Unrivaled: Hispanic Society Museum & Library

The Winter Show Loan Exhibition

|  | |

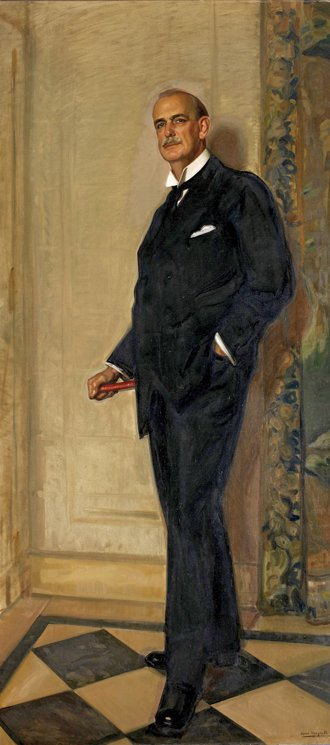

Left Fig. 1: José María López Mezquita (1883–1884), Archer Milton Huntington, 1926. Oil on canvas, 92½ x 42⅛ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (A3071). Right Fig. 2: Exterior of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library on Audubon Terrace in Upper Manhattan. | ||

| |

Fig. 3: Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660), Camillo Astalli, known as Cardinal Pamphili, Rome, Italy, 1650–1651. Oil on canvas, 24 x 18⅞ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (A101). |

The Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York, is the only institution in the world with collections that span over four thousand years of the arts, literature, and cultures of the Iberian Peninsula. Artifacts dating from the sixteenth century through the twentieth century from Latin America and the Philippines are also represented. Exceptional examples from the collections are included in Unrivaled, the loan exhibition at the Winter Show 2020, curated by Philippe de Montebello and Peter Marino. The forty-nine objects in the exhibition include paintings and sculpture by the great Spanish masters; decorative arts from Spain, Latin America, and the Philippines; photographs from Chile and the Philippines; Spanish medieval manuscripts; along with manuscript charts and maps of the Mediterranean, North America, and Peru.

The Hispanic Society embodies the vision of Archer Milton Huntington (1870–1955), a native New Yorker, who from his youth dreamed of founding a museum and library centered on the countries of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking peoples (Fig. 1). Archer Huntington was the only child of the railroad and shipping magnate Collis Potter Huntington (1821–1900), and Arabella Duvall Huntington (1850–1924). Following the death of her husband, Arabella Huntington formed one of the most important art collections of her era, which included Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer and Gainsborough’s Blue Boy. Archer Milton Huntington’s life-long passion for Hispanic culture began with the purchase at age twelve of George Borrow’s The Zincali: An Account of the Gypsies of Spain (1841). For the next two decades he dedicated himself to the study of Spanish art, history, and literature, all the while collecting books, manuscripts, and photographs. Following the death of his father in 1900, he started acquiring paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, and antiquities, with a view to placing them in the public museum and library he envisioned.

|  | |

Left Fig. 4: Anonymous, Cuzco School, The Presentation in the Temple, Peru, 1700s. Oil on canvas, 37¾ x 40⅛ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library (LA2190). Right Fig. 5: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), Pedro Mocarte, Spain, ca. 1805. Oil on canvas, 30¾ x 22½ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (A1890). | ||

|

Fig. 6: Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923), Children on the Beach, Spain, 1908. Oil on canvas, 32 x 41⅝ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (A2138). |

|  | |

Left Fig. 7: Egyptianized Reshef, Phoenician, Mérida, Badajoz, Spain, 600s BC. Bronze, H. 9⅝, W. 2 in. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (D958). Right Fig. 8: Albarello (Pharmacy Jar), Manises, Valencia, Spain, ca. 1390. Tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt and luster, H. 11¼, W. 4⅞ in. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (E575). | ||

In 1904, Huntington founded the Hispanic Society of America and acquired land in Upper Manhattan, on Broadway between 155th and 156th Streets, now known as Audubon Terrace. A Beaux-Arts building for the museum and library was completed by 1906, and opened to the public in 1908. Over the next two decades Huntington worked to create the premier institution in the United States dedicated to the arts and culture of the Spanish-speaking world (Fig. 2). Since Huntington’s death in 1955 the collections have been significantly enriched through donations and acquisitions, and over the past twenty years, the acquisition of major works from Latin America has been a priority.

| |

Fig. 9: Aquamanile in the Form of a Portuguese Female Dragon (Coca), Portugal, 1625–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware, H. 9⅛, W. 4¾, D. 6¾ in. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (LE2409). |

Unrivaled offers a panorama of the Hispanic Society’s riches. Even though the Hispanic Society currently has a major traveling exhibition, Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, that includes over two hundred of its most important works, Unrivaled is not short on treasures. Paintings by the great Spanish masters figure prominently in the loan exhibition, with works by El Greco, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Goya, and Sorolla. The portrait of Camillo Astalli, known as Cardinal Pamphili (Rome, 1650–1651), by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660), is undoubtedly the star (Fig. 3). In it, the full pictorial genius and amazing technique of Velázquez are on full display. Acquired by Huntington in 1904, this portrait was his first major acquisition for the museum.

The Presentation in the Temple (1700s), from Peru’s Cuzco School (Fig. 4), bridges the gap between fine and decorative arts, with its two-dimensional overlay of floral and foliate designs in gold leaf and spectacular carved gilt wood frame ornamented with hundreds of iridescent shell segments in swirling patterns set amongst cherubs and flowering vines. Another highlight is the portrait of Pedro Mocarte (circa 1805–1806) by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828) (Fig. 5). The portrait of his friend Pedro Mocarte, a professional singer at the Toledo Cathedral, depicted in the costume of a bullfighter, exemplifies Goya’s work before the Peninsular War (1807–1814).

With one of the finest collections of paintings, gouaches, and drawings by the Valencian master Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923), the exhibition would not be complete without one of his prized beach scenes. Children on the Beach (1908) (Fig. 6), a major work from the peak of his career exemplifies his reputation as the “painter of light.”

|  | |

Left Fig. 10: Manila Galleon Chest, Philippines, ca. 1700. Narra wood, brass, and iron, H. 24, W. 36⅛, D. 21⅝ in. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (LS23760. Right Fig. 11: Maya (Altar Plaque), Alto Peru, Bolivia, 1700s. Silver, chased, and repoussé, H. 16⅞, W. 17⅞, D.1¾ in. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (LR2392). | ||

Sculpture also figures prominently in Unrivaled, with fine examples from the ancient cultures that inhabited the Iberian Peninsula, along with two extraordinary works by Spain’s first major woman sculptor. The Phoenicians had established colonies in southern Spain by the 8th century BC. A remarkable Phoenician small bronze of a striding figure depicts the ancient Semitic god of war Reshef (600s BC), as assimilated by the Egyptians and the Phoenicians (Fig. 7). The Roman marble sculpture, Portrait Head of a Julio-Claudian Imperial Princess, perhaps Julia Drusilla (30-50 CE), typifies the sculpture produced in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica. The astoundingly realistic polychromed terracotta sculptures, Head of Saint John the Baptist (Madrid, 1692–1706), and Head of Saint Paul (Madrid, 1692–1706), by Luisa Roldán (1652–1706), attest to her brilliance as a sculptor, for which she was appointed sculptor to the royal court of kings Charles II and Philip V.

The earliest ceramics in the exhibition come from the Bell Beaker culture of southern Spain. The black pottery lidded bowl, footed bowl, and dish with incised geometric decorations filled with white paste date from 2400–1900 BC. In the collection of the Hispanic Society, superb examples abound of tin-glazed lusterware produced by Muslim potters working in Manises (Valencia) during the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. An albarello, or pharmacy jar, (ca. 1390) (Fig. 8), displaying Islamic decorative motifs that include pseudo-Arabic script in the top and middle bands, dates from the earliest period of production. In the sixteenth century, Portugal became famous for its blue and white tin-glazed earthenware. A rare example is the aquamanile, or jug-type vessel, in the form of a Portuguese female dragon (1625–1650) (Fig. 9), which at first glance appears to be sphinxlike, but actually represents a coca, the female dragon of Portuguese and Galician folklore that fights Saint George.

|

Fig. 12: Map of the Ucayali River, Peru, 1808–1812. Ink and color on paper, 22⅞ x 62¼ inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (K60). |

A Philippine chest (circa 1700) of narra wood, a rare survivor from the Manila Galleon Trade (Fig. 10), is carved with Asian floral and foliate motifs, combined with lions and birds. Such chests were made in the Philippines and used to transport luxury goods on the Spanish trading ships that voyaged between the Philippines and Spain. The chests were later sold to the viceregal elite to ornament their palaces. The pair of silver plaques from Bolivia known as mayas (1700s), were displayed upright on altars to reflect candlelight (Fig. 11). At the center is a double-tailed siren, surrounded by undulating stems of stylized sunflowers and tails of serpent dragons, all popular motifs found on the silverwork from Alto Peru.

| |

Fig. 13: Obder W. Heffer Bisset (1860-1945),Mapuche Cemetery, Chile, ca. 1890. Albumen print photograph, 8⅞ x 11 inches. Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York (GRF 178568.46). |

The Hispanic Society’s collection of manuscript nautical charts and atlases spanning the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries is recognized as one of the finest in the world. Two historically significant charts from North and South America on display at the Winter Show reflect two different worlds. Elizabeth Bermingham’s impressive Chart of the Atlantic Coast of North America from South Carolina to Florida and the Eastern Caribbean (1727) is the earliest nautical chart produced by a woman in the Americas. The spectacular Map of the Ucayali River (Peru, circa 1808–1812) depicts one of the most remote regions of Peru in the Amazonian rainforest (Fig. 12). Prepared by Franciscan missionaries with the assistance of indigenous artists, the map graphically portrays the fauna of the Ucayali, an inland department of Peru located in the Amazon rainforest, and its indigenous peoples in scenes of hunting and fishing.

Some of the most recent acquisitions of the Hispanic Society are represented by a group of captivating albumen photographs from the Philippines and Chile dating from the 1840s to the 1920s. The haunting image of a traditional Mapuche cemetery (circa 1890) in south central Chile (Fig. 13) was captured by the Canadian photographer Obder W. Heffer Bissett (1860–1945), a founder of ethnographic photography in Chile. In the photograph a Mapuche elder is surrounded by chemamülles, monumental wooden crosses and statues that reflect the spirit of the deceased.

|

The Hispanic Society Museum & Library seeks every opportunity to offer access to its world-renowned collections. The Winter Show offers the latest opportunity to introduce some of its treasures to new audiences with Unrivaled: Hispanic Society Museum & Library, presented at New York City’s Park Avenue Armory, January 24–February 2, 2020. For more information, visit www.thewintershow.org or www.hispanicsociety.org.

Mitchell A. Codding is the executive director and president of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library, New York City.

This article was originally published in the 20th Anniversary (Spring/Summer 2020) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.