the States, selling out in just five days and continuously reprinted until 1910. The publication probably introduced Art Nouveau to America, certainly revolutionized the art book industry, and brought Vedder fortune and fame.

|

| |

Fig. 9: Elihu Vedder (1836–1923), “Omar’s Emblem.” Frontispiece in Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, The Astronomer-Poet of Persia, ca. 1894, Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company, Special Collections, Burke Library, Hamilton College. |

Vedder visualized Omar’s melancholic ruminations on mortality in this singing nightingale, symbolizing life, standing poised upon a skull, symbolizing death. The transience of life is indicated by the fallen rose petals that float on Vedder’s leitmotif of the cosmic swirl of life. Vedder’s illustration appears to synthesize the existential themes he introduced twenty-three years earlier in The Questioner of the Sphinx. The wanderer’s circuitous path through the desert in the painting prefigures Vedder’s swirling visual theme. The artist also chose to depict a human skull half buried in the sand in the lower right corner of both painting and illustration. These visual parallels suggest that the enigma of existence haunted Vedder’s art long after the American Civil War ended.

|

Miranda Hofelt is the curator of nineteenth-century American art at Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York. For information, visit mwpai.org or call 315.797.0000.

|

1. The exhibition was on view from April 5–December 29, 2019.

|

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|