The Peabody Essex Museum

An Ever-Evolving Enterprise

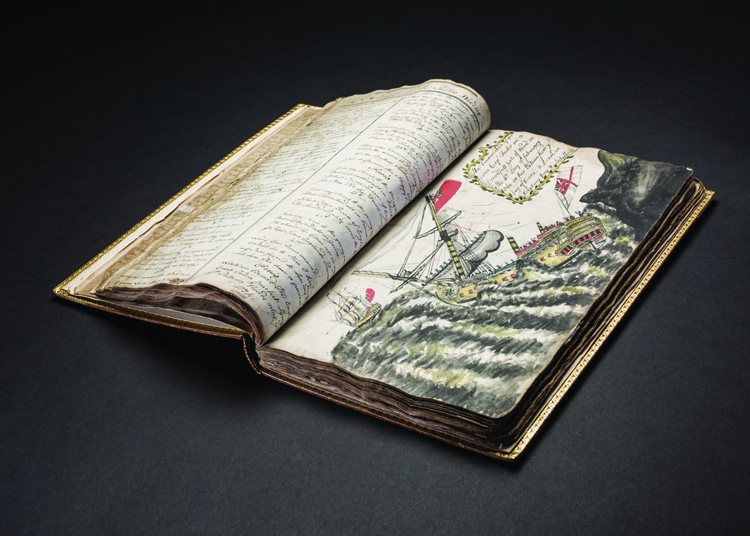

In 1799, several of America’s first entrepreneurs founded the East India Marine Society in Salem, Massachusetts. One of the Society’s primary goals was to establish a museum dedicated to collecting and presenting “wondrous works” from beyond the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. Few Americans had experienced the extraordinary diversity of people, art, and culture in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Most of the museum’s founders and supporters, however, had sailed to these places, often as the first Americans to undertake risky but highly profitable trading relationships. More familiar with Guangzhou (Canton) and Calcutta than with Philadelphia and New York, these seafaring businessmen developed international perspectives that were rare for their era and place. Determined that America would become one of the world’s great nations, they founded a museum to increase knowledge and appreciation of art and cultures dramatically different from their own. To create a museum of any kind in the United States—then only sixteen years old—was visionary. That a group of enlightened, philanthropic citizens would come together to make a museum accessible to all at no cost was an unprecedented act of public service.

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM)—the country’s oldest continuously operating museum—has evolved through a series of momentous changes. By the late 1860s, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia had superseded Salem as the locus of international trade, the Society’s founders were deceased, and the museum could not support itself. Selling the collection and the Society’s East India Marine Hall—constructed in 1825 and now a National Historic Landmark—loomed as an inevitable outcome. Similarly, the Essex Institute—founded in Salem in 1821 to collect American decorative art and later to pioneer historic preservation—faced bankruptcy. George Peabody (1795–1869), a native son of neighboring Peabody, an international businessman, and the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy, offered to save and underwrite the two museums under the condition that they merge. When the Essex Institute rejected Peabody’s extraordinary generosity, its president indignantly resigned. With the philanthropist’s funding, he purchased the East India Marine Society’s building and collection and reimagined it all as the Peabody Academy of Science.

- Figurehead, 2010. Charles Sandison (Born 1969, Scotland; works in Finland). Computer-generated data projection. Museum purchase, 2011. Purchased with funds donated by Mr. Alfred Chandler III and the Reverend Susan Esco Chandler, Nancy B. Tieken, Dan Elias, and Karen Keane, and the Anne Pingree Acquisition Funds. Photograph by Walter Silver.

The new institution flourished as a center of progressive study in the evolving fields of archaeology, anthropology, and natural history until the late 1870s, when financial difficulties became a recurring issue. In what proved to be a providential decision, the museum hired Edward Sylvester Morse (1838–1925) as its director in 1877. Morse was a brilliant, enterprising, and self-educated scientist and archaeologist. He is credited with founding the field of Japanese archaeology and became an internationally recognized expert on Japanese art and culture—ceramics and architecture, in particular. Under his leadership, the renamed Peabody Museum of Salem reinvigorated the East India Marine Society’s founding mission by focusing on Asia, Africa, Native America, and Oceania and acquiring tens of thousands of Asian objects. Subsequent directors continued to build the Oceanic, Native American, Asian export, and maritime collections up to the present day. In the 1970s, the museum expanded, and a decade later, it merged with the China Trade Museum and built a new wing devoted to a stellar Asian export art collection.

Just as George Peabody had proposed 130 years earlier, the Essex Institute and the Peabody Museum of Salem consolidated in 1992 to create the Peabody Essex Museum as an entirely new enterprise. The museum’s leadership developed a bold vision and mission dedicated to integrating art and culture in fresh ways that nonetheless resonate with the founders’ ideal of integrating the local and the global. In 2003, PEM not only opened a 113,000-square-foot wing designed by Moshe Safdie and renovated 170,000 square feet of existing facilities, but also completed a $194 million campaign. With these resources in hand, the museum repositioned and transformed its programs, staff, and facilities; launched a changing exhibition program and education initiatives; and unveiled innovative installations that showcase the collection’s depth, breadth, and interrelationships for the first time.

Now, just a decade later, PEM is the country’s fastest-growing museum, and our exhibitions, collection, interpretation, and programming express our founders’ adventuresome, cross-cultural values even more emphatically. Through 2019, the museum is engaged in a $650-million advancement campaign to underwrite creativity and innovation and to assure ongoing financial stability. The campaign is one of the largest in American museum history and the largest for a New England cultural institution. It is also the first art museum campaign dedicated to raising substantially more money for endowment than for facility construction. By 2019, PEM will rank among North America’s top ten museums in endowment and among the top fifteen museums in square footage and operating budget. Throughout the entire museum, including in a major wing to be designed by Ennead Architects, we will provide interpretative experiences and collection-inspired installations that incorporate many disciplines, including neuroscience. A greatly enhanced changing exhibition program and new public, education, and digital initiatives will serve audiences worldwide. In developing engaging on-site and virtual environments, we are questioning traditional concepts of a museum as an attraction or as a place principally oriented toward maintaining and contemplating art. We are reimagining the museum as a vital center for inspiring and experiencing the humanity, community, and potential that art and culture embody. Old and new, local and global, entrepreneurial and creative—these qualities define the past, present, and future of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Dan L. Monroe is the Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Director and CEO of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.