From the Cradle to the Grave: Privacy and Comfort in New England Bedrooms, 1675–1875

What goes on behind the closed doors of the bedroom raises questions of privacy, comfort, intimacy, and fashion that can be examined through objects as varied as bedsteads and coverlets, nightclothes and cradles, tin tubs and mahogany high chests.

Depicting Dr. Glysson (1750–1793) examining a female patient, Chandler’s painting underscores the use of fully enclosing bed curtains to provide privacy. We see the simple wool harrateen or cheyney curtains most commonly used in Massachusetts during the years 1750–1770, but not the usual shaped and trimmed valances considered an essential part of a set of bed hangings or “furniture.” Throughout the eighteenth century, bed hangings were perceived as useful in protecting sleepers from cold draughts, noxious vapors, and foul night air, but by 1804, some feared that bed hangings were unhealthy, not only trapping dust and vermin, but also preventing the circulation of fresh air, which began to be valued about that time. In spite of those cautions, people continued to use bed hangings as vehicles of fashion and expressions of personal prosperity. Valance designs became more elaborate in the nineteenth century, with white dimity, printed cottons, and silks used instead of woolen fabrics, and with more lavish use of ornamental tapes and fringes.

The exhibition Behind Closed Doors: Asleep in New England, on view at the Concord Museum in Concord, Massachusetts, explores furnishings and activities related to bedrooms and sleep. Objects, prints, and paintings dating from 1675 to 1875 illustrate sleeping, intimacy, childcare, illness, bathing, dressing, birth, and dying. Key themes include the comforts associated with soft feathers, clean linen, and warm blankets; the privacy of a curtained bed; the convenience of a chamberpot; and the effectiveness of a little water and a linen towel in keeping clean. The discomforts of the period are not ignored: sleeping on a thin mattress on the floor, sharing a bed with strangers in a tavern, the presence of bedbugs, the prickly effects of feather spines, curled horsehair, or straw protruding through bedding, and touching bare toes to a cold floor on a winter morning.

In wealthy families, the bedroom or chamber was a separate room in which people slept, entertained guests, and displayed their prosperity with fashionable furniture and many yards of imported textiles, stylishly shaped valances, and costly trimmings used for the bed hangings. A fully hung bed would be fitted with valances and fully enclosing curtains, straw and feather mattresses, bolster and pillows, sheets, blankets, and counterpane. Such a bed was almost always the most expensive item inventoried in any household and, as a result, although styles changed from time to time, many sets of bed hangings remained unchanged for decades. Few people, however, had more than one such bed, and many, if not most, households had only low post bedsteads, fitted with mattresses filled with straw or corn husks. Some beds lay directly on the floor itself. The exhibition displays a family bedstead and trundle bed along with a variety of valance shapes. Hands-on displays of mattresses stuffed with cornhusks and feathers are contrasted with today’s memory-foam mattress material. A video illustrates a high post bedstead with a complete set of hangings.

This embroidered register records the family of Amos and Anna Melvin of Concord. Their first child, Amos Jr. was born nine months to the day after their marriage on January 15, 1782. Anna gave birth to seven sons and three daughters in the twenty years between 1782 and 1802. Not all brides in eighteenth-century Concord were as chaste as Anna may have been; more than one third of first children born in the town between 1756 and 1776 were conceived out of wedlock. In nearby Lexington, the number of “early babies” at this period was similar. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century New England, many women bore a new child every two years. Infant and youth mortality claimed a far greater share than today, to be sure, but many mothers lived to know a dozen children and a score of grandchildren.

Throughout history, bedsteads have been made in different sizes, but this size is fairly common. Made about 1830, it is quite close to the 54 by 75 inch dimensions of the modern double, or standard, mattress. It may appear smaller or shorter than its actual measurements because the sloping contour of the feather-filled mattress is unlike the familiar sharp edges of a modern mattress. Whether out of necessity or preference, it was customary to share beds, even with strangers in hostels. Mothers would take nursing infants into bed with them, and when a new baby arrived, the toddler would move to an adjacent trundle bed, perhaps joining a sibling a few years older. Proximity made caring for a sick child or soothing a frightened dreamer much easier. During the daytime, trundle beds were pushed underneath adult beds, out of sight until needed again in the evening.

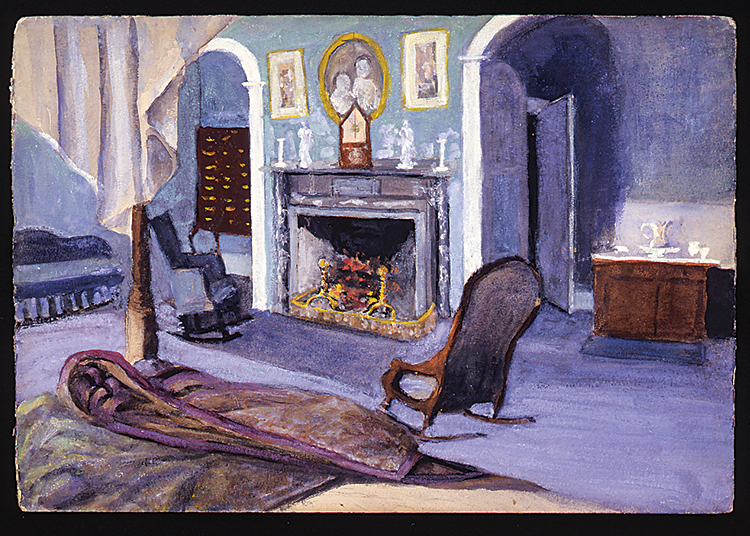

This painting by his grandson records Ralph Waldo Emerson’s bedchamber essentially as it had been since 1873. Much of the furniture and many decorative accessories had been rescued from the fire that substantially damaged the roof and second floor of the Emerson house in July of 1872. The eighteenth-century four-post bedstead has white dimity hangings, perhaps remade from those that Ellen Emerson recorded in the sketch (below) of her mother, Lidian, in bed with the cats. On the bed lies Emerson’s blue woolen dressing gown.

- Lidian Emerson in bed with cats Topaz and Milcah, about 1864. Pencil sketch by Ellen Tucker Emerson, from Ellen Tucker Emerson, A.MS.s, v.p., n.d.; Courtesy, Houghton Library, Harvard University (BMS Am1280.235 [358]). Published in The Life of Lidian Jackson Emerson by Ellen Tucker Emerson (Michigan State University Press, 1992).

In middle life, Lidian Emerson customarily had her breakfast in bed and for a time she enjoyed watching the little cats jump on and off the bed while jealously paying close attention to each bite she ate. Her daughter Ellen worried that this game tired her mother and interfered with her proper nourishment. When Lidian Jackson inherited this four-post bedstead from her Aunt Lucy, it had two sets of curtains—one of tan chintz printed with bright flowers, the other, white cotton dimity with matching window curtains was considered the “best.” The dimity curtains were hung in anticipation of the birth of Lidian’s first child, but when her husband, Ralph Waldo Emerson, pronounced that they had “too much parade,” she took them down in deference to his opinion. Nevertheless, she had them hung again in 1839 in preparation for her daughter Ellen’s birth and used them during the subsequent “sitting up week.” Perhaps he didn’t notice.

- Cradle, maker unknown, Barnstable or Yarmouth, Mass., 1665–1685. Red oak, white pine. H. 32¾, W. 16⅝, D. 33½ inches. Courtesy, Historic New England; Gift of Dorothy Armour, Elizabeth T. Acampora, L. Hope Carter, Guido R. Perera, Henry C. Thacher, Louis B. Thacher Jr., and Thomas C. Thacher (1958.100). Photography by Peter Harholdt.

It may have been to celebrate the arrival of a new male heir that this elaborate and sophisticated cradle was commissioned with its numerous panels and turnings. Over the centuries, legends wound around this cradle and made it an icon of heritage and tradition for the Thacher family. Furniture historians now agree that the cradle was made about 1675 or 1680, but like many New England families eager to underscore the early arrival of their first English ancestor, the Thachers long insisted that its first occupant was John Thacher, who was born in 1639 in Yarmouth on Cape Cod. Similarly, the cradle associated with the Fuller family in Plymouth was first illustrated in a Plymouth guidebook of 1845 and exhibited as a Pilgrim icon in the nation’s centennial exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, though it too appears to have been made no earlier than 1680.

This coffin with its traditional shape and handsome moldings is said to have been used for decades in Hancock, New Hampshire, as the “town coffin” in which paupers were carried to the cemetery. When a person died in New England, it was customary for the corpse to be wrapped in a sheet or dressed in an enveloping garment called a shroud. As soon as the coffin was ready, the body was placed inside and then displayed in the open coffin on a table in the parlor, or on the bed in the bedchamber before the funeral service, which was usually held at home. Before being carried in procession to the place of burial, the lid of the coffin was closed. Since this coffin bears no evidence of having a lid nailed down, it may have been only loosely covered as it was moved away. After this coffin ceased to be used as a common coffin in Hancock, it was stored in a barn and used for feeding chickens, which explains its scratched interior.

Bedrooms often served as the setting for the universal passage from cradle to grave. Most young mothers delivered their babies in a bedroom at home, with their own mother, sisters, or some neighbor women, and usually a midwife or doctor in attendance. New mothers were encouraged to rest after delivery, sequestered from the bustle of the household, and often confined to bed. The dangers of infection were not yet known, but this customary isolation of mother and newborn child provided some protection, as well as an opportunity to rest and recover from the rigors of childbirth. The length of the lying-in period varied from several hours to as much as a month, depending on health, available help, community social standards, and personal preference. In some places, the period of confinement was followed by a formal “sitting-up week,” where a new mother would show her newborn to friends and family in her best bedchamber, while entertaining them with tea and cakes. Illustrating the beginning and end of life in the exhibition are the magnificent seventeenth-century Thacher cradle, a family bed and trundle, an imposingly large adult cradle, and the common coffin used for paupers in a New Hampshire town.

This article includes a selection of objects on view in the exhibition. In addition to the gallery displays, five period rooms are presented as stage sets for daily life, including a parlor prepared for the entertainment of guests following a funeral. Behind Closed Doors, Asleep in New England, is on view at the Concord Museum, Concord, Massachusetts, until March 22, 2015. For information call 978.369.9763 or visit www.concordmuseum.org.

Jane Nylander, and her husband, Richard Nylander, served as consulting curators to Behind Closed Doors: Asleep in New England. Retired from long careers in museum administration and curatorial work, they continue to be actively involved in local and national museums and cultural organizations.

This article was originally published in the Anniversary 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.