Winterthur Primer: Fakes, Forgeries, and the Art of Detection

|

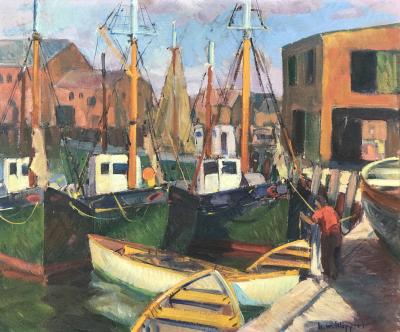

| Fig. 1:Wreck on Doughnut Point. Watercolor in the style of Andrew Wyeth, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy of David Hall. |

F

ortunately, most people are not driven to defraud others. There will always be, however, individuals who, whether for financial gain or egotistical thrill, will deceive people through fraud or forgery.1

While there are instances when a quality reproduction will pass through several owners and be separated from its date of manufacture, there are other occasions when an object’s origin story and maker’s intent is a bit more suspect. Such was the case of a watercolor purportedly by Andrew Wyeth (1917−2009), and consigned for auction in 1998 (Fig. 1). Before the sale, the painting was sent to Wyeth who identified it as a forgery. The same watercolor remained on the market and reappeared in 2000. Consigned to a different auction house in 2008, it was again sent for authentication. Mary Landa, the Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection Manager, immediately recognized it as the same copy of a genuine watercolor in a private collection that she and Wyeth had seen a decade earlier. Concerned that the painting would continue to circulate on the market, Landa contacted the FBI, who confiscated the work in 2009. The intention of the various owners who sold and resold this watercolor is unknown, but the originator was certainly aware it was a fake. The lesson? Work with professionals you trust and who are willing to ask questions.

“You’ve shown me your masterpieces,

now show me your fakes.”

— Henry Francis du Pont to a fellow collector

Unfortunately, the authenticity of works of art cannot always be definitively confirmed. Figure 2, for instance, is an oil on board painting signed “HOMER”; the painting was purchased fifty years ago at a small auction house in northern Virginia. The work is compositionally similar to a genuine work entitled High Cliff, Coast of Maine, which was painted in 1894 and depicts the view from Winslow Homer’s home and studio on Prout’s Neck in Scarborough, Maine. Differences from Homer’s normal practice include the fact that the work was painted on a cross-laminate board and not canvas and it was quickly and thinly painted, with no attempt to delineate texture of the rocks or the water. Examination of the signature, however, reveals it is contemporary with the painting, and scientific analysis shows that all the pigments are appropriate for the 1890s. In addition, a canvas portrait that was once adhered, face down, to the back of the board depicts an elderly man who bears a striking resemblance to one of Homer’s favorite models, John Gatchell (Fig. 3). Could this mystery painting be a preliminary version, or sketch, of the more famous work that never made it into the catalogue raisonné? The jury is still out, but this case shows how difficult the authentication of art and antiques can sometimes be. The lesson? Use the evidence presented, consult experts (which includes art historians, curators, dealers and auctioneers), and work with people you trust. If a mistake is made, a reputable individual or company will handle the situation professionally; check policies prior to purchase.

|  | |

| Fig. 2: Untitled seascape, artist unknown, 19th century Oil on cross-laminate veneer panel, 31 x 37 inches (framed) Collection of W. Brown Morton | Fig. 3: Untitled portrait, artist unknown, 19th century Oil on canvas, 29-5/8 x 35-5/8 inches Collection of W. Brown Morton |

New methods of researching provenances, new insights into materials and techniques used to create works of art, and new tools for scientific analysis are constantly being developed and published—but the technical skills employed to create fakes and forgeries are also constantly improving. It is important to have an open and enquiring mind because many, if not most, public and private collections likely contain questionable objects. To learn about case studies involving fakes and forgeries, in areas ranging from baseball memorabilia to fashion and decorative and fine arts, and about the authentication and discovery process, visit Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes, on display at Winterthur Museum through January 7, 2018. For more information visit www.winterthur.org.

Linda Eaton is the John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, Winterthur, Delaware. Colette Loll is the founder and president of Art Fraud Insights. Together they curated the exhibition Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. They are also gathered together at www.Winterthur.org.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.