Winterthur Primer: Nothing to Sneeze At: Commemorative Handkerchiefs for the American Market

Printed handkerchiefs of all kinds have long been popular with collectors. Historically, the term “handkerchief” can mean a utilitarian piece of fabric used to wipe the eyes, nose, or brow, or a decorative accessory carried in the hand, dangled from a pocket, worn around the neck, or sometimes covering the head. So-called “handkerchiefs” were also often stitched into the center of quilts. Today, historic handkerchiefs are most often framed and hung on a wall.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, handkerchiefs were a mainstay of many textile printers’ production. Records show that block printers had special sized tables on which to print them, while in the nineteenth century, sizes of handkerchiefs were adapted to the limitations of the roller printing machines. Today, collectors focus primarily on iconography, but another way to consider them is by maker. Although the vast majority of surviving examples are anonymous, a few early examples can be documented and safely attributed to textile printers in London, Glasgow, and Philadelphia.

London was an early center of textile printing and even after the bulk of the industry moved north, printers in London continued to produce handkerchiefs and shawls into the twentieth century for the high end of the market. Although many firms are known to have printed handkerchiefs, the work of only a few can be documented (Fig 1). Among them is Henry Gardiner (1744–1839), whose printworks in Wandsworth, Surrey, employed 250 hands in the early 1790s. Gardiner inscribed his name on some of his prints, including an allegorical “Map of Man” and yardage printed for use as furnishings.1

It might seem odd that British textile printers would celebrate the American general who had recently defeated the might of the British army, but at the time of the American Revolution, the colonies in North America were the fastest growing and wealthiest market for British goods. Although many London merchants had been bankrupted by the disruption in trade during the war, the American market remained important to the calico printing industry.

During the Revolution, merchants in the southwest of Scotland began to invest heavily in various branches of cotton manufacturing and continued to export their goods to America after peace was achieved. Winterthur’s collection includes a very rare early handkerchief printed by William Gillespie & Company commemorating the resignation of George Washington from the presidency of the United States in 1796 (Fig 2). William Gillespie (d. 1807) operated a large and successful business spinning, weaving, and printing cotton in the Glasgow area. He first established a printworks at Anderston in about 1772, which was later enlarged by his son Richard. Winterthur has a handkerchief printed by “R. Gillespie, Anderston Printfield, Near Glasgow” in about 1815.2 The American trade was so important that another son, Colin, lived in New York (and became an American citizen), in the 1790s and the early 1800s. When Colin Gillespie returned to live in Scotland in 1805 he established a partnership with John Graham, who ran the American side of the business.3

Handkerchiefs were also part of the stock-in-trade of American calico printers. John Hewson (1744–1821), although not the first, was one of the most successful early calico printers in America. John Sr. founded the firm in 1774; in 1793 he gave Martha Washington a “piece of elegant Chintz” printed by him in the hope that she would wear it to remove the prejudice against American manufactures, which were generally believed to be of lower quality than those imported from Britain. A handkerchief celebrating George Washington as the “Protector and Foundator [sic] of America’s Liberty and Independency” has been attributed to Hewson, although there were other calico printers active in Philadelphia at the time who could also have printed it (Fig 3).4

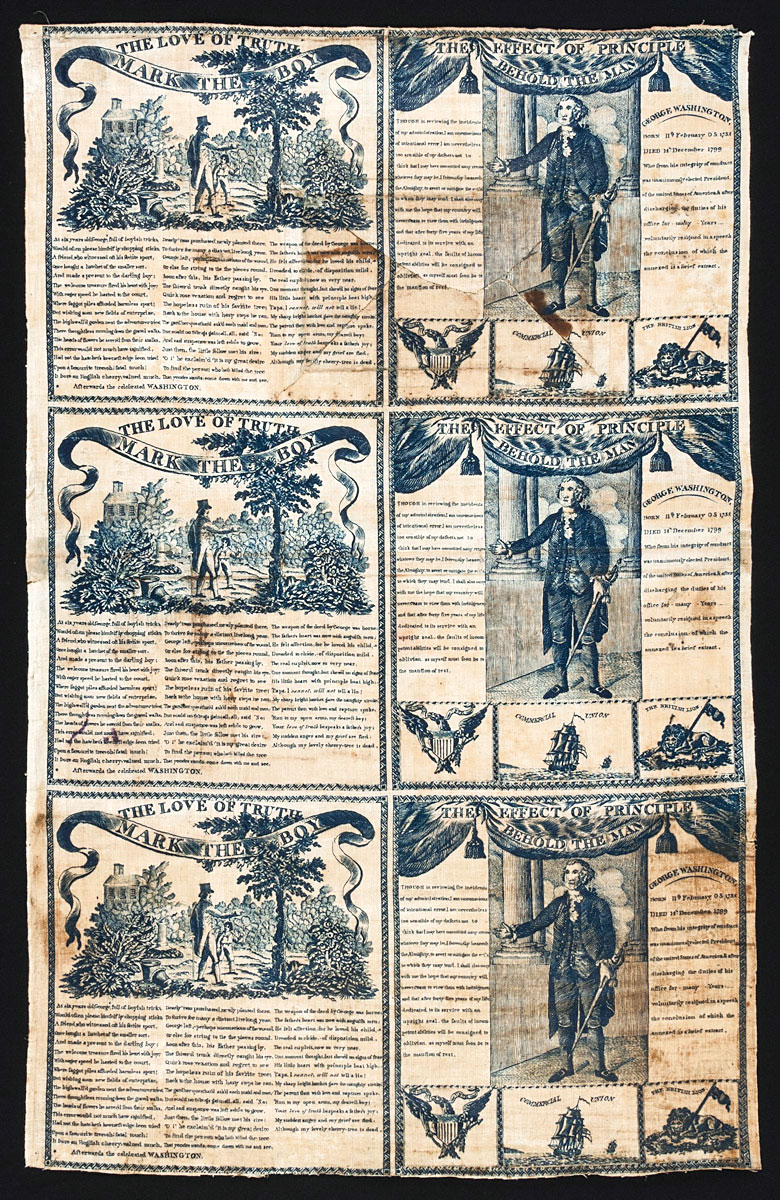

The Hewsons were block printers, and we can speculate that one of the reasons that John Jr. might have discontinued the business in the 1820s was because he could not compete with the new technology of printing with engraved rollers. In 1808, a block printer could produce 224 yards a day compared to 5,600 yards from a roller printing machine, which brought prices down considerably.5 The printworks of Thorpe, Siddall & Company in Germantown, Pennsylvania, claimed to be the first to use this new technology in America in 1809.6 A set of uncut handkerchiefs attributed to Germantown Printworks, which might be how Thorpe, Siddall & Co was publicly known, commemorates George Washington in the form of small pocket handkerchiefs for children (Fig 4). A handkerchief commemorating the visit of Lafayette to Philadelphia in 1824 is also inscribed “Germantown Printworks.” Frustratingly, there were a number of other Germantown calico printers in the 1820s, including Lindley’s (in operation by the early 1830s) and the firm owned by William Logan Fisher and his son-in-law William Wister.7 The quest to positively identify the Germantown Printworks continues and the author would be grateful for any clues that readers might provide (leaton@winterthur.org).

-----

Linda Eaton is the John L. & Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections & Senior Curator of Textiles at Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. They are also gathered together at www.Winterthur.org.

This article was originally published in the 16th Anniversary (Spring 2016) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a ditigized version of which is available on www.afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and afamag are affiliated with InCollect.

2. Winterthur accession number 1959.967. For more information about this handkerchief see Diane DeBlois, “Postal History You Can Wear: U.S. Rates and Routes Bandana From 1815.” The Chronicle of the U.S. Classic Postal Issues 67, no. 2 (May 2015): 151–154, and Winterthur’s online collection database.

3. Colin Gillespie appears in a court case in which he claimed that cargo from a ship captured by American privateers should not be confiscated. See The Federal Cases: Comprising Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Federal Reporter, Arranged Alphabetically by the Titles of the Cases and Numbered Consecutively, Book 9 (St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1895) Case Number 5,034.

4. John Monsky “From the Collection: Finding America In Its First Political Textiles.” Winterthur Portfolio 37, no. 4 (Winterthur 2002): 239–264.

5. Chapman and Chassagne, European Textile Printers in the Eighteenth Century: A Study of Peel and Oberkampf (London: Heinemann Books, 1981), 43–44.

6. See Philip Scranton, Proprietary Capitalism: The Textile Manufactures at Philadelphia, 1800–1885 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 109.

7. For a discussion of printworks in Germantown, see Linda Eaton, Printed Textiles: British and American Cottons and Linens 1700–1850 (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2014), 81–101.