Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America

In 1824, Elizabeth Negus wrote to her brother-in-law, artist Nathan Negus, acknowledging receipt of a posthumous portrait of her deceased husband: “Most sincerely do I return to you my thanks for the emotion you took in painting Joseph[s] portrait . . . It is a pleasure & a pain for me to look at it.” 1 In those few words, she captured the complexity of emotions that informed the decision to commission a portrait of a loved one who had died. Such portraits served to reinforce a sense of grief and hence a visceral and ongoing acknowledgement of loss, but they also provided comfort each time they came into view. The posthumous portrait was in effect a shadow, a memory preserved in colored pigments on canvas. The history of portraiture itself is based on a shadow; the outline of a departing lover’s profile, traced on a wall by a maid of Corinth: absence pictured as presence.

The painter Horace Bundy was but one of many artists who capitalized on the fear that a family member might die before he or she was portrayed when he advertised in the West Troy Advocate (New York) in 1851: My paintings are fine, the likenesses true;/The pencil was dipt in nature’s own hue;/All glowing and lifelike, you may there behold,/Each delicate feature of both young and old./Then call on the painter, don’t let it be said/“I don’t feel quite able,” till that loved one is dead.2

Such regrets might especially torment the parent whose child was painted only after death and whose passage on earth was too brief to leave more than a faint imprint. Posthumous portraits were proof of life, a visual record and physical presence that, when viewed alongside other family portraits, contributed to the illusion that the family constellation was whole.

The earliest memorial portraits in America were rather more straightforward in their objectives, and functioned as commemorative mortuary or deathbed renderings that made no attempt to spark new life into the memories of those who had passed. An epitaph penned by diarist Samuel Sewall in 1706, suggests the tradition of painting such deathbed portraits was already well established by the turn of the eighteenth century: This morning Tom Child, the Painter, died: Tom Child had often painted Death,/But never to the Life, before:/Doing it now, he’s out of Breath;/He paints it once, and paints no more.3

Portraits that captured a living rather than a postmortem likeness occurred by the mid-eighteenth century as carvings on gravestones. The shift toward realistic depictions of the deceased and away from allegorical and emblematic representations reflected larger changes in the social structure of dying. Puritan beliefs and the intimate acquaintance with death during the colonial period had nurtured practical and unsentimental attitudes toward the corpse. The body was merely a vessel that was emptied of meaning once life had fled; beyond a respectful burial no special treatment was necessitated. As the nineteenth century progressed, an increasing emphasis on the individual influenced the regard with which the corpse was treated, as a hallowed entity retaining its own unique identity. Children especially were reverenced as innocents whose deaths were testaments of faith, and who would be received by Christ in the kingdom of heaven. As the concept of the nuclear family continued to deepen in significance, the more difficult it became to accept a break in that circle, even though religious conviction declared the circle would be whole once again. Stones marking the graves of children featured variations of an epitaph that expressed similar sentiments: “Farewell dear parents I am at rest and shall forever be/I could not stay with you on earth but you can come to me.”

In 1772, Rachel Peale requested her husband, the artist Charles Willson Peale, to paint a portrait of their recently deceased infant daughter Margaret Bordley, the fourth of their children to die.4 The original canvas was a stark affair conceived in the format of a mortuary or deathbed portrait. The infant, her face seemingly drained of blood, shows no traces of the ravages of smallpox, the disease to which she had succumbed. The pale figure, dressed all in white, is laid out on draped white linens like a ghostly marble sculpture against an impenetrable dark background. The baby’s mouth is held closed by a chinstrap sewn to her cap, and her arms are bound to her sides with a white silk ribbon. Peale enlarged the composition in 1776, adding a likeness of his wife grieving over the body of their child, and a table behind her laden with bottles of medicine that proved to be futile. By doing so, he transformed a portrait of private pain into a display of public sentiment. The mother’s heightened color and mulberry dress provide a strong contrast to the colorless child, further shifting emphasis from the innocent’s death to the sanctified act of mourning. Rachel, her teary eyes lifted to heaven, becomes both an individual bereaved by the death of her child and a codified figure of grief, evoking art historical precedents and the universality of loss.

In 1776, after visiting Peale’s painting rooms in Annapolis, Maryland, John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, noting: “He showed me one moving Picture. His wife, all bathed in Tears, with a Child about six months old, laid out, upon her Lap. This Picture struck me prodigiously.” 5 Subsequently, Peale moved his painting rooms to Philadelphia, the first skylighted gallery in America. There he advertised in 1782 the display of Mrs. Peale Lamenting the Death of Her Child.6 To heighten the pathos, he placed the painting behind a curtain pinned with a poem:

Draw not the curtain, if a tear

Just tremblng in a parent’s eye.

Can fill your gentle soul with fear

Or arouse your tender heart to sigh.

A child lies dead before your eyes

And seems no more than molded clay.

While the affected mothers cries,

And constant mourns from day to day.

In many family portraits that include both living members and those who have died, the deceased are arranged in a naturalistic manner so as to present them as a critical presence in the family constellation. But how does one depict memory? The members of this family are unidentified, but the impressive size and panoramic presentation leave little doubt as to the loss suffered by these parents. On the far left, the mother wraps one arm protectively around her living daughter. In her other hand she holds a volume of Mrs. Chapone’s Letters, first published in London in 1773, a popular book offering advice and moral guidance that she will pass on to this cherished child. On the far right, the father holds an untitled volume in one hand and rests his other hand on the shoulder of his surviving son. Perhaps in tribute to his deceased brother, the boy holds a vivid red flower with tri-lobe leaves, possibly the crimson clover, a flower that dies once it has bloomed. Three-part leaves or petals are sometimes a reference to the Holy Trinity, an interpretation that is reinforced by the flower’s Latin name, Incarnatum, that means “blood red.” Set behind these figures, and occupying an ambiguous nether plane, are two young and identically dressed children, possibly a brother and sister, who are at once part of the scene and separate from it; lost but not forgotten. Each holds an emblem: a dead bird and a drooping white flower. Many symbols seen in posthumous portraits encode a duality of meaning expressive of opposite states. Birds can represent birth, death, or rebirth. In Connecticut artist John Brewster’s portrait of Francis O. Watts (Fenimore Art Museum) a bird that soars yet remains tethered to a string held by a child represents his soul bound to this earth. The meaning of the bird held upside down in this depiction, however, is unequivocal, as is the withered white flower that speaks of an innocent life lost before its bloom.

Posthumous portraits were not usually memorials in a strict sense. Rather, they were intended to keep the semblance of a loved one present beyond the living memories of immediate family members and friends. Symbols that indicate the deceased status of the subject were often included, but they may be subtle and not intended to detract from the living aspect of the portrait itself. In this composition Theodoric Myers stands before a thicket, his figure outlined by foliage, and he is separated from the distant horizon by a deep lake. The striking sunset reflected on the still surface of the lake accomplishes its purpose of informing the viewer that the life of this child has ended, but it also adds to the beauty and meaning of the representation. In Greek mythology the newly dead are escorted across the river Styx by a ferryman, perhaps betokened here by the rowboat barely visible beyond the growth that suggests the boy has recently crossed the waters. In some versions of the myth, the waters themselves held the power of immortality. In Christianity, the lake may be a reference to baptism water, strengthened by the cryptic basket of fish held in the child’s hand. This is a less accessible symbolic element that may be a reference to Christ as the “fisher of men” who fed five thousand with two fish and five loaves.

Theodoric was born in 1833 and christened in 1834, according to the records of the Dutch Reformed Church in Berne, Albany County, New York. He was probably the son of Reverend Abraham H. Myers, who served in many German and Dutch Reformed Churches in New Jersey and upstate New York. An inscription on the back of the painting indicates that Theodoric was portrayed in 1840 at the age of seven, and it is signed “J. B. Gregory artist.” Gregory has yet to be identified, though an English-born artist, James B. Gregory, is listed in the 1850 Federal census as a painter living in Greene County, New York. Theodoric’s eighteen-month-old sister Henriette Josepha was painted at the same time, perhaps an attempt on the part of her bereft parents to claim a living shadow in the event she too died at a young age.

Most of the portraits in this exhibition are identified as posthumous through family tradition or inscriptions on the canvases. When a painting has survived with no information about the sitter, however, positing whether or not it is posthumous must be based on the details present in the depiction. Often it is a complex of symbols rather than any single motif that indicates the probability a portrait was painted after death. A reassessment of some of the most beloved paintings of children suggests more may be of the posthumous genre than has previously been supposed. This is one of several similar canvases painted by the Boston/Charlestown-based artist Samuel S. Miller. Each features a standing child with little facial affect, a goldfinch, roses, and sometimes even a sunset. Though these elements alone may not offer conclusive evidence that the subject is deceased, this portrait reveals symbols specifically associated with death, mourning, and resurrection that leave little doubt as to its nature.

The young girl holds a basket of flowers over one arm that includes a morning glory, a flower that blooms each morning only to wither as the light fades each evening, suggesting mortality and rebirth. With her other hand she plucks a blossom from a growing rose bush, a well-known symbol of a young life ended too soon. The child tramples a daisy under her left foot, a flower associated with innocence, purity, and new beginnings, and a sad-eyed cat by her right foot pounces on an unopened white rosebud, a torn leaf in its mouth. A stand of flowers, possibly lilies or narcissus, further strengthens the association with death and resurrection. If lilies, they symbolize innocence through their association with the Virgin Mary. If narcissus, their name refers to the Greek myth of the youth so infatuated with his reflection that he died of unrequited love; and to Persephone, abducted by Hades while gathering the flowers and who thereafter reigned as queen of the underworld.

In concert with the other symbols the goldfinch now assumes meaning not as an allusion to the living spirit of the child, but as a reminder of the Passion of Christ. In one popular legend, a goldfinch pulled a splinter from Christ’s crown of thorns during his march to Calvary. As a result, the goldfinch became a symbol prefiguring knowledge of the crucifixion of Christ.7

A careful reading of this portrait reveals it was painted posthumously. The color combination of red, black, and white has a long history with mourning. The red draped curtain, in particular, recalls the color of cloth palls traditionally laid over the coffin in a funeral procession.8 The color holds deep art historical associations with the robes worn by Jesus’ mother, Mary. In this portrait it may subtly allude to the subject’s death in childbirth. Catharine Slade holds a remembrance book or friendship album on her lap, opened to a page with a rendering of a thorny rose in full bloom and unopened buds. In Greek mythology and early Roman culture, the rose had already assumed dimensions as a symbol of death. Over time it also became a privileged Marian symbol, its thorns a testament to the sacrifice to come. Its complex circular formation was also a symbol of God’s universe, a prominent feature in the rose windows of the great Gothic cathedrals, evoked by the rose form of the drapery pull. A grove of cypress trees, symbols of death and resurrection, is glimpsed through the window further affirming the posthumous nature of this portrait.

Catharine died in 1844, and was probably painted soon thereafter by Susan C. Waters, according to a note on the strainer.9 Waters is known to have worked in the area of Kelloggsville, Cayuga County, New York, not far from Sempronius, where the Slades lived. A surviving letter written by Catharine’s sister to her son and daughter-in-law details the circumstances of her death:

Alice I think you chose a pretty name for your little baby. I had a sister Catharine and she married Barton Slade. Barty is his namesake he was a nice man and a kind Husband. They was married about three years. Her first baby did not live but about three hours and then she had another one in due time and she died the third day after it was born of childbed fever. The[y] called it Catharine and it lived until it was sixteen months old and died, the Dr. thot [sic] teething, and it had high fever.10

Catherine Slade died from puerperal fever, one of the most common causes of death for women following childbirth. The infection was introduced by unhygienic medical implements and practices and usually set in around three days after birth. Her daughter died less than two years later from “teething fever.” Because teething coincided with the highest rate of infant mortality, between six months and two years of age, it was widely believed that the developmental stage could prove fatal. As a result a number of dire remedies were applied that in fact often hastened the death of the child.11

Postmortem daguerreotypes did not immediately displace painted posthumous portraits when they first gained currency in around 1841. Initially, the daguerreotypes often served as the copy source for the painting, relieving some of the less pleasant aspects of posthumous portraiture, such as the need for a painter to physically engage with the corpse. In a very real sense daguerreotypes erased social distinctions in the posthumous portrait genre as they became more and more affordable. Through the 1860s, a family might commission both a painted and a photographic portrait after a death, sometimes even years apart. Each medium performed a different function for the bereaved. The painted portrait had the ability to reanimate a lifeless body, thus preserving a living memory, while the daguerreotype captured the body itself in all the solemnity of the passage from this world to the next. And together, they provided a remarkable mechanism for preserving the wholeness of the family. In this instance, William Matthew Prior’s portrait enables mother and child to pose together, a picture of loss that is both acknowledged and denied.

One of the most intriguing motifs seen in nineteenth-century portraits of children is “one shoe off.” Once believed to always indicate a subject was deceased, canvases have since been discovered whose identified sitters are known to have lived long past the date of the portrait. Yet when juxtaposed with other unambiguous symbols included in the lexicon of death and mourning, the tossed shoe may assume Christological dimensions. The genesis of the trope may derive from the venerated fifteenth-century Byzantine icon, Our Lady of Perpetual Help. In this representation, the Infant Jesus sits on his mother’s lap, one sandal dangling off his foot. One interpretation suggests the sandal symbolizes Christ’s divine nature, already loosening his hold on the world, while the sandal that remains on his other foot is suggestive of his dual nature as man and as Son of God. In William Matthew Prior’s rendition, the child holds the sock in one hand and the shoe in the other in a formal gesture. When the motif is included as a symbol of childhood, it is typically shown as the more natural action of kicking one shoe off. Prior has further conflated the concept with a thread that is unspooled. This is a variation of the symbol of a cut thread, referring to Atropos, one of the three Fates who cuts the thread of life for each mortal.

- Little Drummer Girl: Sarah A. Lawrence of 119 Hudson Avenue, photographer unidentified, Green Island, Albany County, New York, ca. 1847. Sixth-plate daguerreotype, hand colored. © Stanley B. Burns, MD & The Burns Archive; www.burnsarchive.com.

Posthumous portraits of children often included favorite toys and other familiar objects. This practice was continued in the transition to the daguerreotype, intensifying both the intimacy and individuality of the portrait and its poignant power to affect the viewer. In studies of gender identification in nineteenth-century self-taught art, the hairstyle and toy drum seen in this daguerreotype are primarily associated with portraits of young boys. The identification that has descended with this spectacular daguerreotype, however, names the child as Sarah A. Lawrence of Albany County, New York, perhaps accounting for the choice of brilliant pink and red coloring for the dress, drum, and ribbons.12 The luscious rosy-tones introduced through hand coloring testify to the expense lavished on this image. Despite the attempt to make the child look as though standing upright, the shadowy depression and resulting wrinkles in the fabric, the incline of the drum leaning into the sheets, and the child’s blank stare still easily identify this as a daguerreotype taken after death.

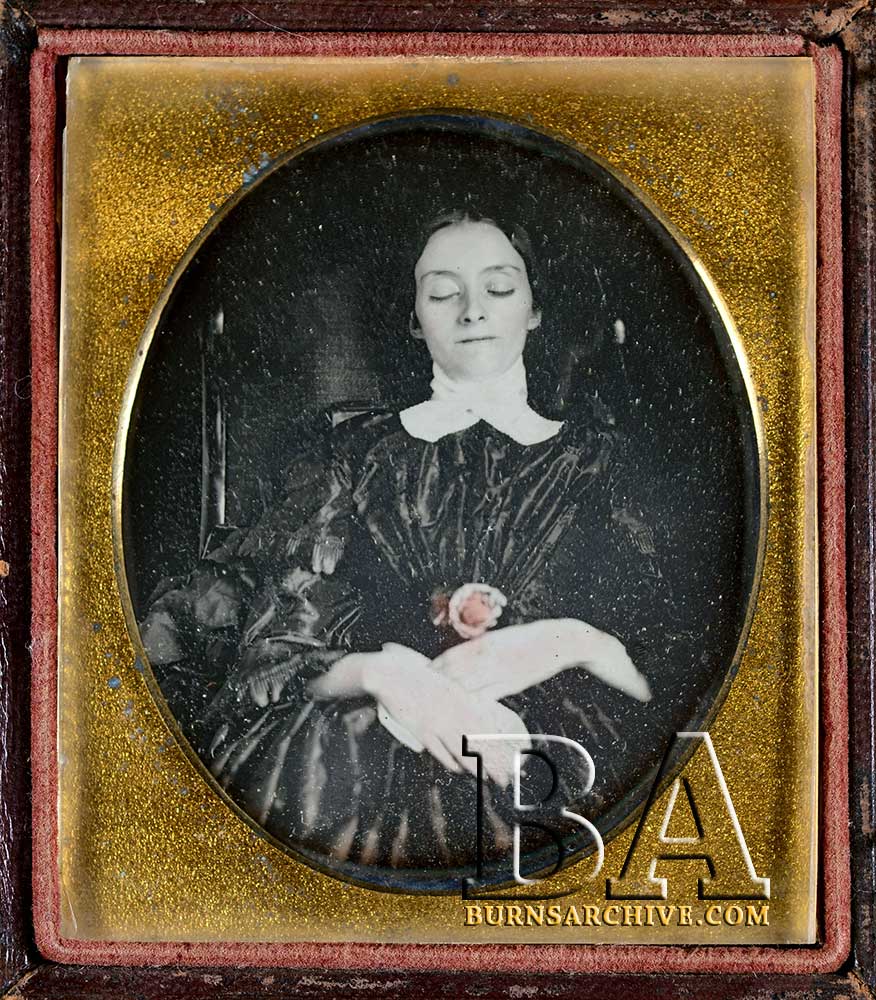

- Young Woman with a Rose, photographer unidentified, United States, ca. 1844. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. © Stanley B. Burns, MD & The Burns Archive; www.burnsarchive.com.

In 1855, photographer N. G. Burgess offered remarks on taking portraits after death that were published in the March 1855 issue of The Photographic and Fine-Art Journal. He observed that, “All likeness taken after death will of course only resemble the inanimate body, nor will there appear in the portrait anything like life itself, except indeed the sleeping infant, on whose face the playful smile of innocence sometimes steals even after death. This may be and is often transferred to the silver plate. However, all the portraits taken in this manner, will be changed from what they would be if taken in life—all will be changed to the somber hue of death.” This unusually beautiful and serene image, with a hand-colored rose held in the young woman’s hands, transcends the “somber hue of death” and suggests instead the sleep of an innocent child.

- Memorial to Nicholas M. S. Catlin, artist unidentified, probably Tioga, New York, ca. 1852

Oil on canvas, 38-3/4 x 28-13/16 inches

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch (1955.11.7)

Inscribed on monument: “In Memory of/Nicholas M.S. Catlin/Son of/ Nathan S. & Phebe C. Catlin/Died/April 19th 1852/Aged 1 yr. 1 mo 15 days.”

The portrait of Nicholas M. S. Catlin functions explicitly as a memorial and includes iconography associated with mourning art in other mediums, such as needlework. A plinth inscribed with the child’s name, date of death, and exact age, replicates the information on his actual gravestone in the Tioga Cemetery, New York, where he is interred. Despite such veristic details, the portrait is somewhat fictive in its conception and may mark the desire of the boy’s father, Nathan S. Catlin, to honor his child with this elevated tribute. In truth, the obelisk form of the grave marker in the depiction is an aspiration; the actual stone is merely an unadorned rectangular marker with none of the elegance of the stone in this portrayal. Nor does the location of the gravestone stand near a weeping willow, with a body of water in the distance. There is some conjecture that this view reflects the prospect of the Finger Lakes seen from the Greek Revival home purportedly built by Nathan S. Catlin.13 Such elements, though, belong to a well-established canon of symbols associated with death, burial, and mourning.

The child is pulling an unopened rose from a triangular tower of blooms that include forget-me-nots and other flowers associated with remembrance and innocence. A cat with a preternatural stare arrests the viewer, prepared to escort the soul of the child to the afterlife. It is not known what caused the death of this young boy. Posthumous portraits typically did not reflect any unsightly effects of disease. The pronounced roll of childish flesh around Nicholas’ neck was most probably simply a reflection of his young age, emphasized if the child was painted from corpse while he lay on a bed or board. But, as a portrait painted after death, it is also a reminder that the artist was not always able to fully disguise a suggestion of a disease such as diphtheria, marked by a pronounced swelling of the throat.

Many of the portrait painters who are well known today accepted commissions to paint posthumous portraits, especially at the beginning of a career; some, including William Matthew Prior (1806–1873) and Joseph Whiting Stock (1815–1855), even made it a regular part of their practice. This may have been due in part to their own specific experiences and empathies. Prior’s belief in spiritualism allowed him to claim the ability to see visions of those who had passed. This gift enabled him to paint portraits from “spirit effect,” including his brother Barker, whom Prior portrayed decades after his death at sea. A nearly fatal accident as a boy left Stock crippled and intimately acquainted with the frailty of the human body, but it also ultimately led to his career as an artist when one of his physicians recommended painting as an activity he could pursue though paralyzed from the waist down.

The physical and artistic challenges of obtaining an animated likeness from a supine corpse were many, especially if the corpse was marked by disease, decomposing, in a coffin, or even already interred. Handling the corpse was requisite in order to glean accurate measurements, secure the chin so the mouth was closed, or open eyelids to ascertain the color of the eyes. Some families requested a portrait years after someone had died, requiring the artist to depend upon existing likenesses in the form of earlier portraits, miniatures, daguerreotypes, or even to paint the portrait based upon verbal descriptions and resemblances to other family members, much as a forensic artist functions today. The strong psychological desire for a good likeness overcame many shortcomings in the actual portrait, and journal entries written by grateful family members often express satisfaction following much doubt voiced during the emotionally fraught process.

After 1839, when photography was introduced in the United States, memorializing the dead soon came within grasp of even the most humble household. At first, the daguerreotype functioned much as the posthumous portrait had: an attempt to cheat death of its final insult—being forgotten. In its intimate scale and the concept that the very light emanating from a body was captured on the silver plate, the daguerreotype was closely related to mourning miniatures in lockets that often enclosed the hair of the beloved. Once the full potential of the “sunbeam” art was recognized, it altered the conventional formula of the painted posthumous portrait. The emphasis shifted from the “sleeping” image to the reality of the corpse whose “hue of death” could not be disguised, and finally to the act of mourning itself. “Secure the shadow ere the substance fade” became the sales pitch of the daguerreotypist and paid homage to the time-honored trope of the shade as a substitute for corporeal presence.

It is difficult now to conceive of a time when images of family and friends were precious and few, and when a life might indeed end without ever having been visually recorded. Posthumous portraits and postmortem daguerreotypes may inspire a morbid fascination, yet one cannot help but hear them whisper through the years, “Remember me,” because, as photographer Matthew Brady declared in 1856, “You cannot tell how soon may be too late.”

Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America will be on view at the American Folk Art Museum from October 5, 2016, to February 26, 2017. The accompanying catalog, by exhibition curator Stacy C. Hollander, with an essay by Gary Laderman and a Foreword by Anne-Imelda Radice, will be available for purchase in October, 2016 at shop.folkartmuseum.org.

----

Stacy C. Hollander, deputy director for curatorial affairs and chief curator at the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. John Hannavy, ed. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Photography (New York: Routledge, 2013), 1044.

3. Samuel Sewall. Diary of Samuel Sewall: 1674–1729. V. 1 [-3]. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1879. Vol. II, 170.

4. See Phoebe Lloyd, “A Death in the Family,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 78, No. 335 (1982): 2–13 for an in-depth analysis of this painting.

5. Ibid., 5.

6. Ibid., 7.

7. https://animalsmattertogod.com/2012/06/03/goldfinch-symbol-for-resurrection. Accessed May 22, 2016.

8. Dr. Phoebe Lloyd, “A Young Boy in His First and Last Suit,” The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin, 64 (1978–1980): 104–111. © MIA, accessed May 25, 2016.

9. Joan R. Brownstein, advertisement in Maine Antiques Digest (February, 2004): 5-D.

10. Jane Quackenbush Austin to Alice Schryver Austin and Barton Slade, Salem, February 11, 1883: http://mv.ancestry.com/viewer/df8a5bd0-5bd2-478a-9680-abb7f4119366/75523014/38316756141, accessed May 25, 2016.

11. Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2008. https://www.rpharms.com/museum-pdfs/g-teethingtreatments.pdf, accessed May 25, 2016.

12. Stanley B. Burns, with Elizabeth A. Burns. Sleeping Beauty II: Grief, Bereavement and the Family in Memorial Photography: American & European Traditions (New York: Burns Archive Press, 2002): fig. 1.

13. Doris Thatcher, letter of July 19, 1971, in NGA curatorial files. Thatcher additionally notes that each child of the Catlin family was portrayed with the same scene behind them. The artist is thought to possibly be Joel Parks, a little-known Tioga painter who lived in the vicinity. Quoted in Deborah Chotner, American Naïve Paintings (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1992), 550.