The World of Charles and Ray Eames

| |

Ray Eames, Study for Crosspatch textile design, 1945. © Eames Office LLC. |

T he world of Charles and Ray Eames was multifarious and constantly expanding. Now widely considered two of the foremost designers of the twentieth century, this couple — in life as well as in work — worked collaboratively with the members of their studio, the Eames Office, on a myriad of projects, ranging from iconic furniture to playful toys to pioneering multimedia installations. Their celebrated products and approach to design have become emblematic of a Californian attitude.

Charles Ormond Eames Jr. (1907–1978) and Bernice Alexandra “Ray” Kaiser Eames (1912–1988) were true polymaths. The couple’s interdisciplinary practice came to define their work and prefigures how many contemporary practitioners work today. Pulling from a diverse range of source materials, together with their team of staff they amassed an extraordinary output. They had an intensive research process, always testing their ideas by creating scale models as well as exploring inventive approaches to understanding subject matter, often through film and photography. To take just two examples, they experimented tirelessly with new fibreglass production processes to create the most comfortable and affordable single-piece chair, and they made a poetic film studying the life of marine sea creatures to help them learn how to build the best environment for an aquarium. They were fascinated by different modes of visual communication, leading them to embrace burgeoning computer technologies in both their work and teaching. Design for them was a way of life, a process of problem solving that was continually evolving.

|

|

Molded-plywood aeroplane stabilizer, ca. 1943. © Eames Office LLC. |

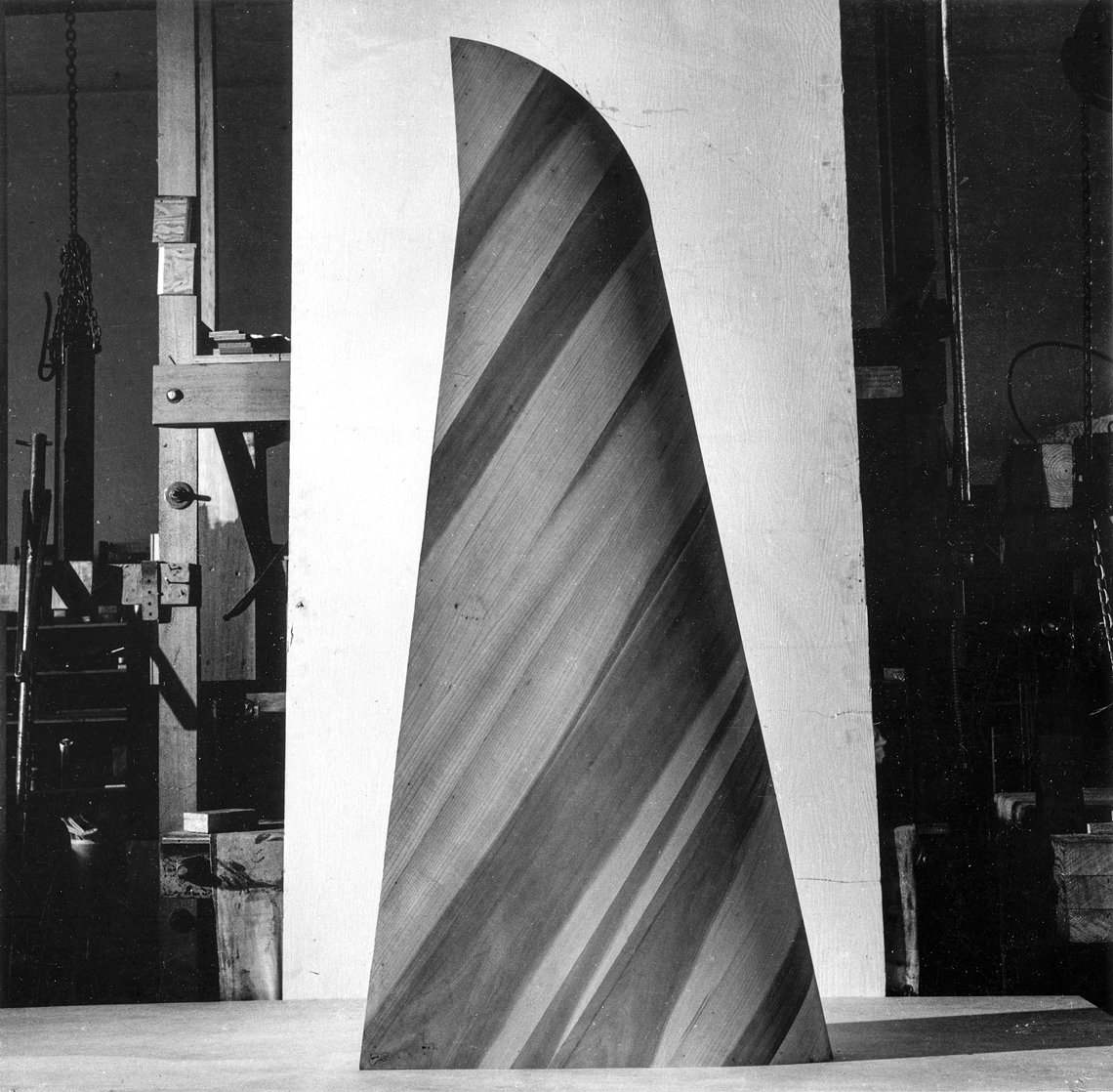

Charles and Ray Eames began experimenting with molding plywood as soon as they moved to California, with the aim of applying this process to furniture production. However, it was World War II that provided them with the opportunity to refine these techniques. After designing a new molded-wood leg splint for use on the front line, they formed the Molded Plywood Division of Evans Products Company in California, along with several friends and associates. They set up their workshop at 901 Washington Boulevard, the future home of the Eames Office. In 1943, the Eameses and their colleagues were contracted by the US Navy to develop parts for experimental military gilders. The stabilizer shown here was one of the aircraft parts produced for the Vultee BT15 Trainer. At the same time, the Eameses began a series of sculptural experiments in molded plywood, testing to what extremes the curves of the material could be pushed and using the natural grain of the wood to suggest undulating forms. The expressive possibilities of the medium can be seen in the stabilizer pictured here.

|

|

Ray Eames (1912–1988), Untitled, ca. 1939. Paint, ink, and crayon on paper. Eames Collections LLC. |

While living in New York in the 1930s, Ray Eames (née Kaiser) studied under the avant-garde artist Hans Hofmann, through whose classes she made friends with other artists, including Lee Krasner. The strong sense of form, structure, and color that Ray developed in her early drawings and paintings continued to define her artistic vision throughout her career — whether exploring the possible form of a chair, developing color palettes and textile designs for furniture, envisioning the design of an interior, or creating a children’s toy. During her years on the East Coast, Ray attended modern dance classes led by Martha Graham, and was a founding member of American Abstract Artists — a radical group that campaigned for the exhibition of nonrepresentational art. Her works from the late 1930s and early 1940s nod to a range of Modernist influences, from Cubism to Surrealism, while establishing their own particular form of biomorphic expression.

|

|

Plastic Stacking Chairs. © Eames Office LLC. |

By 1950, drawing on technical and material advances in plastics developed during World War II, the Eames Office had begun collaborating with Herman Miller, Inc. and Zenith Plastics to produce their most successful furniture design: the fibreglass-reinforced plastic chair. These lightweight molded plastic chairs were an immediate success, with several different base options offered. They could be easily stacked or connected in rows to make benches, making them ideal for schools, stadiums, and public spaces. The chairs were originally available in just three colors — greige, elephant-hide gray, and parchment. By 1963 they could be purchased in sixteen different colors and the range continued to expand. British architects Alison and Peter Smithson described the new chair designs being produced by the Eames Office as a ”message of hope from another planet,” in contrast to those available in Britain at the time.1

|

|

Eames House, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, Calif., 1949. Photograph by Julius Shulman. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10). |

Working at first with Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames was invited to design Case Study Houses Nos. 8 and 9 as part of Arts & Architecture magazine’s Case Study House program for modern homes. No. 8 was to become the Eameses’ house and studio, while No. 9 was intended for John Entenza, the editor of the magazine. Through the many issues of Arts & Architecture during 1949 and 1950, readers were kept abreast of the development of both projects. Harnessing new industrial processes, Charles and Ray Eames designed a frame made of prefabricated steel components, situated on an open meadow site in the Pacific Palisades. Thanks to the use of off-the-shelf parts, the house could be assembled at astonishing speed — the frame was apparently put together in a mere sixteen hours. The alternating use of colored panels and glass on the facade creates a syncopated composition, with striking effects of light and shade on the interior. Reflecting on the process of designing the house, Charles said, ”It’s like a game, building something out of found objects, which is the nicest kind of exercise you can do.” 2

|

|

Eames House, 1958. Photograph by Julius Shulman. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10). |

Conceived as a structure that could be adapted to the changing conditions of living and working, the Eameses’ house functioned as a backdrop for experimentation. The couple’s playful approach to design was epitomised in the way they used and adapted their own living spaces. It was at times treated as if a stage set, with changing installations of furniture, rugs, ornaments, artworks, toys, and artefacts — all arranged in precise configurations and installations. Ray even kept a log of the visitors to the house — they entertained a variety of guests, ranging from British architect Sir Hugh Casson, filmmaker Billy Wilder and his actress and model wife Audrey, and the students and nuns from the nearby Immaculate Heart College.

|

|

Tableau of The Toy and plywood children’s furniture set up at the Eames Office. © Eames Office LLC. |

In 1951, the Eames Office produced The Toy, a structural toy consisting of large square and triangular panels of bold colored, plastic-coated paper, wooden dowels, and wire connectors. With these basic components, users could create structures ranging from the simple to the fantastical. The Toy encouraged an open-ended attitude toward play, fundamental to the Eameses’ outlook. The product was not only aimed at children, but intended for teenagers and adults too, and the Eameses themselves used it as a backdrop for films, events in the Eames House, and photo shoots. They photographed different playful scenarios to advertise the product, from theatrical sets to tents and houses.

|

|

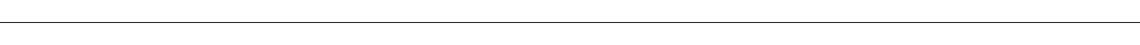

Lounge Chair and Ottoman photographed in the Eames House. © Eames Office LLC. |

In 1956, the Eameses launched their now iconic Lounge Chair and Ottoman with Herman Miller, Inc. It was a contemporary version of the traditional club chair. They chose to use luxurious woods and leather upholstery, although the basic design originated from the Eameses’ earlier experiments with mass production and standardized parts. Eames Office staff member Don Albinson worked closely with Charles and Ray Eames on developing the chair, which Charles hoped would have the “warm receptive look of a well-used first baseman’s mitt.” 3

|

|

Installation view of Glimpses of the U.S.A at the American National Exhibition, Moscow, 1959. © Eames Office LLC. |

In 1958, the Eames Office was invited to contribute to the American National Exhibition, a display of American products and technologies staged in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park in 1959. They conceived an immersive seven-screen, twelve-minute film Glimpses of the U.S.A., incorporating around two thousand images into a montage that communicated the experience of everyday life in America. Transmitted on a monumental scale, with an accompanying voiceover by Charles Eames and soundtrack composed by Elmer Bernstein, visitors were presented with varying scenes of America over the course of one day.

|

|

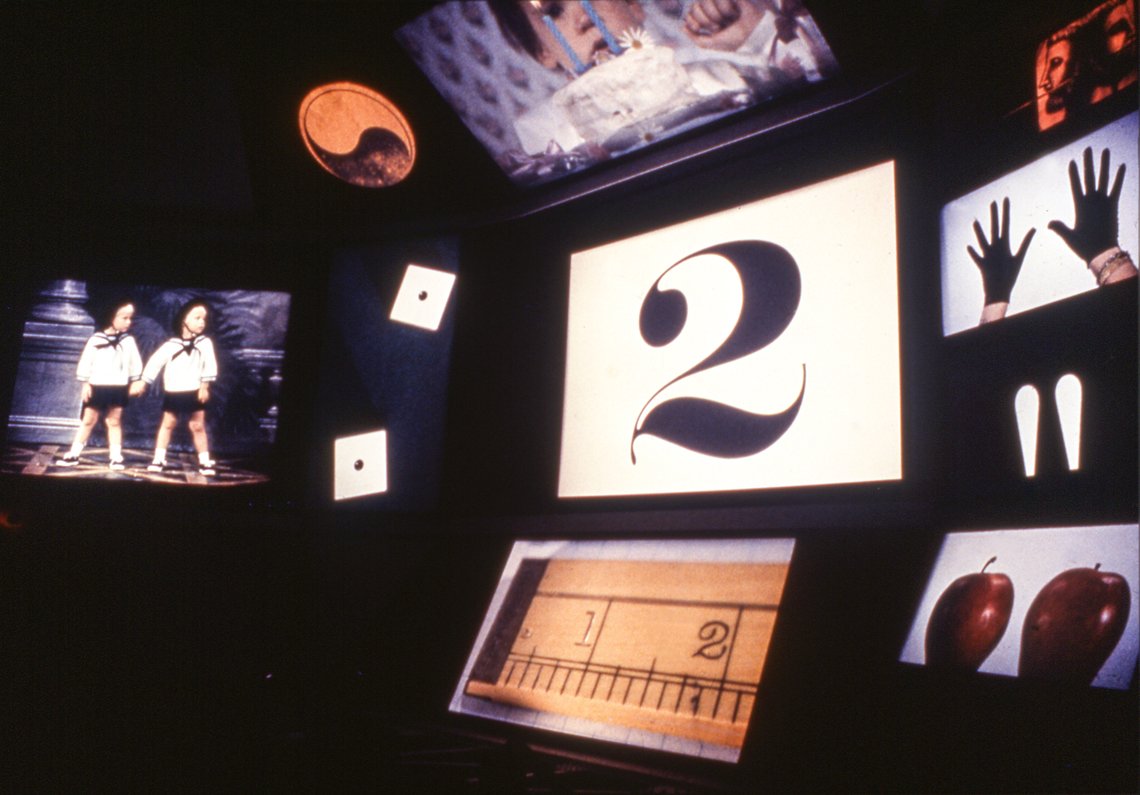

Installation view of Think, IBM Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, 1964–1965. © Eames Office LLC. |

Think was another pioneering multiscreen presentation made by the Eameses. This project was ahead of its time in terms of both its subject matter and its immersive installation, incorporating animated, still, and moving images across multiple screens to reveal how we approach both simple and complex issues with the same problem-solving techniques. The Eameses designed a huge ovoid-shaped theater on stilts to house the experience; visitors would make their way through a labyrinth of suspended walkways before taking a seat on the ”People Wall.” This was a huge tiered-seating structure, which whisked them up into the ovoid space, where the cinematic experience would begin. A variety of everyday scenarios were used to playfully communicate how information could be analyzed and visualized, including the planning of a dinner party and the operation of railroads.

|

|

View of the “Celestial Mechanics” device in Mathematica: A World of Numbers . . . and Beyond exhibition at the California Museum of Science and Industry, Los Angeles, 1961. © Eames Office LLC. |

The Eameses and their team designed many exhibitions throughout their lifetime. One of the most inspiring was Mathematica: A World of Numbers . . . and Beyond, initially conceived for the new wing at the California Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles in 1961. Taking Sir Isaac Newton’s ideas as their starting point, the Office worked with UCLA mathematics professor Raymond Redheffer to create interactive mechanical devices that helped to explain mathematical concepts with great humor and joy. Pictured here is “Celestial Mechanics,” in which a series of metal balls circle in mesmerising rings down a funnelled shape, illustrating the concept of elliptical orbits.

|

|

Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe, and the Effect of Adding Another Zero, 1977. Film, 9 mins. © Eames Office LLC. |

Now one of the Eameses’ most well-known films, Powers of Ten addresses “the relative size of things in the universe.” The film opens with the scene of a couple relaxing on a picnic rug near Lake Michigan in Chicago, then zooms into and out of space at intervals of increasing powers of ten. The result is a striking journey through the universe, expanding the viewer’s understanding of scale. Powers of Ten soon became a celebrated teaching tool and is still used in classrooms today. The Eameses understood both the increased knowledge as well as the potential danger that new surveillance technologies could bring. Charles commented: ‘It is interesting that most of the images in the last part of the film are of information that can be gathered by satellite. It is also interesting that this information — which is absolutely necessary to guard the health of our earth — is the same information that nations keep as secrets. What is most interesting is that the governments of the world will have to choose between their secrets and their planet earth.’ 4

|

The material shown in this article will be on display in The World of Charles and Ray Eames, on view at the Oakland Museum of California (museumca.org) through February 27, 2019. The exhibition takes its name from the sheer breadth of the Eameses’ practice. The Oakland Museum is the final venue of a three-year run and is a fitting end to the tour of the show considering that the Eameses moved to Los Angeles in 1941, living and working there for the remainder of their lives. The exhibit was curated and organized by Barbican Art Gallery, London.

|

Lotte Johnson is assistant curator at the Barbican Art Gallery, London.

|

1. Alison Smithson, “And Now Dhamas Are Dying Out in Japan,” Architectural Design, September 1966, 16–17.

|

2. Charles Eames, in Perry Miller Adato, dir., An Eames Celebration––Several Worlds of Charles and Ray Eames, 1973, 90 mins.

|

3. Pat Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century (MIT Press, 1995), 229.

|

4. Charles Eames, Notes on Powers of Ten, 1977. The Papers of Charles and Ray Eames, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.