The Royal Academy of Sciences’ Bust of Benjamin Franklin

|

|

In 1949, France sent forty-nine World War I-era wooden railroad cars filled with gifts across the Atlantic to thank Americans for their aid in the aftermath of World War II. “Le Train de la Reconnaissance,” or the “Merci Train,” was a grass-roots effort to reciprocate for the “American Friendship Train”—a convoy of 700 railroad cars, packed with food and fuel sent by the American people to France and Italy in 1947.1

Among the treasures on the Merci Train was the bust of Benjamin Franklin that Franklin had presented to France’s Royal Academy of Sciences in 1785. Upon arriving in America, it was lost and forgotten—and with it, its remarkable history. This is the story of the bust of Benjamin Franklin and its probable recovery.

THE MERCI TRAIN

After the war, the French had very little, but an outpouring of donations from people wanting to contribute eventually filled forty-nine boxcars. Contents ranged from children’s drawings to museum-worthy relics such as Louis XV’s carriage. Included were such diverse offerings as cigarette papers, bottles of wine, vials of holy water from Lourdes, the bugle that signaled the end of World War I, and forty-nine mannequins dressed by top fashion designers to depict the history of Parisian fashion.2 The Academy of Sciences contributed their plaster bust of Franklin. (The “Royal” designation was removed from the title after the French Revolution.) Each item was distinguished with a label indicating its donor and regional origin.

Transported on the merchant ship the Magellan, the Merci Train arrived in New York harbor on February 2, 1949, to great fanfare, as widely reported in American newspapers. The boxcars were dispersed across the country: one boxcar designated for each state and one for Hawaii and Washington, D.C., to share (Fig. 1). According to Guy de la Vasselais, vice-president of the Gratitude Train Committee, the cargo was meant—not as gifts for individuals—but as “the permanent property of the people” for use in schools, museums and other institutions. Most of the contents, however, eventually disappeared; they were auctioned off, given to prominent individuals, sold, stolen, or consigned to storage somewhere without provenance (Fig. 2). The Franklin bust was one of these orphaned objects.

FRANKLIN IN FRANCE

The American Revolution was not going well when Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) arrived in Paris in December of 1776, sent by the Continental Congress to seek French aid. After losing the French and Indian War (1754–1763), France was not ready to risk another war with Britain—and was not at all convinced America could win. But even though the French government refused to openly acknowledge or assist the new country, they had begun sending covert aid. America, while grateful, desperately needed more.

Franklin was the best candidate for negotiations; his renown as a scientist and a man of letters had preceded him, and his membership in the prestigious Royal Academy of Sciences granted him access to people in important scientific, political, and social circles in France, crucial for achieving his diplomatic aims.

Commoners and aristocracy alike admired Frankin and everyone wanted a memento of him. As he wrote to his daughter Sally, “the pictures, busts and prints, (of which copies upon copies are spread every where) have made your father’s face as well known as that of the moon.” 3 King Louis XVI is said to have been so annoyed by this adulation that he commissioned a Sèvres chamber pot with Franklin’s face at the bottom, emblazoned with the Latin epigram that was to increasingly become associated with Franklin: “Eripuit coelo fulmen, sceptrumque tyrannis” (“He ripped lightning from the sky, and the scepter from tyrants”).

Franklin understood the propaganda value of his fame, so he seized the chance to sit for a bust by the celebrated artist Jean-Jacques Caffieri (1725–1792), sculptor to the king of France (Fig. 3) and professor at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Franklin also commissioned Caffieri to design a monument for America’s first fallen war hero, General Richard Montgomery (1738–1775), who had died fighting the British in 1775. Congress wanted the monument to be “procured from Paris, or any other part of France,” to demonstrate their economic and political solidarity with the French.4

Caffieri exhibited his plan for the memorial, with the original terra cotta bust of Franklin (Fig. 4), at the Salon of 1777. Caffieri is not known to have created a marble version of the Franklin bust, but he made a mold from the terra cotta original, which allowed him to cast multiple plaster busts for sale. Franklin was his best customer. Between 1778 and 1785, Franklin ordered at least eight plaster Caffieri busts for family and friends.5 As a consequence, Caffieri believed he had the prerogative to receive any future commissions from America.

In December 1777, after America’s spectacular victory at Saratoga, France recognized the United States of America as a sovereign nation and signed treaties in February 1778 as an ally. England immediately countered by declaring war on France. France could now openly join the American cause: contributing arms, supplies, and military support. King Louis XVI formally received Franklin at Versailles in March, validating his diplomatic status. Reflecting this new political situation, the 1779 Salon featured three portraits of Franklin—one of them a bust (Fig. 5) by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828).

Visitors flocked to the studio of the up-and-coming Houdon, especially to see (and purchase) his sculptures of the three emblems of the Enlightenment—Franklin, Rousseau, and Voltaire. Houdon’s star was on the rise, while that of Caffieri, once Houdon’s mentor and friend, began to wane (Fig. 6). A bitter rivalry developed. Not only had Houdon been commissioned to create a bust of Molière by the Comédie-Française, Caffieri’s own patron, but Houdon had sculpted a bust of Benjamin Franklin, implying on both counts Caffeieri’s had not been good enough.

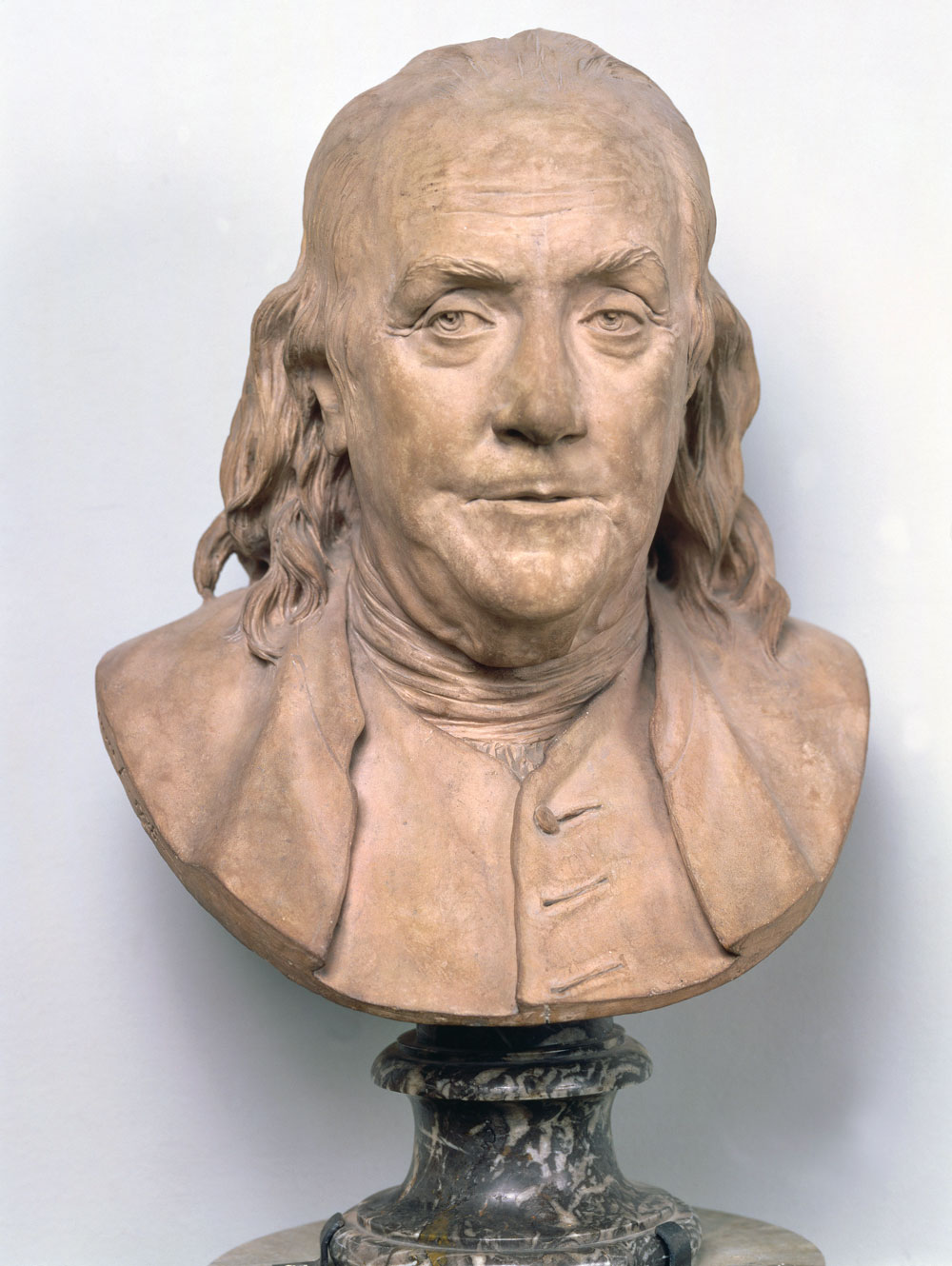

Houdon’s and Caffieri’s iconic works, created from life, together form our image of Franklin, but can be differentiated: Houdon’s version wears a coat with buttons while Caffieri’s version sports a loosely tied scarf (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Franklin never bought any of Houdon’s works and is thought to have preferred Caffieri’s rendition.

In the following years, Caffieri incessantly reminded Franklin of his desire—and expectation—to be appointed the official sculptor for America, and came to believe Franklin had promised him such a position. In 1781, with the British surrender and peace negotiations begun in Paris, he intensified his appeals to Franklin. And after the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, Caffieri learned that the United States of America wanted to commission a statue of General Washington. He petitioned Franklin to remember him.

In 1785, when Franklin was finally ready to return home, Houdon was to accompany him, having received the commission from the state of Virginia for the Washington statue. Bitterly disappointed, Caffieri exchanged a series of increasingly acrimonious letters with William Temple Franklin, who was serving as his grandfather’s secretary. Finally, close to Franklin’s departure, realizing it was fruitless to pursue his hopes any longer, Caffieri wrote to Franklin: “If my services in America could have been to your liking, I should have been most eager to accompany you, but you take with you one of my fellow artists, which is reason for me to hold my peace.” 6

In reply, Franklin reminded Caffieri that it was the right of each of the thirteen states “to employ what Artist it thinks proper, and is under no kind of Obligation to employ one who has been employ’d before…” 7 In the same letter, he ordered a plaster bust to be delivered to M. Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, of the Royal Academy of Sciences. Their association ended with this letter.

HOME TO PHILADELPHIA

Franklin and Houdon arrived in Philadelphia in September 1785. During his brief stay, Houdon modeled portraits of many of the heroes of the Revolution, including Washington, Jefferson, and John Paul Jones. Celebrated by prominent people and admired for his sculptures, Houdon’s name came to be associated with any bust of Franklin, while Caffieri’s name never became known in America. Back in Paris, Caffieri delivered the inscribed and signed plaster bust of Franklin to the Royal Academy of Sciences on February 13, 1788.8

Shortly after Franklin’s death in 1790, the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi arrived in Philadelphia, where, as a founding member of the first art academy in America, he helped bring the art of sculpture to America.9 Ceracchi’s marble rendition of Franklin was based on a plaster Caffieri version.10 Despite being a leading member of the art community, he did not have much luck selling his work, and so returned to Europe in 1794.

Because Houdon and Ceracchi were known in America while Caffieri was not, early collectors and museums attributed any Caffieri-type bust to either Ceracchi or Houdon. Caffieri’s correspondence with the Franklins, which would have linked him to the bust, lay undiscovered for many years in the archives of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

THE INSTITUT DE FRANCE

In 1795, during the upheaval of the French Revolution, the Royal Academy of Sciences merged with four other academies of arts and sciences to create an umbrella organization called the Institut de France. In 1805, it moved into the Palais de l’Institut de France, which already housed the Bibliothèque Mazarine, the oldest public library in France. Both Caffieri’s original terra cotta of Franklin (which had become part of the collection of the Institut de France in 1796) and the plaster bust from the Royal Academy of Sciences, were installed in the Palais de l’Institut: the terra cotta in the vestibule of the lecture hall of the Bibliothèque Mazarine, the Academy’s plaster bust in the grand hall of the Palais de l’Institut. The two busts were still in situ in 1879 when an inventory of French art recorded their locations and inscriptions.11

- Fig. 9: Jean-Jacques Caffieri (1725–1792)

Bust of Benjamin Franklin

Painted plaster, H. 28 Inches

Probably the cast originally delivered to the Royal Academy of Sciences, Paris, France in 1788 and from the original 1777 mold; then to Benjamin Franklin University in 1949; then to George Washington University, ca. 1987. The George Washington University Permanent Collection, courtesy of The Luther W. Brady Art Gallery. © 2015 The George Washington University.

CAFFIERI REDISCOVERED

In 1897, while researching Franklin portraits in the Stevens Collection in the Library of Congress, art historian Charles Henry Hart came upon Franklin’s 1785 letter addressing Caffieri’s complaints and ordering the bust. However, Caffieri’s name as recipient was not on the letter, which had been calendared as a letter to Franklin from “a discontented artist whose name is not preserved,” and that it was “possibly to Houdon.” Hart realized it could not have been meant for Houdon, since Houdon had traveled to America with Franklin, and therefore, had no cause for complaint. The artist also could not have been Ceracchi who had had no contact with Franklin.

Hart then discovered the extensive correspondence between Caffieri (an artist unknown to him) and the Franklins at the American Philosophical Society. He conjectured that Caffieri must be the “discontented artist,” and was perhaps the originator of the bust type that Ceracchi and others had later copied in marble. Even though there were references in the letters to Franklin’s orders from Caffieri for plaster busts, Hart did not know of any examples, and none of the marble busts were signed. So how was he to test his theory?

Franklin’s letter ordering a bust for the Royal Academy of Sciences inspired Hart to look for it at the Institut de France. A bust was indeed there and was of the type attributed to Ceracchi—and Caffieri had signed it. Hart’s theory was proven.12 In the following years, Hart’s attribution of this bust type to Caffieri was further validated when several plaster busts were discovered, including two inscribed and signed pieces: one now in the Royal Academy of Arts in London and one in the Royal Castle Museum in Warsaw, Poland (Figs. 7 and 8).13

On December 6, 1948, the Academy of Sciences donated their plaster sculpture to the Merci Train, believing it could be spared since they still had the terra-cotta bust in the Bibliothèque Mazarine.14 The bust traveled to Washington, D.C., where it was presented to Benjamin Franklin University in a ceremony on the steps of the U.S. Capitol in April 1949.

After that, little or no attention was paid to the location of the bust. When Benjamin Franklin University merged with George Washington University in 1987 the trail was lost. Any search for the bust has been complicated by the fact that, despite an accompanying letter from the Academy of Sciences attributing the bust to Caffieri, newspapers of the time reported that it was the original work by “the famous sculptor Houdon.” In 1962, historian Charles Coleman Sellers, in his seminal work, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture, documented known busts of Franklin by Caffieri.15 He located the terra cotta in the Bibliothèque Mazarine and the plaster bust in the Academy of Sciences. He did not know that the Academy of Sciences’ bust had been sent to America in 1949.

THE HUNT

In 2012, while researching Caffieri, I was unable to find an image of the bust. Hart had unknowingly pictured the terra cotta instead (as can be determined by a comparison of Hart’s photograph with photographs of the terra cotta bust) and it was not illustrated in Sellers’ book. According to the literature, the bust was still at the Academy of Sciences. When I wrote to the Academy of Sciences to request a photograph I was informed that there was no image and that it had been sent to America on board “Le Train de la Reconnaissance.” 16 I was unfamiliar with what this was and began to investigate.

In 2014, after a long search, I learned that a bust of Franklin by the “famous sculptor Houdon” had been given to Benjamin Franklin University.17 Fortunately, I found a photograph of the presentation ceremony, which showed a Caffieri bust, not an Houdon bust.18

In 2015, my search finally led to a bust that lay in a wooden crate in the off-site storage facility of the George Washington University Museum—with no associated files and covered with gold paint (Fig. 9). The trail of evidence, and the fact that it is inscribed and signed in Caffieri’s handwriting, leads to a deduction that this is the Academy of Sciences’ bust—and there is a way to confirm it. An 1879 inventory of French art recorded that the Academy of Sciences’ bust had a unique inscription: “Benjamin Franklin, ne a Boston le 17 janvier 1706, fait par J. J. Caffieri, en mars 1777; donne a l’Académie des Sciences, [date chipped off).19 If the phrase “donne a l’Académie des Sciences” is present, it would prove that the George Washington University bust is the one from the Academy of Sciences (Fig. 10).

Regrettably, thick paint now obscures the area where this phrase should be. Fortunately, there are two additional details that could move us closer to verifying that it is the bust. Recent photographs from George Washington University reveal that the words “en Mars” appear as noted in the 1879 inventory; this is not on any of the other three inscribed busts. In addition, it appears from the photographs that the word “Royale” is present. This could be part of the phrase “l’Academie Royale des Sciences,” the institution’s name before the French Revolution. In order to reveal the entire inscription, and thereby prove its authenticity, the bust requires conservation and scientific analysis. At that point, the gift from Benjamin Franklin, America’s first ambassador, would finally be brought to light.

CODA

On the basis of this article, the bust was taken out of storage and placed on view for the exhibition The Other 90%: Works from the GW Permanent Collection, at the Luther W. Brady Art Gallery, George Washington University in Washington, D.C., through June 3, 2016.

Pamela Ehrlich is an archaeologist, artist, and independent researcher.

The help of many generous people made this discovery possible. I wish especially to thank the late Mr. Earl Bennett, Madame Florence Greffe,

Dr. Artur Badach, Olivia Kohler-Maga and Lenore Miller of the Luther W. Brady Art Gallery, and my editors—Brian, Lara and Brenna Ehrlich.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with incollect.com.

2. The mannequins are now at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the bugle is at the Indiana War Memorial Museum.

3. Letter to Sarah Bache, Passy, June 3, 1779. Accessed from Franklinpapers.org.

4. Congress passed this resolution on January 25, 1775. The monument is now at St. Paul’s Chapel, Trinity Wall Street Parish, New York City.

5. All are unlocated (except perhaps the Academy bust). Other plaster busts exist but are not inscribed, signed, nor can be linked back to Franklin.

6. Charles Henry Hart and Edward Biddle, Memoirs of the Life and Works of Jean-Antoine Houdon: The Sculptor of Voltaire and of Washington (Philadelphia, 1911), 94.

7. June 20, 1785, Hart and Biddle, 77–78.

8. The delivery was noted in the minutes of the meeting of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Feb. 13, 1788, a copy of which was sent to me by Mme. Florence Greffe, Chief Archivist, Royal Academy of Sciences, Paris.

9. See Wayne Craven, “The Origins of Sculpture in America: Philadelphia, 1785–1830.” American Art Journal 9, no. 2 (Nov., 1977): 4–33 for information about Houdon and Ceracchi’s influence on the beginning of sculpture in America.

10. It is apparent that at least one plaster Caffieri bust had reached Philadelphia. In 1789, the Pennsylvania Hospital sent a bust to Italy to serve as a model for a statue of Franklin for the Library Company. The statue sports a Caffieri style head. The Pennsylvania Hospital bust is presumed lost.

11. Inventaire général des richesses d’art de la France, 1879, Vol. I–II (Pion: Paris) 13, 310.

12. His discovery is detailed in Charles Henry Hart and Edward Biddle, “Memoirs of the Life of Jean Antoine Houdon,” (1911).

13. The Royal Academy bust was donated in 1791 by Pahin la Blancherie, who had acquired it in 1783 from William Temple Franklin. The Warsaw bust is figure 7, 8.

14. This was recorded in the Dec. 6, 1948 meeting notes of the Academy of Sciences. Mme. Florence Greffe sent a copy to me.

15. Charles Coleman Sellers, Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962), 197–203.

16. Personal communication from Mme. Florence Greffe, March 23, 2012.

17. In a personal communication, March 27, 2012, Mr. Earl Bennett wrote: “I also recall that the bust was said to have gone to a Franklin Museum.” Unfortunately, he updated his website in April, after this email, posting the information that the bust had been given to Benjamin Franklin University. He did not inform me and I did find it until 2014. His post noted that the bust had been crafted by the 17th century sculpture [sic] Houdon.

18. Friday, April 8, 1949, Richmond Times Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 26. Accessed from genealogybank.com, copyright of Newbank.

19. Inventaire général des richesses d’art de la France, 1878, Vol. I–II (Pion: Paris) 13, 310.