-

FINE ART

-

FURNITURE & LIGHTING

-

NEW + CUSTOM

-

DECORATIVE ARTS

- JEWELRY

-

INTERIORS

- FEATURED PROJECTS

- East Shore, Seattle, Washington by Kylee Shintaffer Design

- Apartment in Claudio Coello, Madrid by L.A. Studio Interiorismo

- The Apthorp by 2Michaels

- Houston Mid-Century by Jamie Bush + Co.

- Sag Harbor by David Scott

- Park Avenue Aerie by William McIntosh Design

- Sculptural Modern by Kendell Wilkinson Design

- Noho Loft by Frampton Co

- Greenwich, CT by Mark Cunningham Inc

- West End Avenue by Mendelson Group

- VIEW ALL INTERIORS

- INTERIOR DESIGN BOOKS YOU NEED TO KNOW

- Distinctly American: Houses and Interiors by Hendricks Churchill and A Mood, A Thought, A Feeling: Interiors by Young Huh

- Robert Stilin: New Work, The Refined Home: Sheldon Harte and Inside Palm Springs

- Torrey: Private Spaces: Great American Design and Marshall Watson’s Defining Elegance

- Ashe Leandro: Architecture + Interiors, David Kleinberg: Interiors, and The Living Room from The Design Leadership Network

- Cullman & Kravis: Interiors, Nicole Hollis: Artistry of Home, and Michael S. Smith, Classic by Design

- New books by Alyssa Kapito, Rees Roberts + Partners, Gil Schafer, and Bunny Williams: Life in the Garden

- Peter Pennoyer Architects: City | Country and Jed Johnson: Opulent Restraint

- VIEW ALL INTERIOR DESIGN BOOKS

-

MAGAZINE

- FEATURED ARTICLES

- Northern Lights: Lighting the Scandinavian Way

- Milo Baughman: The Father of California Modern

- A Chandelier of Rare Provenance

- The Evergreen Allure of Gustavian Style

- Every Picture Tells a Story: Fine Art Photography

- Vive La France: Mid-Century French Design

- The Timeless Elegance of Barovier & Toso

- Paavo Tynell: The Art of Radical Simplicity

- The Magic of Mid-Century American Design

- Max Ingrand: The Power of Light and Control

- The Maverick Genius of Philip & Kelvin LaVerne

- 10 Pioneers of Modern Scandinavian Design

- The Untamed Genius of Paul Evans

- Pablo Picasso’s Enduring Legacy

- Karl Springer: Maximalist Minimalism

- All Articles

Offered by:

Arader Galleries

1016 Madison Avenue

New York City, NY 10075 , United States

Call Seller

215.735.8811

Showrooms

The Philadelphia Water Works

Price Upon Request

-

Tear Sheet Print

- BoardAdd to Board

-

-

Description

EXHIBITED: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania (n.d.); Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Fairmount Waterworks 1988, p. 29 illus. in color; p. 44 checklist

EX COLL.: [Harry Stone, New York]; [Hirschl and Adler Galleries, New York, by 1984]; to corporate collection, until the present

Inscribed (on the back, twice),Fairmont

Nicolino Calyo's career reflects a restless spirit of enterprise and adventure. Descended in the line of the Viscontes di Calyo of Calabria, the artist was the son of a Neapolitan army officer. (See the brief biographical sketch by Kathleen Foster, prefacing catalogue entry no. 257 in Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, exhib. cat., [1976], pp. 299-301.) Calyo received formal training in art at the Naples Academy. His career took shape amidst the backdrop of the political turbulence of early nineteenth century Italy, Spain, and France. He fled Naples after choosing the losing side of struggles of 1820-21, and, by 1829 was part of an Italian exile community in Malta. This was the keynote of a peripatetic life that saw the artist travel through Europe, to America, to Europe again, and back to America.

Paradoxically, Calyo's stock-in-trade was close observation of people and places, meticulously rendered in the precise topographical tradition of his fellow countrymen, Antonio Canale (called Canaletto) and Francesco Guardi. In search of artistic opportunity and in pursuit of a living, Calyo left Malta, and, by 1834, was on the opposite side of the great Atlantic Ocean, in Baltimore, Maryland. He advertised his skills in the April 16, 1835, edition of the Baltimore American, offering "remarkable views executed from drawings taken on the spot by himself, . . . in which no pains or any resource of his art has been neglected, to render them accurate in every particular" (as quoted in The Art Gallery and The Gallery of the School of Architecture, University of Maryland, College Park, 350 Years of Art & Architecture in Maryland [1984], p. 35). Favoring gouache on paper as his medium, Calyo rendered faithful visual images of familiar locales executed with a degree of skill and polish that was second nature for European academically-trained artists. Indeed, it was the search for this graceful fluency that made American artists eager to travel to Europe and that led American patrons to seek out the works of ambitious newcomers.

Between 1819 and 1822 the city of Philadelphia dammed the Schuylkill River to build the Fairmount Water Works, intended to insure a clean water supply to the growing town. In 1844, the municipality began to acquire the estates along the river bank in order to guarantee the purity of its water supply. The park grew by accrual and, in 1867, was officially established by the Pennsylvania State Legislature. Celebrated for its charming gardens, dams, reservoirs, turning waterwheels, and classically inspired buildings, the Fairmount Waterworks was a favorite spot among Philadelphians for strolling and admiring the scenery along the river. The facility, including the buildings, the machinery, the distribution system, and the surrounding gardens, was largely designed by the engineer Frederick C. Graff (1774-1847) and constructed over a period of about forty years, beginning in 1812.

Since he had served as the assistant to architect and engineer Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), it is not surprising that Graff's designs exhibit the direct influence of his mentor's Neo-Classical style. The machinery of the waterworks was housed in structures based on Greek prototypes that were considered attractive and harmonious with their surroundings.

Calyo's view of the Waterworks is from approximately the same vantage point as that used by Thomas Birch in his famous painting from 1821, The Fairmount Waterworks (The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, bequest of the Charles Graff Estate; see Jane Mork Gibson, The Fairmount Waterworks, in Bulletin: Philadelphia Museum of Art 84, no. 360, 361 [Summer 1988], p. 25 illus. in color). Like Birch before him, Calyo chose the prospect afforded by the western approach to the Upper Ferry Bridge, which crossed the Schuylkill a few hundred feet downstream of the reservoirs, the falls, and the engine (pump) house. The panorama encompasses, from west to east: the lock keeper's house and the canal of the Schuylkill Navigation Company; the low dam across the river; the white gazebo, erected in 1835 on the head pier as part of the general beautification of the Waterworks district; and the Neo-Classical complex of engine house, mill house, and outbuildings designed by Frederick Graff.

Given Nicolino Calyo's obvious affinity for urbane views of American cities (see, for instance, his series of views of New York City), it is not at all surprising that he would have been drawn to this perfectly choreographed setting on the banks of the Schuylkill-a self-conscious bit of historical artifact intended to rival the best that Europe could offer. Calyo, wielding his palette and brush, offers the fine art equivalent to the descriptions of Trollope and Dickens, rendering this picturesque combination of industry, nature, and civilization for the visual delight of the viewer. -

More Information

Documentation: Period: 19th Century Creation Date: 1835-36 Styles / Movements: Other Incollect Reference #: 97790 -

Dimensions

W. 59.5 in; H. 44.25 in; W. 151.13 cm; H. 112.4 cm;

Message from Seller:

Founded in 1971, Arader Galleries is the leading dealer of rare maps, prints, books, and watercolors from the 16th to 19th centuries. Visit us at 1016 Madison Avenue, NYC, or contact us at 215.735.8811 | loricohen@aradergalleries.com |

Sign In To View Price

close

You must Sign In to your account to view the price. If you don’t have an account, please Create an Account below.

More Listings from Arader Galleries View all 1351 listings

No Listings to show.

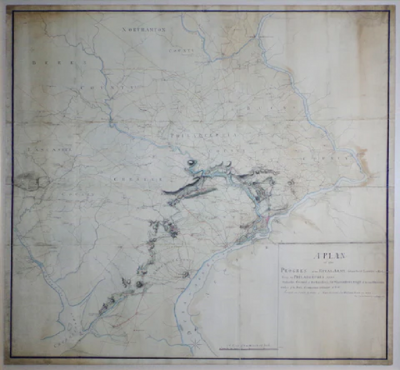

- A PLAN OF THE PROGRESS OF THE ROYAL ARMY FROM THEIR LANDING

- DELAWARE VALLEY DRESSING TABLE (INV. 0331)

- PHILADELPHIA WALNUT CHEST ON FRAME

- ENGLISH NEOCLASSICAL SIDE CHAIR (INV. 0026)

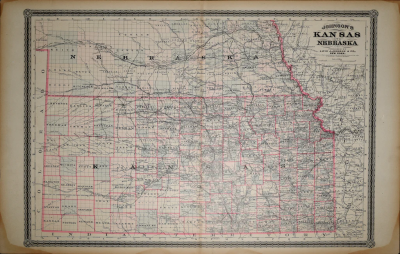

- ALVIN JOHNSON & CO., JOHNSON'S KANSAS AND NEBRASKA

- NORTHERN DELAWARE OR SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA HIGH CHEST OF DRAWERS

- DELAWARE VALLEY, 1760-90, DROP-LEAF OR DINING TABLE (INV. 0355)

- QUEEN ANNE SIDE CHAIR (INV. 0019)

- PHILADELPHIA DRESSING TABLE (INV. 0327)

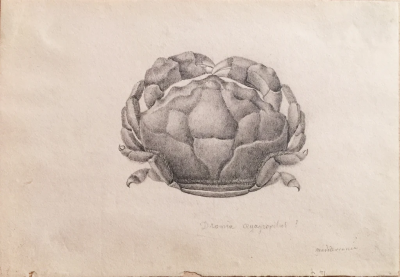

- DRONIA OEGAGROPILUS. MEDITERRANAE

- NEW YORK MAHOGANY SIDE CHAIR (INV. 0322)

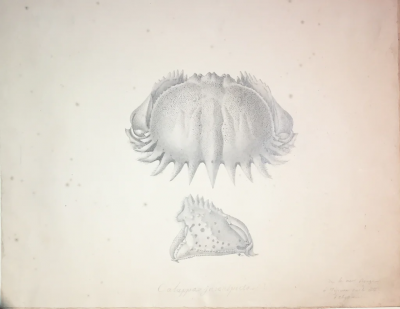

- CALUPPA INCONSPECTRA...

- FEDERAL SADDLE-SEAT SIDE CHAIR (INV. 0024)

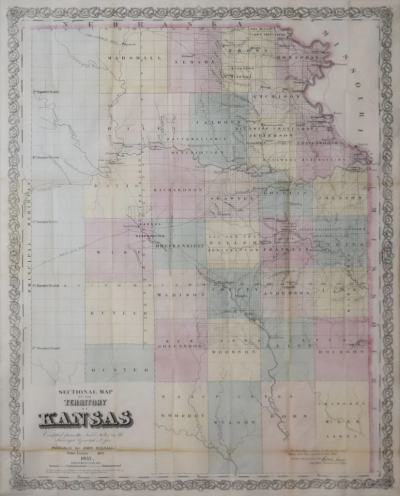

- JOHN HALSALL, SECTIONAL MAP OF THE TERRITORY OF KANSAS...