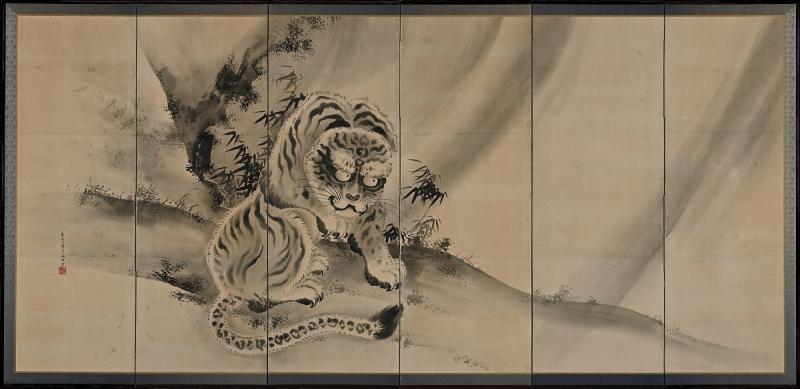

19th Century Japanese Screen Pair. Tiger & Dragon by Tani Bunchu.

-

Description

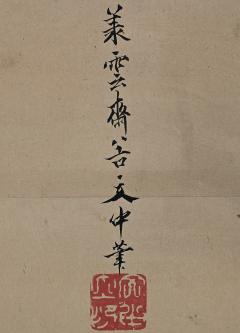

Tani Bunchu (1823-1876)

Tiger and Dragon

A pair of six-panel Japanese screens. Ink on paper.

Dimensions: Each Screen: H. 179 cm x W. 366 cm

Price: USD 32,000

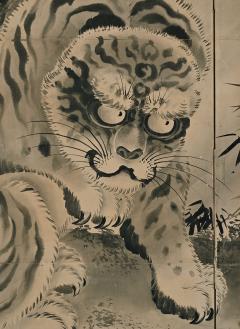

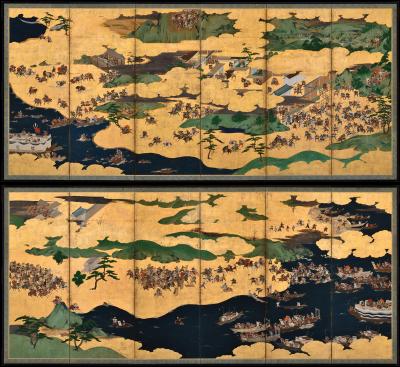

In this grand pair of Japanese Ryuko-zu screens the tiger crouches low to the ground, a sign that the yin earth is the tiger’s territory. Bamboo bends in the force of the wind, said to be created by the tiger’s mighty roar. The tiger’s strength is a quiet power, held in its coiled posture. The dragon, on the other hand, is full of active energy. It emerges out of the yang heavens. Its energy causes rain clouds to swirl and whips the water below into wild waves. The tiger and dragon are ancient symbols of yin and yang, forces that combine to make up the universe.

Japan’s early artistic treatment of tigers is usually highly stylized and this example by Tani Bunchu is no exception. With no indigenous specimens to study, artists of the pre-modern period constructed their notions of the tiger from skins imported into the country. This has resulted in a rather cat-like depiction of this noble creature, capturing the essence of the animal rather than striving for realism. The Japanese dragon, like its Chinese ancestor, is an ancient mythical creature that is very different from its malevolent, treasure-hoarding Western equivalent. The Asian dragon’s origin predates written history, but had achieved its present form of a long, scaled serpentine body, small horns, long whiskers, bushy brows and clawed feet by 9th century Tang ink painting. By this time it was part of Buddhist mythology as a protector of the Buddha and Buddhist law. These traditions were adopted by the Japanese and the character for dragon is much used in temple names. In painting for the Japanese Zen sects, especially, depictions of dragons and tigers were frequently paired and appeared often on the walls and screens of monastic dwelling chambers. The motifs spread from Zen circles into the secular world and especially appealed to the military classes, tigers serving also as symbols of strength and virility.

Tani Bunchu (1823-1876) was a painter of the Tani Buncho school. He learned painting techniques from his father, Tani Bunji (1812-1850), and was an active painter in Edo and Tokyo from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period. Tani Bunji succeeded his father Tani Buncho (1763-1840) as head of the family. Bunji passed away at the young age of 38, and there are only a few paintings left by him. Tani Buncho was a highly eclectic and influential painter working in Edo in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, who mastered a wide variety of historical painting styles from China and Japan. -

More Information

Documentation: Documented elsewhere (similar item) Period: 19th Century Condition: Good. Styles / Movements: Asian Art Incollect Reference #: 755715 -

Dimensions

W. 144.09 in; H. 70.47 in; W. 366 cm; H. 179 cm;

Message from Seller:

Kristan Hauge Japanese Art, based in Kyoto's museum district since 1999, specializes in important Japanese screens and paintings for collectors, decorators, and museums worldwide. Contact us at khauge@mx.bw.dream.jp or +81 75-751-5070 for exceptional access to Japanese art and history.