Fans, Tassels, and Bellflowers: Idiosyncratic Inlaid Furniture of Northeastern Tennessee Part II

In the 15th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art Magazine, I discussed the idiosyncratic inlay used by cabinetmakers in Washington County, Tennessee.1 This present article continues the discussion of the furniture of Northeastern Tennessee by focusing on Greene County.

Greene County was formed out of Washington County in 1783, when Tennessee was still a territory. The two county seats—Jonesboro and Greeneville—are separated by only twenty five miles. Like Jonesboro in Washington County, Greeneville was an early town with the first settlers pitching tents there by 1772. In 1971, when the first scholarly work on Tennessee furniture was published, Ellen Beasley noted “the most distinguishable Tennessee furniture located to date” was from Greene County.2 This was due in large part to a devoted group of collectors in the mid-twentieth century who amassed significant collections of locally made wares that allow confident attribution of furniture to the area.3

There were a scant number of recorded cabinetmakers in Greene County before 1820, but the local cabinetmaking tradition grew, and by 1850 there were at least twenty. Two cabinetmakers are found in the 1820 U.S. Census of Manufacturers, and they offered conflicting views of the cabinet trade in the county. John Matthews, who employed one man in addition to himself, noted in the 1820 Manufacturer’s Census, “Shop not well conducted but the demand is great–and Sales brisk for all made.” William McClure, on the other hand, whose shop employed three men, commented there was “no great demand for wares.” 4 Most likely, was one of these two men were responsible for the group of furniture from Greene County discussed here.5

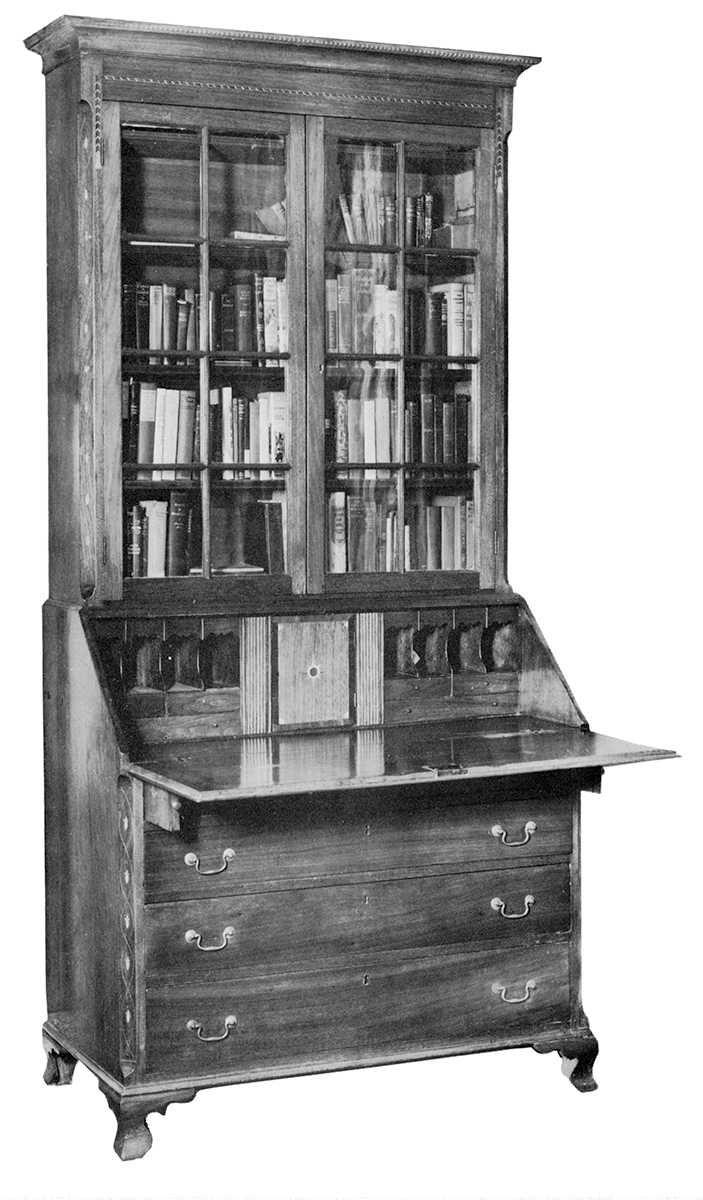

Aside from rope and tassel inlay found on the furniture from both counties, upturned bellflowers and variegated stars are persistent motifs in the decorative vocabulary of the cabinetmakers from Greene County. The desk and bookcase illustrated in Figure 1 is known primarily through a photograph in The Magazine Antiques in 1971. It is one of the earliest examples of Greeneville furniture and incorporates both upturned bellflowers and rope and tassel inlay motifs. This upturned bellflower has a precedent in the furniture of Winchester, Virginia.6 While the rope and tassel motif is seen on numerous pieces from northeastern Tennessee, it is possible to distinguish them from one another by careful examination of the composition of the rope, the design of the tassel, the way the rope is handled at the corner (either looped or at a 90 degree angle), and the placement of the tassel on the stile. Unlike the rope and tassels from the Washington County group, this rope has a straight angle at the corner and the tassel is very narrow and only slightly bell-shaped.

The desk in Figure 2 has the same interior layout as the desk and bookcase—drawer arrangement, shape of valences and dividers, and prospect door and document drawers. The deep valences on both pieces conceal drawers. This desk has less inlay but displays bellflowers of the same shape that are also upturned (Fig. 2a). The uppermost bellflower on the canted corner of this desk has a curious short trailing stem that is reminiscent of the vine-like tail on the single bellflowers seen on the pieces with colored inlay from Washington County.7 A china cupboard from the same shop (Figs. 3, 3a, 3b) repeats the rope and tassel inlay of figure 1, and adds variegated stars and carefully delineated corner fans with very narrow flutes to the vocabulary of Greene County inlay designs. The flowerpots in the pediment are the only known instance of this inlay motif. A corner cupboard (Fig. 4), also known from its inclusion in the 1971 article, repeats the identical rope and tassel seen on figure 1, the corner fans and similar variegated stars from figure 3, and has large quartered ovals on the lower doors.8 These ovals are similar to the ones seen in a much smaller format on the pieces from Washington County. A tall chest from the same shop (Fig. 5) has a sequence of upturned bellflowers with a trailing stem like the uppermost bellflower in the canted corners of the desk illustrated in figure 2.

These five pieces form the core of inlaid work from this shop. A desk (Figs. 6, 6a) also appears to be from this same Greeneville shop, but shows some slight variations. It has the same basic layout of the interior, the same canted corners, and the same spurred ogee feet; but it features a molded surround to the prospect door and document drawers, and the valences on the upper drawers, while deep, are a different pattern. This desk lacks inlay on its exterior but features exuberant inlay on the interior. This decoration illustrates the relationship of inlay details between Greene and Washington Counties. Although not as well executed, the eagle and banner call to mind the fallboard of the Winterthur desk illustrated in the previous article. Presumably the lozenges in the banner are meant to be stars, and as on the Winterthur desk, there are seventeen, which may represent the number of states at the time the desk was made. The interior drawers feature the quartered ovals found in the canted corners of a chest from Washington County and as seen in large format on the lower doors of figure 4. The fans in the corners of the interior doors are delineated in the same manner as the fans on figures 3 and 4.9

A tall clock (Fig. 7) with a history of descent in the Galbraith family of Greeneville is also closely related to this core group. The bellflowers, while still upturned and with a curling stem, are shaped differently than those on figures 1, 2, and 5; the single bellflowers and stems are contained within looped stringing on the canted corners in a like manner to those on the desk and bookcase in figure 1. The quarter fans are not identical to, but are delineated like, the quarter fans in figures 3 and 4. The wave inlay above the case door is related to the running astragal inlay found on the prospect door of the Washington County desk at Winterthur and the sideboard illustrated in the previous article.

Traditionally attributed to East Tennessee and more specifically to Greene County are a group of cupboards that feature rope and tassel inlay in the frieze, gamecocks facing off against each other on the upper cupboard doors, and a large diamond in the lower doors.10 The discovery of figure 8 by Marianne P. Ramsey has resulted in a tentative attribution of all the cupboards with inlaid gamecocks to Kentucky, not East Tennessee. Figure 8 has remained in the same family since it was made for Alexander Harlin (1813–1866) for use in his log house located in Gamaliel, Monroe County, Kentucky. The early attribution to Greene County seems to have been based on the presence of the rope and tassel inlay, which was known early and well-documented in Greene County. A closer examination of the provenance of these cupboards reveals, however, that all the gamecock-inlaid cupboards with any history were associated with Kentucky. Indeed, while the right angles of the rope in the frieze relates to those found on Greene County furniture, the shape and placement of the tassel, the use of added color on the inlay, and the overall architecture of piece bear more relationship to the MESDA corner cupboard from Washington County pictured in my previous article as figure 5. This cupboard illustrates the cross-pollination of design sources between Greene and Washington Counties by a cabinetmaker who must surely have worked in East Tennessee before relocating to Kentucky.11

It is difficult to leave the topic of rope and tassel inlay without mention of the cupboard illustrated in Figure 9. This piece was bought in the 1930s from the Dykes estate in Hawkins County, from whence it has traditionally been attributed; Hawkins borders Greene County to the north. This cupboard is a tour de force of rope and tassel inlay, with the design present not just in the frieze and stiles of the case but also on the stile and upper rails of the cabinet doors. The same rope is used as an inlaid surround to the lower doors. Patriotic spread-wing eagles are not the only birds found on furniture from Upper East Tennessee. This bird is difficult to identify but may be an eagle or a hawk.12

While furniture made in Washington County can be distinguished from that of Greene County, design influences crossed very permeable county and state lines, and idiosyncratic inlay motifs that seem distinct to one shop in one county often appear in modified form in the work of shops in another county. Further research may lend enlightenment as to the identity and location of the cabinetmakers who produced this distinctive inlaid furniture.

Anne S. McPherson is an independent scholar, furniture historian, consultant, and private dealer based in Nashville, Tennessee.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

Antiques & Fine Art, 15th Anniversary/Spring 14, no. 1 (2015): 104–111.

2. Ellen Beasley, “Tennessee Furniture and Its Makers.” The Magazine Antiques 100,

no. 3 (September 1971): 429.

3. This group of collectors included Richard Doughty, Judd Brumley, Mr. And Mrs. Thomas Overall, Mr. And Mrs. O.C. Armitage, and Mrs. T.D. Brabson.

4. See Ellen Beasley, “Tennessee Cabinetmakers and Chairmakers Through 1840.” The Magazine Antiques 100, no. 4 (October 1971): 612–621; and Derita Coleman Williams and Nathan Harsh, The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture and Its Makers, Through 1850 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society and Tennessee State Museum Foundation, 1988), 271–323. The MESDA craftsman database lists two other names of possible cabinetmakers in Greene County before 1820. The 1812 inventory of the estate of Anthony Kelly lists tools which would be appropriate for a cabinetmaker. The database also references a Benjamin Armstrong who died in 1811; it is possible that this is the same individual as Benjamin D. Armstrong recorded as a cabinetmaker in court records in Cocke and Roane Counties in 1808 and 1809. In any event, neither Kelly nor Armstrong are likely candidates for having produced this large group of work, some of which post-dates their time frames.

5. The 1820 U.S. census for Greene County (and most of East Tennessee) does not survive. John Matthews is listed in both the 1830, 1840, and 1850 U.S. Census; in both 1830 and 1840, Matthews listed in his household men of an appropriate age to be apprentices and/or journeymen. In the 1850 census he lists Valentine Harris, age 19, as a cabinetmaker living in his household. William McClure is listed in the 1808 will of his father, a resident of Washington County. McClure married in Greene County in 1813 and is listed in the extant tax records for that county in 1810, 1812, and 1813. In 1825, James McClaughen advertised that he was operating as a cabinetmaker in the shop previously occupied by William McClure. McClure seems to have left the area by that time.

6. This upturned bellflower is found on a cellaret in the collection of Winterthur and a sofa

in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg, as well as on numerous pieces of furniture, including a tall case clock. See Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1820: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Williamsburg, 1997), 147–152, no. 40 and figs. 40.1–8.

7. There are also a couple of relatively plain desk and bookcases from this same shop that are slightly later in date and with French feet and shaped skirts. One desk and bookcase is illustrated in Anne S. McPherson, “Adaptation and Reinterpretation: The Transfer of Furniture Styles from Philadelphia to Winchester to Tennessee.” American Furniture 1997 (Chipstone Foundation), as figure 34. Both are illustrated in Williams and Harsh, The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture, figs. 59 and 71.

8. A walnut corner cupboard from this same shop was sold by Brunk Auctions as lot 101 on May 12, 2012. It has the same arched glazed doors, the same rope and tassel and variegated stars, and the same cornice and mid-moldings. The arched glazed doors, the medial molding, and the shape of the cornice on these inlaid cupboards allow for the attribution of at least two plain corner cupboards to the same shop.

9. This desk was sold by Guy Bowers, a dealer in Greeneville, in the mid-twentieth century.

10. See Williams and Harsh, figs. 216, 217, and 218. The cupboards in figs. 217and 218 are recorded at MESDA as S-2648 and S-4382, respectively. Another of these cupboards is illustrated in Namuni Hale Young, Art and Furniture of East Tennessee (East Tennessee Historical Society, 1997), 30, fig. 54.

11. These cupboards with inlaid gamecocks are the subject of further research by the author.

12. The same bird is also found on the fallboard of a desk that was collected in Greeneville in the 1930s. The desk bears the inlaid initials “WDR” and the date 1823 in the lower corners of the fallboard. See Williams and Harsh, fig 67.