The Splendor of Cuba

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465–1524) of Spain led the first expedition to colonize Cuba in 1511, founding Cuba’s first seven towns: Baracoa (1512), Bayamo (1513), Santiago de Cuba (1514), Sancti Spiritus (1514), Trinidad (1514), Santa Maria del Puerto del Principe (1515), and Havana (1515). With Havana’s natural harbor as a strategic springboard for trade, Cuba was the most important outpost of the Spanish empire by the last quarter of the sixteenth century.

Toward the end of the century, Cuba’s supply of gold was all but exhausted and the island’s oligarchy began to concentrate on agricultural potential. In addition to the exportation of tropical hardwoods, tobacco plantations began to prosper, bringing wealth to the island, particularly to Havana, which became the center of the production and dispatch of tobacco for the entire Spanish empire.

Spain’s demand for tobacco, initially touted as a medicament, was in time matched by the popularity of coffee, first brought to Cuba in 1748. By the mid-eighteenth century, another commodity was also well entrenched — sugar, or “white gold.” The first sugar plantation was established in Cuba in 1576. The island proved ideal for the proliferation of sugar cane and during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries this “economic miracle” brought untold riches to Cuba.

By the 1590s, professional builders and artisans had emigrated from Spain to the island of Cuba. The first impulse was to impose European designs and building traditions. In Spain this was the baroque, which featured fanciful façade decorations and elaborate curvilinear motifs and elements. Until the mid-seventeenth century, most of Spain’s craftsmen and artisans were of Moorish descent and still practiced Moorish-Hispanic craft techniques and aesthetics. As a result, the early Cuban colonial built landscape was permeated by Mudéjar, or Hispanic-Moorish, traits. This fusion of Muslim and Christian decorative devices was characterized by intricately carved woodwork in ceilings and balconies, patterned brick and stucco arches, and intricate interlaced geometric patterns in tile work, metalwork, and furniture, with modifications made for the island’s tropical climate and available building materials.

In the eighteenth century, domestic architecture saw a more gradual process of adaptation and assimilation, and two distinct architectural fashions were popular. Alongside the Mudéjar and baroque influenced styles, a more austere trend was also popular; one that was plain except for occasional decorative elements and architectural fittings on the facades, usually around covered porticoes.

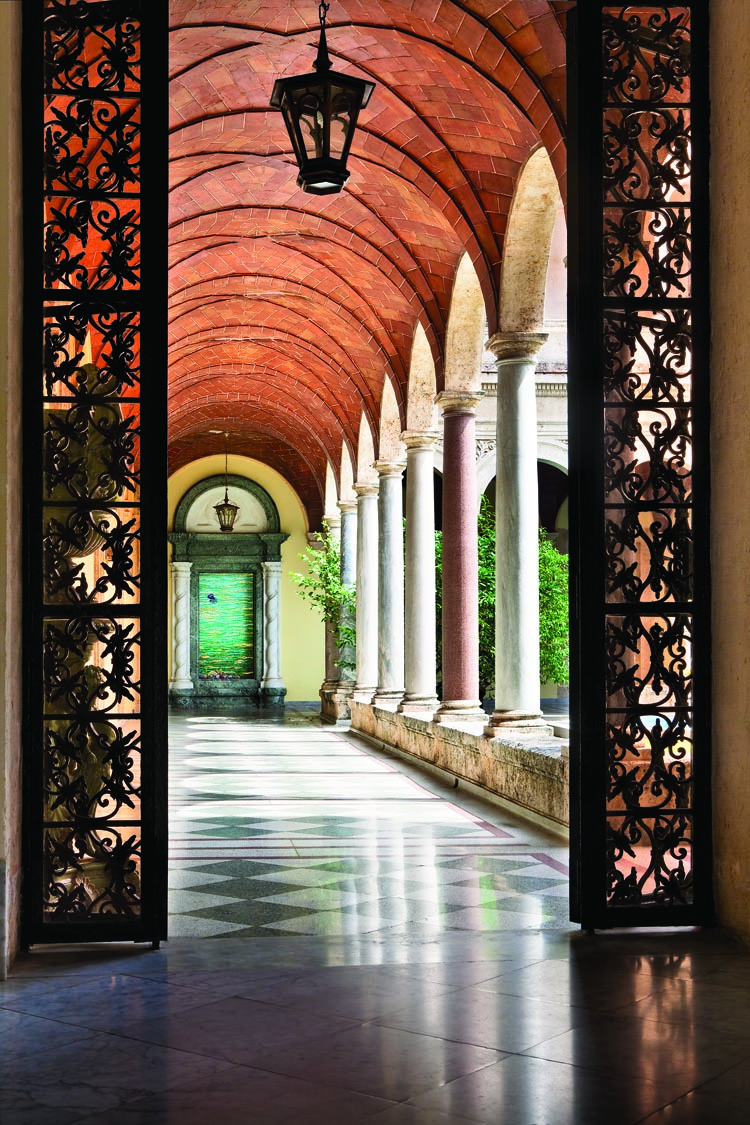

Spanish and European architectural trends and the need to further adapt to the tropical climate eventually brought about a specific style, that of the Cuban baroque. Urban houses featured enclosed inner courtyards surrounded by arcades, balconies that faced the street, and ornamental facades. The new style transformed the appearance of the island’s urban towns and cities. Baroque-style mansions contained the most fashionable furnishings and embellished interiors, many with elaborately carved Mudéjar ceilings, imported Italian marble floors, radiant glazed tile work, plasterwork, and spectacular fanlights.

During the last half of the eighteenth century, the Cuban baroque style reached its peak, and Cuban domestic architecture became even larger and grander. Cuba’s prosperous landowners continued to seek only the latest fineries from Europe, and, with trade restrictions lifted during British occupation in 1762-1763 at the end of the Seven Years’ War, the wealthy class imported luxury goods from France, England, and Holland, as well as from Spain.

Cuba entered a new phase of development in the nineteenth century, one that many historians consider the beginning of the island’s modern era in that central factories were established for the processing of sugar, railroads were built, free trade was further developed and foreign capital was invested in the island. This new century of expansion and prosperity proved unprecedented in Cuban history.

At this point, the Cuban baroque style began to bow out entirely and Cuba’s new “sugar palaces” were designed in the more fashionable neoclassical style, with tall classical columns and engaged pillars. In addition, there were large enclosed, but airy, courtyards and patios with surrounding galleried arcades incorporating columns, balconies with intricately carved classical arches, and shuttered windows and doorways.

The nineteenth century saw a division in Cuba between those of more recent Spanish origin and the Cuban-born Creole inhabitants. The former, many of whom held new pseudo titles created and awarded by the monarchy as incentive to immigrate to the island, were assigned influential governmental jobs. The Creoles, who owned the biggest plantations, were largely responsible for the development and success of the island’s economy. In time, a passionate loathing grew between these two privileged classes of islanders, with Cuba’s wealthy Creole class feeling alienated from Spain. This ultimately drove the colony toward a desire for independence from the mother country. The combination of the emancipation of slaves in 1886 — the major labor force, mainly from Africa, responsible for upper-class wealth — and the War of Independence from 1895–1898, brought about the decline of the sugar economy and saw the beginning of the dissolution of Cuba’s plantocracy.

Cuba’s new independence spawned a push for modernity in domestic architecture at the turn of the twentieth century. After the Spanish-American War in 1898, resulting in Cuba’s independence from Spain, the United States occupied the island until 1902. For the next three decades, billions of dollars from U.S. investments resulted in the growth of a new middle class and an expanding upper class, and were responsible for a building boom that created new suburbs throughout Cuba as well as massive civic constructions and public utilities. Architectural styles like the art nouveau, Beaux-Arts, and art deco blossomed in cities all over the island. By World War I, the influx of new wealth brought about a new era of building plush, grand mansions in the eclectic, neoclassical, and Beaux-Arts styles.

In the 1940s, modernism came into its glory in Cuba. It peaked in the 1950s, when thousands of new homes were designed in the contemporary fashion in the suburbs of towns and cities throughout the island. By the 1960s, Cuba’s architectural revolution abruptly ended. Following the Communist Revolution (1953–1959), most of the leading architects left the island and, in 1965, the School of Architecture closed, signifying the end of Cuba’s significant architectural development.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com

To read more on Cuba’s architectural history, see Michael Connors’ The Splendor of Cuba: 450 Years of Architecture and Interiors (Rizzoli, October 2011).

This lavishly illustrated 320-page volume contains 295 color photographs (ISBN 978-0-8478-3567-6).

For information visit www.rizzoliusa.com.