Vive la France! The Enduring Elegance & Collectibility of Mid-Century French Design

|

Jean Royére “Ruban” coffee table. Iron, brass and Comblanchien limestone from the Côte-d'Or region of France. France, 1949. From Robert Stilin on Incollect.com and The Gallery at 200 Lex at the New York Design Center. |

|

The Enduring Elegance & Collectibility

of Mid-Century French Design

French designers have long led the market for collectible 20th-century design. Jean Prouvé, Jean Royère, Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier, and Charlotte Perriand are among the most recognizable names, along with Jacques Adnet, Pierre Chapo, and Pierre Guariche. This fame is justly deserved, for the variety, diversity, and inventiveness of much French mid-century design — along with attention to quality craftsmanship — is unparalleled in the 20th century.

| |

A vignette from Galerie André Hayat, Paris with pieces from Jean Royère: “Ondulaton” coffee table with red lacquered iron legs and red ceramic tile top. France, circa 1950s. Pair of “Petit Elephanteau” lounge chairs. Wool faux fur upholstery, oak legs. France, circa 1950s. “Millepatte” floor lamp, red lacquered wrought iron. France, circa 1950s. All from Galerie André Hayat on Incollect.com |

“French mid-century design is one of the market standards in the design world,” says Francis Milord, who has been dealing in French mid-century design for decades from his eponymous galleries in New York and Montreal. He credits extensive scholarship of the period along with the increasing scarcity of pieces as factors in the popularity. “There are lots of books and knowledge and research about these designers and the period, and the pieces are often numbered and dated, which helped build the market.”

Looking at auction records, it is clear that collectors are willing to pay a premium for pieces with an unassailable attribution and provenance. Royère’s signature ‘polar bear’ sofa and chair designs command over $1 million at auction — most recently in 2022 at Christie's in Paris where a polar bear sofa, circa 1947, sold for $1.5 million. It is just one of a dozen auction records in the Artnet price database at prices over $1 million for Royère’s signature furniture and lighting.

Royère items these days are rare and therefore have become especially expensive. He had a residual attachment to classical construction methods and as a consequence, many of his best designs were manufactured by hand and on a very small scale with the best materials available. There are fewer than 150 of his biomorphic polar bear sofas and chairs, according to the experts; the first pieces were designed in 1947 for the redecoration of his mother’s Parisian apartment. The polar bear series gets its nickname from their original lush white velvet covering.

What I love about the work of Jean Royere: of course it’s important, stylish, well made, and, while it’s unique in so many ways it also has a timelessness to it. But what I love most is that it has a sense of humor — it’s quirky — in the chicest way always!” — interior designer Robert Stilin |

Other major French mid-century designers have experienced ballooning auction prices, along with an increased demand for their work. Charlotte Perriand hit the $1 million mark at auction at Christie's, Paris, in 2021 for one of her consoles, a special order created for French music producer and club owner Bruno Coquatrix's Paris apartment in 1950. Prouvé is the overall auction leader among French mid-century designers — his designs for chairs and tables regularly sell at auction in the millions of dollars. At Sotheby's New York in 2021, a “S.A.M." table, from circa 1952, designed for the Air France Headquarters in Brazzaville, in the Congo, made of enameled steel and mahogany top, sold for $1,714,000.

Today’s bankable names of 20th-century design are not the only mid-century French designers of interest or historical importance. The attention showered on the top end of the market has obscured the accomplishments of many others like Pierre Chareau, René Gabriel, Paul Dupré-Lafon, Guillerme et Chambron, Joseph-André Motte, Antoine Philippon, Jacqueline Lecoq and Charles Dudouyt, to name a few. Dupré-Lafon was one of the most sought-after designers and decorators of the period and was popularly known as the ‘decorator to the millionaires’. He designed furnishings and interiors for the wealthy Dreyfus and Rothschild families.

|

Left: Charlotte Perriand “Sandoz” stool. Pine with distinctive chiseled-edge feet. France, circa 1960s. From Bloomberry on Incollect.com Right: Charlotte Perriand set of three low tripod stools in ash. France, circa 1950s. From Bloomberry on Incollect.com |

|

Charlotte Perriand set of six “Bauche” dining chairs. Wood with straw seats. France, circa 1950s. From Goldwood by Boris on Incollect.com |

|

Left: Charlotte Perriand “Cansado” sideboard. Mahogany with lacquered laminate sliding doors, steel base. France, circa 1958. From Pavilion Antiques and 20thc on Incollect.com Right: Charlotte Perriand “Forme Libre” coffee table. Three legs, freeform top, oak. France, circa 1958. From Kerry Joyce Atelier on Incollect.com |

Dupré-Lafon’s aesthetic is affiliated stylistically with Art Deco, which preceded mid-century modern design in France and continued to exercise an influence over designers into the postwar period. Whereas French Art Deco privileged exquisite craftsmanship, expensive materials, and decorative excess, mid-century French design takes inspiration from the modern world. The underlying ethos was one of clean-lined, direct, affordable furniture made to be used, with minimal and unadorned forms often created with untreated wood or semi-industrial materials like steel, plywood, Formica, and aluminum.

-12.jpg) | |

Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand, “LC3” armchair for Cassina. Chrome-plated steel frame, Italian white leather. Italy, circa 1990s. From Goldwood by Boris on Incollect.com |

Mid-century French design was as much a reaction against the preciousness and exclusivity of Art Deco as a direct response to the changing social needs of the time and a new emerging consumer culture. French mid-century designers also paid attention to technology and the possibilities of machines and mass production to reproduce designs for a broader market. Prouvé in particular researched and later harnessed the power of factory assembly lines to create mass-produced furniture for public spaces including colleges, public housing, and administrative and government institutions.

| |

Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Charlotte Perriand, “LC4” lounge chair. Adjustable chrome-plated steel frame, beige canvas, ponyskin, leather. Italy, 1965. Photo courtesy Goldwood by Boris. |

While several mid-century French designers aspired to see their designs go into mass production (including Jeanneret and Perriand) there also remained paradoxically a commitment to craftsmanship, frequently in the form of a close collaboration between artists, designers, and skilled craftsmen — a quality that today is widely appreciated in French design from the period. French mid-century design is also characterized by inventive material combinations, such as steel plates cased in stitched leather or light fixtures made of metal mixed with raw stone. There is, overall, in French design from this era a beguiling tension between formal elegance and raw materiality.

One of the great figures of the modern movement in French design was Swiss-born architect and designer Le Corbusier, who, beginning in the 1920s, created a line of modern furniture designs that he described as ‘equipment for living’ and that he believed would replace all existing home furnishings. Le Corbusier was a brilliant and forward-thinking figure in 20th-century French design, credited with embracing technology and machine-age materials. Today his designs are modern classics, including his chromed tubular steel LC4 chaise lounge, his LC1 and LC2 chairs, and his LC3 armchair and sofa designs.

|

Pierre Jeanneret “Easy” pair of armchairs, model PJ-S1-32-A. Teak, leather upholstery. Chandigarh, India, circa 1958–1959. From JF Chen on Incollect.com |

| |

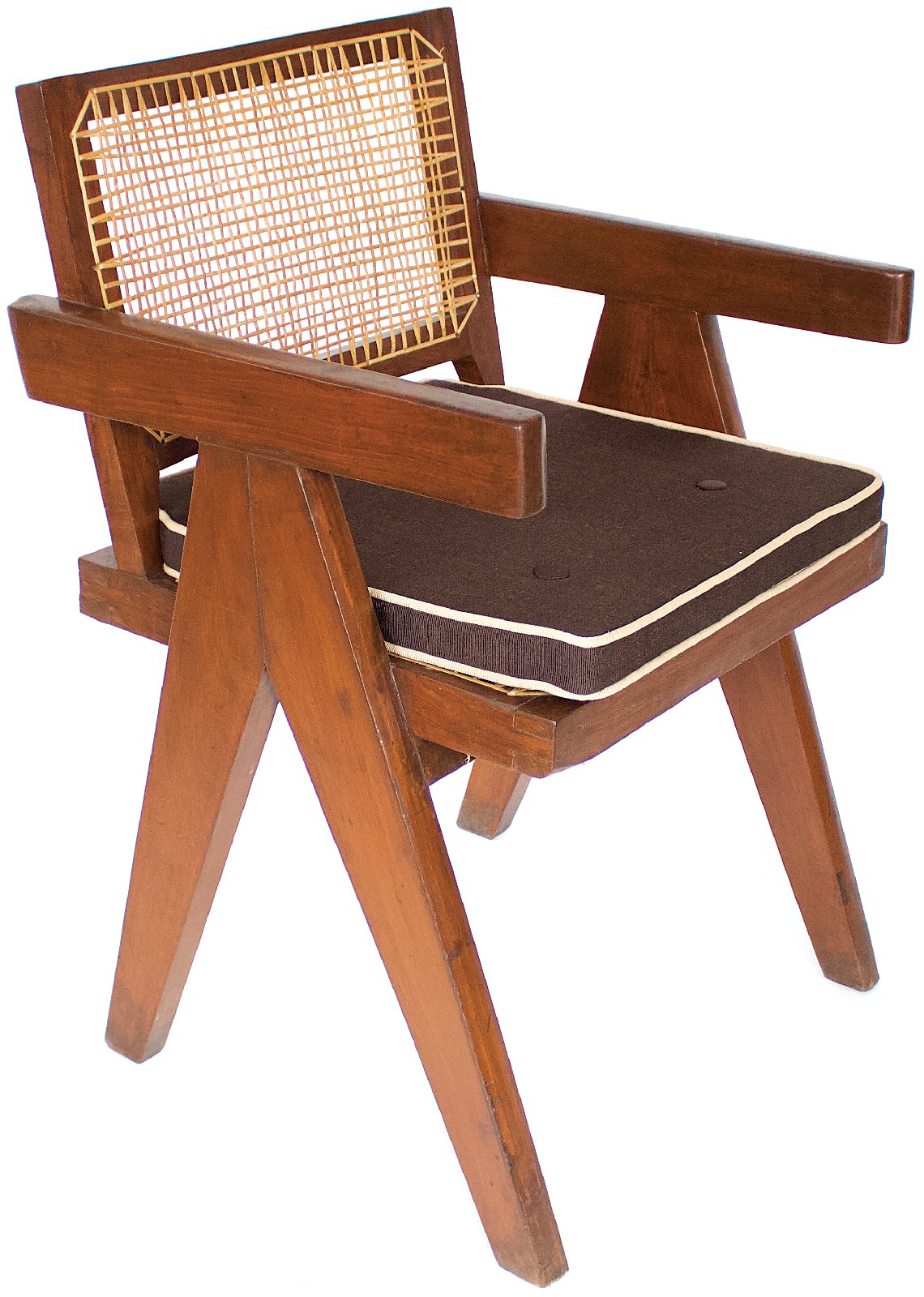

Pierre Jeanneret “Office” armchair, model PJ-SI-28-B. Teak frame, restored cane seat and back, new cushion. Chandigarh, India, circa 1956. From Pavilion Antiques and 20thc on Incollect.com |

Scholars have since determined that it was actually Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret who came up with many of the designs for furniture attributed to Le Corbusier, or at least the designs were made as part of a collaboration. Perriand went to work in his offices in 1927, at the age of 24, and brought new ideas and a nascent vision of the needs of everyday people in an emerging modern world. Her designs for Le Corbusier are characterized by elemental forms made of industrial materials. Later she was to shift her design focus somewhat and embrace nature and natural materials, inspired by Japanese aesthetics following an invitation to travel to Japan in 1940.

Jeanneret is one of the most popular and collectible designers of the modern movement in France. He was a Swiss architect, like his cousin Le Corbusier and the two began an architecture practice in Paris in 1922. Together they designed numerous modern architectural icons, the most famous being the plan and much of the built architecture for the utopian new town of Chandigarh, India. He designed furniture for Chandigarh as well, like his iconic 1950s ‘Office’ chair for the administrative buildings of Chandigarh made of recycled local wood with legs shaped like a compass and the seat and floating backrest of woven cane.

Jeanneret also collaborated extensively with Charlotte Perriand and the pair, who were lovers for a time, even teamed up with Jean Prouvé in 1940 to research prefabricated housing. Prouvé was a metal worker with no formal training in either design or architecture, but throughout his career, he designed everything from bicycles and furniture to student housing and even a new kind of stove. He was inspired by the possibilities of industrial materials, methods and processes, and how they could be applied to standardized, mass-produced design. He designed portable barracks for the army and prefabricated steel, cheap demountable vacation homes for workers.

|

Jean Prouvé “Flavigny” daybed with swivelling tablet designed by Charlotte Perriand. Black lacquered metal frame, wood, oak tablet, black canvas-covered cushion. France, circa 1950s. From Goldwood by Boris on Incollect.com |

Prouvé’s signature furniture often employs sheet metal, mostly steel and aluminum that was bent, pressed, compressed, and then welded, as opposed to the steel tubing that was favored by Le Corbusier and of course the Bauhaus designers. Sheet metal was not only stronger, but it could also be manipulated into almost any shape or form and therefore in addition to Prouvé proved very popular with other French mid-century designers including Jacques Adnet, whose simple modern forms with clean lines were often rendered in welded metal wrapped in luxurious hand-stitched leather. His designs bridge the gap between Art Deco and modernism and today remain highly prized by collectors for their simplicity and elegance.

|

| Upper grouping — Left: Paul Duprè-Lafon credenza. Goatskin, red leather and lacquered ebonized wood cabinet with bronze moldings and drawer pulls. France, circa 1950. From Milord Antiques on Incollect.com and The Gallery at 200 Lex at the New York Design Center. Right: Paul Duprè-Lafon for Hermès floor lamp. Beechwood, leather, and metal. France, circa 1950. From Milord Antiques on Incollect.com and The Gallery at 200 Lex at the New York Design Center. |

|

| Top left: Pierre Guariche “Courchevel” lounge chair for Sièges Témoins. Chromed steel frame, new light grey velvet upholstery from the Kvadrat Raf Simons collection. France, circa 1959. From Jasper Maison on Incollect.com Top right: Pierre Guariche “Cerf-volant” floor lamp. Gilded brass shaft, black lacquered metal bulb cover and feet, white lacquered sheet metal reflector. France, 1952. From Galerie Canavèse on Incollect.com Bottom: Pierre Guariche for Steiner, pair of SK660 armchairs with footstools. Tubular black lacquered metal legs and wooden frame, foam-filled and reupholstered with Nobilis wool bouclé. France, 1953. From Jasper Maison on Incollect.com |

Pierre Chareau, another important French designer, was one of the first to show interest in the use of steel and iron for furniture and lighting manufacture. Among his best-known designs is his “T 1927” model stools made of painted steel with wood veneered tops, along with innovative sconces combining blocky alabaster panels suspended in a steel metal armature. He also designed iron-framed chairs with woven cane seats which are somewhat rare and highly prized by collectors. Chareau, an architect and designer, built France's first house made entirely of steel and glass called Maison de Verre.

| |

Serge Mouille original vintage sconce. Hand-hammered, black lacquer with brass details, adjustable shade and arm. France, circa 1958. From Conjeaud & Chappey on Incollect.com |

Sheet steel was used by other mid-century French designers, among them Pierre Guariche and Serge Mouille. Guariche was a versatile and flamboyant designer who created the “Tonneau” chair, the first molded plywood chair (with black enameled iron tubing legs) mass-manufactured by Steiner in the 1950s. Today it is a modern design icon along with his sheet metal luminaires, which often feature design details like hidden light sources, perforated metal surfaces, and slender leg structures. The models “G30”, “G21” and “G1” are sculptural floor lamps on circular or triangular tripod lacquered metal bases topped with variously curved, lacquered, and perforated sheet metal reflectors that diffuse and give off a soft filtered ambient light. Mouille studied metallurgy and graduated in silversmithing, and in the 1950s began designing versatile, functional light fixtures and lamps. Always sculptural in design, they were made of various metals with pivoting arms and swiveling shades.

René Gabriel lounge chair. Black lacquered frame, grid back, bouclé upholstered cushions. France, circa 1950s-60s. From Galerie André Hayat on Incollect.com |

René Gabriel was another mid-century French designer who toyed with geometry. Gabriel created many memorable designs, most famously for lounge or club chairs, often with sharply angled arms attached to a gridded seat and backrest supports. His chair designs embody modern aesthetics in a pure unadulterated form — elegantly simple and functional.

Pierre Chapo also sought radical simplicity in his designs as well as in the construction of his furniture. Chapo was a master woodworker, working mainly with oak, ash, and solid elm wood. His forms are direct and industrial in appearance and have often been associated with Brutalist design. He was focused on proportion, scale, balance, and hand craftsmanship, allowing the natural wood to dictate some of the decision-making as to the final shape and form. He was more a maker than a designer and should be compared properly to George Nakashima and other studio woodcraft artists.

|

René Gabriel rare carved back armchairs. Solid oak with unusual geometric carved back. France, circa 1960s. From Galerie André Hayat on Incollect.com |

|

Pierre Chapo “T21” dining table and “S34” dining chairs. Distinctive crossed-leg base in the designer’s favorite wood, the now-extinct French elm. France, circa 1960–1970s. From Goldwood by Boris on Incollect.com |

|

Pierre Chapo “T22 L’oeil” coffee table. Two arch-shaped tables with center “eye” attached to one piece. Solid elm. France, circa 1970s. From H. Gallery on Incollect.com |

Guillerme et Chambron, the design team of designers Robert Guillerme and Jacques Chambron, formed the company Votre Maison in 1949 after they partnered with Émile Dariosecq, a French woodworker and shop owner. Together they produced beautiful, functional wood furniture like their famous high-back “Repos” lounge chair with long wooden spindles, lightly curved reaching upward like fingers atop carved solid wood armrests and carved wood legs. Elegant simplicity is again the guiding aesthetic sensibility, with attention to detail and finish.

|

Guillerme et Chambron set of “Grand Repos” lounge chairs. Light oak with curved spindle back. France, circa 1950s. From H. Gallery on Incollect.com |

|

Guillerme et Chambron round tables with ceramic tile tops. Left: Stanislas Model, light oak with 16 ceramic tiles, 37" diameter, adjustable height from 21" to 29" for use as a coffee table or dining table. Right: Light oak coffee table with six ceramic tiles, 27" diameter. France, circa 1960s. From Appel on Incollect.com |

|

| Charles Dudouyt “Circle” Sideboard. Oak with intricately carved circle pattern on doors and base. France, circa 1940s. From Orange Los Angeles on Incollect.com |

Though lesser known in the American collectible design world than some other mid-century French designers, Guillerme et Chambron created designs that have proven timeless. Much of their work has a contemporary look and feel, mixing easily into any interior. “Everything turns in the world of taste,” says dealer Eric Appel, long an admirer and avid collector of Guillerme et Chambron. “Things look right at a certain moment in time. But a lot of French mid-century design has never gone out of style. This is hard to say about other designers of the 20th century.”