Norman Rockwell

American, 1894 - 1978

Mr. Rockwell began his illustrious career with immediate success when he painted Christmas cards, for his first commission, at age sixteen, and illustrated his first book one year later. Aglow with success, the determined young man signed his name in blood, swearing never to do advertising jobs. He kept that promise until his first known advertisement for H. J. Heinz Company, Pork'n Beans, appeared in the 1914 edition of the Boy Scout Handbook. The first advertisement by Norman Rockwell to appear in The Saturday Evening Post was January 13, 1917. His first Post cover was published on May 20, 1916.

Much of Rockwell's prodigious output was painted for magazine reproduction and never intended to provide enduring examples of his work. Due to his own technique of using a special compound between layers of paint, some of his originals have yellowed with age, but the aging hasn't diminished his popularity nor the demand for "anything Rockwell." After many years of being scorned as an unworthy imitator, Norman Rockwell's human interpretation of the American scene survived the criticism of art connoisseurs. His work was revered, year after year on magazine covers by two generations of Rockwell watchers: Those who recalled and those too young to remember.

Perhaps the most provocative opinion on Rockwell's work was expressed in a November 13,1970 issue of Life Magazine. When the editors brought the dilemma of Rockwell's art popularity and lack of recognition, to their reading public in a one page article, posing the question: "If We All Like It Is It Art?" Their readers promptly responded.

The resulting action from ordinary people around the world created the first -man art revolution in America, far surpassing Currier and Ives. A few months later, the first Norman Rockwell plate, The Family Tree, was fired; the Rockwell Revolution had started, and the first of millions of collectibles were offered to Rockwell loving minions. It was then that author, Thomas Buechner and publisher, Harry Abrams moved Rockwell out of the closet, and onto the world's coffee tables. The rest is art history.

Much of Rockwell's prodigious output was painted for magazine reproduction and never intended to provide enduring examples of his work. Due to his own technique of using a special compound between layers of paint, some of his originals have yellowed with age, but the aging hasn't diminished his popularity nor the demand for "anything Rockwell." After many years of being scorned as an unworthy imitator, Norman Rockwell's human interpretation of the American scene survived the criticism of art connoisseurs. His work was revered, year after year on magazine covers by two generations of Rockwell watchers: Those who recalled and those too young to remember.

Perhaps the most provocative opinion on Rockwell's work was expressed in a November 13,1970 issue of Life Magazine. When the editors brought the dilemma of Rockwell's art popularity and lack of recognition, to their reading public in a one page article, posing the question: "If We All Like It Is It Art?" Their readers promptly responded.

The resulting action from ordinary people around the world created the first -man art revolution in America, far surpassing Currier and Ives. A few months later, the first Norman Rockwell plate, The Family Tree, was fired; the Rockwell Revolution had started, and the first of millions of collectibles were offered to Rockwell loving minions. It was then that author, Thomas Buechner and publisher, Harry Abrams moved Rockwell out of the closet, and onto the world's coffee tables. The rest is art history.

Norman Rockwell is perhaps the greatest American illustrator. He created countless scenes of proud family values and humorous subjects with just the right expressions or posture that tell a story instantly. Rockwell studied at the Chase Art School c.1908, The National Academy of Design (1909) and the Art Students League (1916) as well as being awarded three honorary degrees from other colleges. By the age of 18, Rockwell worked as the art director for the magazine Boys Life. He sold his first five covers to the editor of the Saturday Evening Post when he was only 22. At that point, Rockwell averaged 10 covers per year. He began with a small sketch, then made individual drawings of each element in the scene and finally created a full sized charcoal drawing of the entire scene before producing the painting. Rockwell produced over 322 covers for the Saturday Evening Post from 1916-63. His work was used in Brown & Bigelow Calendars from 1924-76 as well as every major magazine. Rockwell's illustrations for Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn are classics. Later in his career Rockwell used photography to project images onto his canvases. From 1960 until his death, Rockwell spent most of his time on large painted photomontages of contemporary personages and events. He died in 1978.

Biography courtesy of The Caldwell Gallery, www.antiquesandfineart.com/caldwell

Biography courtesy of The Caldwell Gallery, www.antiquesandfineart.com/caldwell

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. At age 14, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at The New York School of Art (formerly The Chase School of Art). Two years later, in 1910, he left high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty's instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career.

Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he was hired as art director of Boys' Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a variety of young people's publications.

Portrait of Rockwell as a young artist

Photo by McManus Studios, New York City

At age 21, Rockwell's family moved to New Rochelle, New York, a community whose residents included such famous illustrators as J.C. and Frank Leyendecker and Howard Chandler Christy. There, Rockwell set up a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe and produced work for such magazines as Life, Literary Digest, and Country Gentleman. In 1916, the 22-year-old Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine considered by Rockwell to be the "greatest show window in America." Over the next 47 years, another 321 Rockwell covers would appear on the cover of the Post. Also in 1916, Rockwell married Irene O'Connor; they divorced in 1930.

The 1930s and 1940s are generally considered to be the most fruitful decades of Rockwell's career. In 1930 he married Mary Barstow, a schoolteacher, and the couple had three sons, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter. The family moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939, and Rockwell's work began to reflect small-town American life.

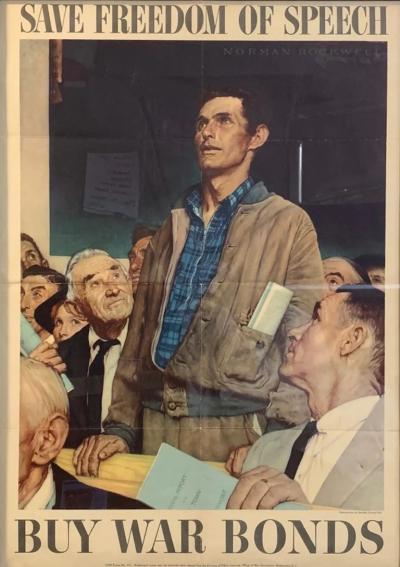

In 1943, inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt's address to Congress, Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms paintings. They were reproduced in four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post with essays by contemporary writers. Rockwell's interpretations of Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear proved to be enormously popular. The works toured the United States in an exhibition that was jointly sponsored by the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department and, through the sale of war bonds, raised more than $130 million for the war effort.

Although the Four Freedoms series was a great success, 1943 also brought Rockwell an enormous loss. A fire destroyed his Arlington studio as well as numerous paintings and his collection of historical costumes and props.

Norman Rockwell surrounded by studies for his 1955 painting The Art Critic

Photo by Bill Scovill

In 1953, the Rockwell family moved from Arlington, Vermont, to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Six years later, Mary Barstow Rockwell died unexpectedly. In collaboration with his son Thomas, Rockwell published his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, in 1960. The Saturday Evening Post carried excerpts from the best-selling book in eight consecutive issues, with Rockwell's Triple Self-Portrait on the cover of the first.

In 1961, Rockwell married Molly Punderson, a retired teacher. Two years later, he ended his 47-year association with The Saturday Evening Post and began to work for Look magazine. During his 10-year association with Look, Rockwell painted pictures illustrating some of his deepest concerns and interests, including civil rights, America's war on poverty, and the exploration of space.

In 1973, Rockwell established a trust to preserve his artistic legacy by placing his works in the custodianship of the Old Corner House Stockbridge Historical Society, later to become the Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge. The trust now forms the core of the Museum's permanent collections. In 1976, in failing health, Rockwell became concerned about the future of his studio. He arranged to have his studio and its contents added to the trust. In 1977, Rockwell received the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, for his "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country." He died at his home in Stockbridge on November 8, 1978, at the age of 84.

Biography courtesy of Roughton Galleries, www.antiquesandfineart.com/roughton

Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he was hired as art director of Boys' Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a variety of young people's publications.

Portrait of Rockwell as a young artist

Photo by McManus Studios, New York City

At age 21, Rockwell's family moved to New Rochelle, New York, a community whose residents included such famous illustrators as J.C. and Frank Leyendecker and Howard Chandler Christy. There, Rockwell set up a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe and produced work for such magazines as Life, Literary Digest, and Country Gentleman. In 1916, the 22-year-old Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine considered by Rockwell to be the "greatest show window in America." Over the next 47 years, another 321 Rockwell covers would appear on the cover of the Post. Also in 1916, Rockwell married Irene O'Connor; they divorced in 1930.

The 1930s and 1940s are generally considered to be the most fruitful decades of Rockwell's career. In 1930 he married Mary Barstow, a schoolteacher, and the couple had three sons, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter. The family moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939, and Rockwell's work began to reflect small-town American life.

In 1943, inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt's address to Congress, Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms paintings. They were reproduced in four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post with essays by contemporary writers. Rockwell's interpretations of Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear proved to be enormously popular. The works toured the United States in an exhibition that was jointly sponsored by the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department and, through the sale of war bonds, raised more than $130 million for the war effort.

Although the Four Freedoms series was a great success, 1943 also brought Rockwell an enormous loss. A fire destroyed his Arlington studio as well as numerous paintings and his collection of historical costumes and props.

Norman Rockwell surrounded by studies for his 1955 painting The Art Critic

Photo by Bill Scovill

In 1953, the Rockwell family moved from Arlington, Vermont, to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Six years later, Mary Barstow Rockwell died unexpectedly. In collaboration with his son Thomas, Rockwell published his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, in 1960. The Saturday Evening Post carried excerpts from the best-selling book in eight consecutive issues, with Rockwell's Triple Self-Portrait on the cover of the first.

In 1961, Rockwell married Molly Punderson, a retired teacher. Two years later, he ended his 47-year association with The Saturday Evening Post and began to work for Look magazine. During his 10-year association with Look, Rockwell painted pictures illustrating some of his deepest concerns and interests, including civil rights, America's war on poverty, and the exploration of space.

In 1973, Rockwell established a trust to preserve his artistic legacy by placing his works in the custodianship of the Old Corner House Stockbridge Historical Society, later to become the Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge. The trust now forms the core of the Museum's permanent collections. In 1976, in failing health, Rockwell became concerned about the future of his studio. He arranged to have his studio and its contents added to the trust. In 1977, Rockwell received the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, for his "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country." He died at his home in Stockbridge on November 8, 1978, at the age of 84.

Biography courtesy of Roughton Galleries, www.antiquesandfineart.com/roughton

Norman Rockwell

"Save Freedom of Speech. Buy War Bonds" Vintage WWII Poster by Norman Rockwell

H 31 in W 23 in D 1 in

Norman Rockwell

"Ours to Fight for Freedom from Fear" Vintage WWII Poster by Norman Rockwell

H 42 in W 31 in D 1 in

Loading...

Loading...