The Second Rediscovery of Cosme Tura

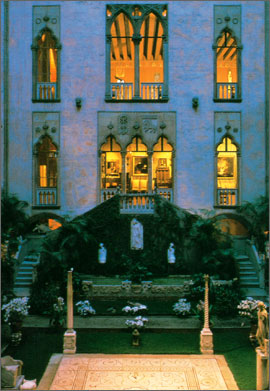

Although Cosmè Tura (ca. 1430–1495) was one of the great painters of the generation that included Botticelli, Mantegna, and Leonardo da Vinci, he is now far less well known than his contemporaries. A century ago, however, when the estimable collector Isabella Stewart Gardner acquired a work by Tura for her Fenway Court Museum in Boston, the artist was widely admired. Tura had been “rediscovered” a generation earlier by English collectors like Henry Layard and Sir Charles Eastlake and by scholars such as Adolfo Venturi and Bernard Berenson (who advised Gardner on the purchase in 1901).1 The National Gallery in London acquired Eastlake’s spectacular Turas in 1867 (Fig. 1) and in 1916, the resplendent panel formerly owned by Layard (Fig. 2). In the early decades of the twentieth century, North American collectors and art museums made significant Tura acquisitions. By 1917, works by Tura were owned by John G. Johnson of Philadelphia, Theodore Davis of Newport, Harold Pratt of New York, and The Fogg Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts; a manuscript with an illumination attributed to Tura was acquired by John Pierpont Morgan, Jr., in 1927. These works, along with paintings, drawings, and objects from European collections, will be on display at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Spring 2002 in the very first exhibition devoted to Tura and his place in fifteenth-century art.

Gardner acquired her Tura at a time when Berenson (the art historian, critic, and connoisseur) was solemnly proclaiming him the founder of one of the great schools of Italian painting: “Of the young men who flocked to Padua, none brought greater gifts, none drank deeper of Donatello’s art, and none had a more remarkable destiny than Cosimo Tura….It was destined that from him should descend both Raphael and Correggio.”2

Tura was eulogized again in the writings of the great Italian scholar Roberto Longhi, who published his influential Officina Ferrarese in 1934. The preceding year, a great exhibition in Ferrara that was devoted to the city’s Renaissance artists received international attention. Tura was the central figure in this exhibition, with twenty-two works displayed—about half of his surviving oeuvre.

Tura particularly appealed to a post-Victorian generation who had witnessed the horrors of the First World War and wanted something more from Renaissance art than the calm, “Pre-Raphaelite” elegance of Botticelli. The artist’s early-twentieth-century admirers had seen the emergence of cubism and expressionism; their eyes were attuned to an expressive distortion of the figure that Tura, alone among all early Renaissance artists, seemed to convey. Venturi found Tura’s works to be “marked with the violence of the rougher passion.” Berenson described his figures “as convulsed with suppressed energy as the gnarled knots in the olive tree.”

The Gardner exhibition is the first significant showcase of Tura’s work since 1933. This raises the question of why—especially given the enthusiasm of turn-of-the-century collectors—Tura was so neglected by museums and the public for much of the remainder of the twentieth century. One reason is that the city of Ferrara, which had once occupied a place in the Victorian and Edwardian imagination, no longer attracted droves of foreign visitors. The American tourist in Italy in those earlier romantic times knew of Ferrara as the birthplace of celebrated Renaissance poets such as Ariosto and Tasso, as well as the setting of Robert Browning’s famous poem “My Last Duchess,” which commemorated a lurid episode in the private life of the city’s ruling family. Ariosto, Tasso, and Browning do not have the same resonance for our postiromantic generation, and fewer tourists from North America now make a detour to the medieval, walled municipality of Ferrara. One great work by Tura remains there—his organ shutters for the cathedral—plus two jewellike fragments of a destroyed altarpiece (one of which is shown in the Gardner exhibition). Yet in the late nineteenth century, despite colossal losses to its artistic heritage, Ferrara was the object of a melancholy attraction for the visitor to Italy, a kind of romantic ruin at the center of the Po Valley. As with Naples and Milan, scholars and tourists were drawn to the remnants of an artistic culture that had been largely lost.

The process of destruction and dispersal of Ferrarese art was well under way by the end of the sixteenth century. Many of the city’s churches and palaces had been damaged by wars, by a devastating earthquake in 1570, and finally, in 1598, by the city’s return to the overlordship of the Papacy. The ruling dynasty, the Este, had been expelled, and the city was given over to centuries of looting and neglect under the papal rulers. The more famous paintings once owned in Ferrara, by Venetian artists such as Titian and Bellini, found their way into various Roman collections, finally ending up in the Prado or, since the last century, in the London and Washington national galleries. But the fifteenth-century works by Ferrarese painters, deemed less prestigious and less collectible, were poorly preserved. When nineteenth-century local collectors became interested in the Ferrarese quattrocento, the original functions and locations of the fragmentary paintings had been largely forgotten.

The dissemination of Ferrarese patrimony is one obvious explanation why the works of Tura, and other Ferrarese artists, are not better known. Another reason is that from the 1930s until recently, Tura was categorized by art historians in a way that was detrimental to his recovery. He had spent a large part of his career working for the court of Ferrara; therefore, the idiosyncrasies of his style, which twentieth-century writers at times characterized as “berserk” and “grotesque,” were rationalized as “court taste.” “Court style” connotes a retardataire, late Gothic character, of escapism and luxury. On the other hand, Florentine art was described in terms of the intellectual values that flourished under a “free Republic.” Such dichotomies are products of Cold War-era thinking, and they hardly characterize artistic style. Many artists in the “free Republic” of Florence—Filippo Lippi, Masolino, Botticelli —are just as “courtly” (i.e., preoccupied with ornament, luxury, and refined expression) as Ferrarese artists, if not more so.

-

Fig. 2: An Allegorical Figure (A Muse (Calliope?), probably 1455–1460. Oil with egg in the first version (identified on wood), 45 7/10 x 28 inches. ©National Gallery, London. Tura’s Calliope, with her corporeally expressive twist, her opened dress, her plucked brows, and her eyes coolly averted from the observer, seems to revel in precisely the sensual appeals that made pagan culture and its literary legacy so disturbing to opponents of humanism. This conception defiantly affirms the Christian condemnation of the Muses as “Sirens and harlots of the theater,” dangerously seductive to men.

The category of court style does not explain Tura’s harrowing images of saints and religious mystics, such as The Martyrdom of Saint Maurelius (Fig. 3) and St. Jerome, whose expression registers the agony of self-flagellation and the rapture of a vision of the crucifix.3 This work, as with so many of Tura’s surviving images, was conceived for a public that may have included the court, but that was much larger than the court: It would have consisted of the religious order in whose church the work was placed and the lay public who would have encountered it there.4 Several of the fragmentary works assembled for the Gardner exhibition have been brought together for the first time since their dispersal centuries ago. These fragments largely represent portions of altarpieces made not for the Este dynasty, but for aristocratic patrons such as the Roverella family.

The great Roverella polyptych was made in the 1470s for the Church of San Giorgio, the original cathedral of Ferrara and the memorial to a family who rivaled the Estes in local and national importance. The altarpiece owes its present ruined state to a rather spectacular misadventure: a missile attack by papal forces on Austrian troops occupying San Giorgio in 1709. Four fragments of the altarpiece are displayed in the current Boston exhibition, including three round predella panels and Circumcision from the Gardner’s collection (Fig. 4); the larger portions, now in The National Gallery in London (Fig. 1), the Colonna Collection in Rome, and the Louvre, are too fragile to travel.

The altarpiece was one of Tura’s most important works: It is strikingly festive in effect, appearing to exult in its own arbitrary character and variety of both color and ornament. It is reminiscent of Tura’s role as a designer of decorative arts who specialized in ephemeral set pieces for ceremonial occasions.5 But the Roverella altarpiece was not designed solely to provide visual pleasure; there was an explicitly polemical end in view. A clue to that controversial intention is manifested in the panel of the Virgin and Child (Fig. 1), in which the head of the sleeping child obscures part of an inscription in Hebrew: none other than the second commandment, “Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of anything that is in the heaven above, or in the earth beneath…” (Exodus 20:4).

The Jewish proscription against the making of images had long provided Christianity with a basis for distinguishing itself from Judaism. The interdiction of the image in Mosaic Law was countered by the theology of Incarnation, which legitimized the use of images in Christian worship by maintaining that Christ had appeared in visible and material form on earth.6 The papacy of the Franciscan theologian Sixtus IV was particularly preoccupied with the need to ground the roots of Christianity in Judaism, yet felt a simultaneous need to draw lines of demarcation between Jew and Christian. The Roverella brothers commemorated in the altarpiece—Lorenzo, Bishop of Ferrara, and Bartolomeo, Cardinal of San Clemente—were agents of papal jurisdiction and monitors of ideology in their home territory of Ferrara. The anti-Semitism of the Roverella altarpiece can be seen as an implicit critique of one core feature of Este policy: the fact that the Este rulers had long protected the Jews in Ferrara and allowed them to run banking operations despite massive opposition from Franciscan and Dominican preachers. While at the time of its creation the ideological meaning would have been understood, Tura’s work has only recently been considered to speak so eloquently, if disturbingly, on matters of cultural conflict within the time and place of its production.

Another history, the rise of humanist culture in Italy, was one of the central manifestations of the Renaissance. A magnificent example of this thought is one of Tura’s greatest paintings: the image of a pagan goddess—most likely Calliope, leader of the nine Muses, who in Greek and Roman mythology presided over the arts and sciences, particularly poetry (Fig. 2). Despite its visual splendor, the work does not merely exemplify “courtly” values of ostentatious display; it refers to humanist theory.

The Muse has the rare distinction of being one of the earliest large-scale mythological images from the Renaissance, and one in which the scholarly values and literary enterprises of the humanist movement are clearly reflected. The Ferrarese court was a source of patronage for some of the leading Greek and Latin scholars of the age who introduced the myths and arts of ancient times. To a remarkable degree, these scholars concerned themselves with the visual arts: They wrote poems in the ancient manner that extolled the beauties of painting and tapestry and paid lavish tribute to celebrity artists such as Pisanello.7 A new way of valuing painting came into being at the court of Ferrara, a tendency to think of painting not merely as a mechanical art (the normal point of view of men of letters), but as something akin to literary discourse. The great humanist Guarino of Verona, who produced a set of written instructions for painting the Muses, insisted that painting and writing were the same thing and that painting possessed the nobility of writing. With the “Pratt Madonna” (Fig. 5), Tura gives a very literal interpretation of this view: The jagged outline and sharp drapery folds evoke the broken forms of Gothic calligraphy that appear on the Virgin’s decorated bench. Tura’s Muse can be seen as an icon for humanists, whose poetry shows that they thought of antiquity not in terms of sober moral probity and Stoical ethics, but as an endorsement of intellectual curiosity and sensual experience.

Along with new insight into the cultural context of Tura’s art, technical knowledge of his work has been greatly enriched in recent years.8 In the 1980s, conservators in Ferrara and at The National Gallery in London began a systematic conservation and technical examination of Tura’s work. Infrared reflectography revealed extraordinarily detailed yet vigorously executed drawings in black pigment, sometimes reinforced with white heightening. This was unusual in an Italian context; the only real fifteenth-century parallel to Tura’s underpainting technique was in the work of Leonardo da Vinci.9 The making of detailed drawings on panel was also a distinctly Netherlandish technique. Tura then emerged as one of the earliest Italian artists to use an oil-based technique as Netherlandish masters such as Rogier Van der Weyden had used it: to create rich and lustrous effects by laying down transparent layers of pigment over a white background. His paintings echo the appearance of Northern art, but also manifest something different—something distinctly Ferrarese, it might be said.

The richness of Tura’s art is to some extent a result of its assimilative quality, its intelligent command of Transalpine and Italian styles. Tura’s command of perspective, his sense of pictorial structure, and his stylization of forms respond to a court taste that was conditioned in part by the acquaintance of his patrons with Mantegna and Piero della Francesca, while the expressive and mystical quality, together with his manipulation of an oil-based technique, was a response to Northern art.

- Cathedral at Ferrara. Photo by Jim Steinhart of www.PlanetWare.com.

The currency of Tura’s “Ferrarese” language was short lived and probably obsolete by 1490, five years before his death, when he would write to the Duke of Ferrara, claiming poverty, illness, and an inability to work or collect his debts from renegade clients. A new artistic language had arisen in the centers of the Papal State: The pellucid color and serene contemplative quality of Perugino’s work now held sway. Such rapid transformations in the “modern manner” following the death of Tura began the long and dismaying process of his erasure and oblivion, a process that would continue until his partial rescue from obscurity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After several decades of interruption, the recuperation of a great Renaissance master is taking place once again.

-----

Stephen J. Campbell is Assistant Professor of History of Art at The University of Pennsylvania and the author of Cosmè Tura of Ferrara: Style, Politics and the Renaissance City 1450–1495 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998). He is guest curator for the exhibition Cosmè Tura: Painting and Design in Renaissance Ferrara, on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, from January 30 to May 12, 2002.

2. Berenson, Italian Painters of the Renaissance (New York: Phaidon Publishers, 1952), 159. Cosmè Tura is also referred to as Cosimo Tura.

3. A separate fragment of the original larger panel showing Jerome’s vision of the crucified Christ is now in Milan at the Brera Gallery.

4. See Stephen J. Campbell, Cosmè Tura of Ferrara: Style, Politics and the Renaissance City 1450–1495 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 80-90.

5. Tura was also responsible for producing the “house style” of the Este court. Primarily, however, this was in the capacity of designer, as a maker of patterns for other craftsmen (silversmiths, tapestry weavers, embroiderers, armorers, painters). This aspect of Tura’s output has been largely lost, but the Gardner exhibition includes several precious examples of Tura’s activity as a designer: bronze medals of an infant Este prince and of his parents and a tapestry altar-frontal as well as several illuminations and a portrait that constitute emulations of his style by other Ferrarese artists.

6. See Herbert Kessler, “Pictures Fertile with Truth: How Christians Managed to Make Images of God without Violating the Second Commandment,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 49/50 (1991/92), 53–65.

7. See Michael Baxandall, “A dialogue on art from the court of Leonello d’Este: Angelo Decembrio’s De Politia Litteraria Pars LXVII,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 26 (1963), 304–326; and idem “Guarino, Pisanello and Manuel Chrysoloras,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 28 (1965), 183–205.

8. Tura has been the subject of no less than three monographic studies since 1997. In addition to Campbell, Cosmè Tura of Ferrara, see Joseph Manca, Cosmè Tura (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 2000), and Monica Molteni, Cosmè Tura (Milan: F. Motta, 1999).

9. As pointed out by Jill Dunkerton, “Cosimo Tura as Painter and Draughtsman: The Cleaning and Examination of his Saint Jerome,” The National Gallery Technical Bulletin 15 (1994), 42–54. For the technical analysis of the Pietà by Tura at the Museo Correr in Venice, see Attilia Dorigato, Carpaccio, Bellini, Tura, Antonello e altri restauri quattrocenteschi della Pinacoteca del Museo Correr (Milan: Electa, 1993), 12, 58–61, 103, 145–152, 231–233.