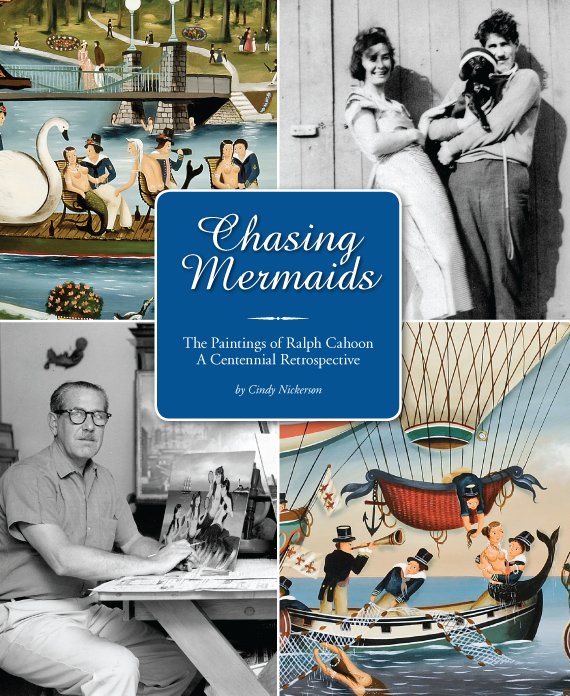

Chasing Mermaids: The Paintings of Ralph Cahoon, A Centennial Retrospective

|

| Fig. 1 (upper right): Martha and Ralph Cahoon shortly after their marriage in 1932. Also pictured above: (upper left) detail of figure 5; (lower right) detail of figure 7; (lower left, detail) Ralph at work in his studio at his and Martha's Cape Cod home, ca. 1960. |

Whatever high jinks his mermaids and sailors may be up to in the foreground, paintings by celebrated Cape Cod folk artist Ralph Cahoon typically have a background of sea and sky. Often there's a clipper ship or two sailing on the glassy water and a lighthouse on a promontory at the horizon. Ralph Eugene Cahoon Jr. was born in such a setting on September 2, 1910. Located on the Cape's elbow, his hometown of Chatham, Massachusetts, boasts more than sixty miles of coastline and, until 1923, had four lighthouses in operation.

| |

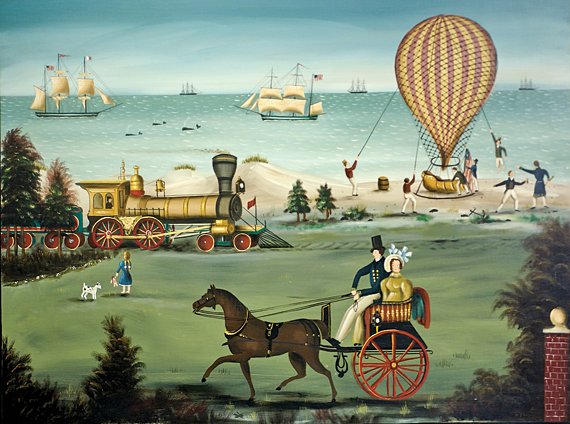

| Fig. 2: Blanket chest with Cape Cod R.R. Steam Engine decorated by Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), ca. mid 1940s-early 1950s. Oil on wood, H.17-1/2, D. 43, W. 17-3/4 in. Area of decoration, 12-1/4 x 37 inches. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Robert C. Eldred Co. |

In addition to enjoying activities like fishing and clamming as a boy, Ralph had an early love of drawing. In his senior year he took a correspondence course in cartooning, and after high school attended the School of Practical Art in Boston (later the Art Institute of Boston). He hoped to pursue a career in the commercial arts, but discontinued after two years for financial reasons.

In 1930, he met Martha Farham, a pretty young woman five years his senior. Within two years they were married (Fig. 1), and in 1935 their only child, Franz, was born. Martha had been apprenticed to her father, Axel Farham, a furniture decorator, and she began teaching Ralph the trade shortly after their union. He quickly mastered designs from the Scandinavian, Pennsylvania-German, and American folk traditions, and they made a decent living selling antiques and restoring and decorating furniture (Fig. 2).

Following World War II, the Cahoons purchased and renovated a late-eighteenth-century Georgian Colonial in the village of Santuit, now part of Cotuit on the Cape. With fourteen rooms, it easily accommodated a studio and galleries as well as the family's residence. Ralph now undertook more ambitious projects, decorating large case pieces such as secretaries and cupboards. The Cahoons incorporated their first mermaids, borrowed from a dower chest illustrated in Frances Lichten's Folk Art of Rural Pennsylvania (1946), into a design for a blanket chest. The Cahoons were never slavish copyists; they changed details and often combined elements from more than one source. Eventually, they began to paint some original scenes. For Ralph, these often involved sailors and mermaids.

|

| Fig. 3: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Transportation, ca. 1955. Oil on masonite, 32-1/2 x 42-1/4 inches. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques. |

|

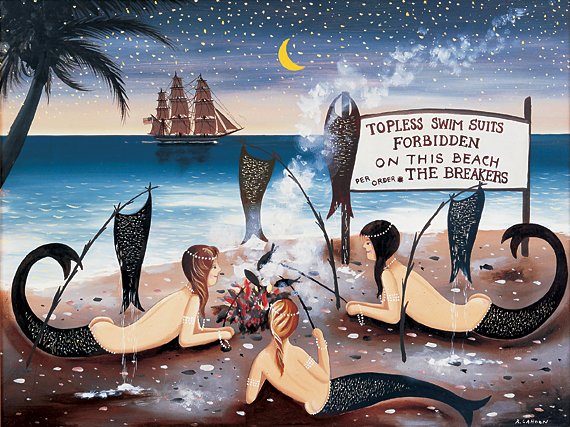

| Fig. 4: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Topless Swim Suits Forbidden, 1965. Oil on masonite, 15-1/2 x 20-1/8 inches. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. |

The Cahoons always credited heiress, art collector, and New York Mets co-founder Joan Whitney Payson with sparking their transition from furniture decorators to primitive artists. In the early 1950s, charmed by their designs, she advised them to paint scenes that could be framed. In 1953, when Payson opened the Country Art Gallery on Long Island, she invited them to send her some paintings. When they obliged, she telephoned asking for more, excitedly reporting that everything had sold. The following year, the Cahoons had their first show at the gallery, also a sell out. The gallery director, Clarissa Watson, recalled years later, "They were an immediate sensation—Martha for her delicate and sensitive beaches and birds and shells, and Ralph for his wickedly humorous mermaids and sailors."1

As the Cahoons expanded their painting repertoire, they generally selected themes in keeping with the period from about 1790 to 1875 when American folk art flourished. With their backgrounds as antiques dealers, and Ralph's particular interest in history, they tried to authentically represent such elements as architecture, ships, and garments, even when there was a fanciful mermaid in a painting.

Ralph wasn't solely identified with mermaids in the beginning. In Transportation (Fig. 3), he incorporated several modes of vintage conveyance, including a hot-air balloon that hasn't quite gotten off the ground. Ralph also tried his hand at some farm scenes in the style of Edward Hicks. "We…feel quite confident that as many paintings as you ever do in this mood would be enthusiastically received by the people who come to our gallery," Watson wrote encouragingly in late 1955.2 By early 1956, however, excitement at Country Art Gallery had changed focus. After two of Ralph's mermaid paintings sold, clients began requesting notification "the moment" more came in. Watson closed a letter with: "There just suddenly seems to be a run on mermaids!"3

|

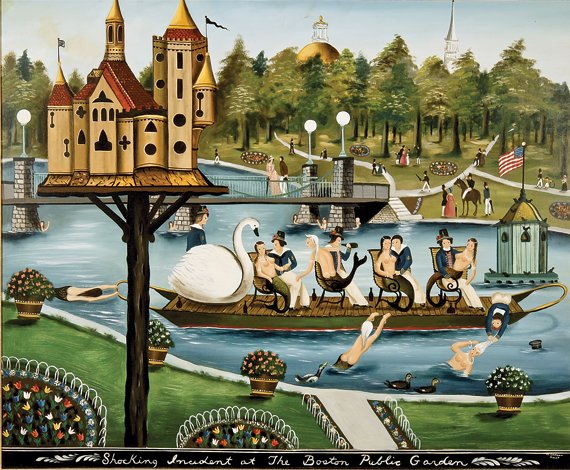

| Fig. 5: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Shocking Incident at the Boston Public Garden, 1960. Oil on masonite, 32 x 39-1/2 inches. Courtesy of Robert C. Eldred Co. |

|

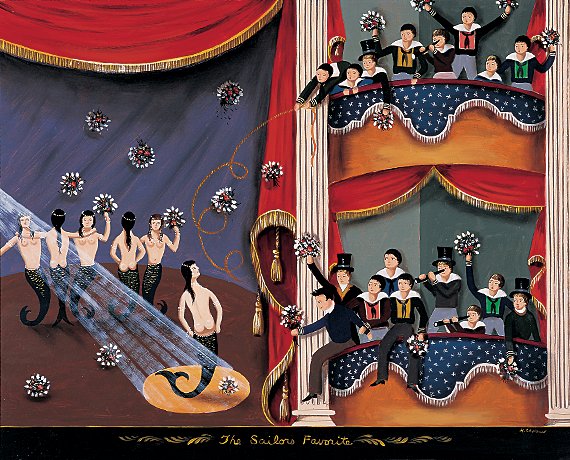

| Fig. 6: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), The Sailors' Favorite, ca. 1961. Oil on masonite, 23-1/2 x 29-1/2 inches. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. |

|

| Fig. 7: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Fishing for Mermaids, ca 1960s. Oil on masonite, 30 x 40 inches. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques. |

The earliest of Ralph's mermaids reflect his sense of fun, but the draftsmanship is less polished, the compositions simpler and less unified than his later works. His early mermaids act more like the mermaids of myth, consorting with sailors on tropical islands. Soon, though, Ralph was having them ride a whale or upset a boat, or encountering predicaments, such as getting caught in fishnets. Recalling his ancestors who toiled at sea, Ralph once said: "I like to think that in all their grim trade, they chased the mermaid from time to time."4

In 1959, the Cahoons began a relationship with gallery owner George E. Vigouroux Jr., showing with him at the Lobster Pot on Nantucket that summer. A show at Vigouroux's Palm Beach Galleries followed that winter. Their work proved so popular that for several years in the sixties there was a "Cahoon Room" at the Lobster Pot. Palm Beach clients included Lilly Pulitzer and Marjorie Merriweather Post, onetime owner of Topless Swim Suits Forbidden (Fig. 4). The scenes Ralph painted for a Florida audience often include palm trees.

|

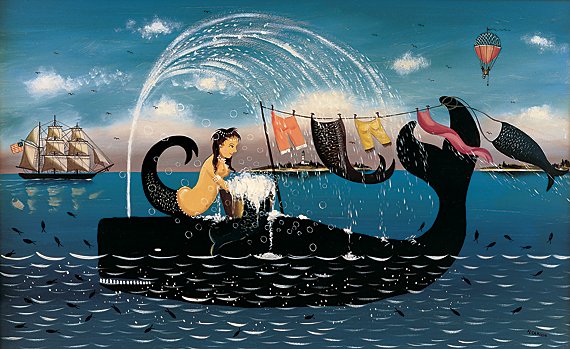

| Fig. 8: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Mermaid's Washday, ca. 1960–1962. Oil on masonite, 16-1/2 x 26-1/2 inches. Private collection; on long-term loan to the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. |

A 1960 exhibition at Vose Galleries of Boston generated considerable publicity and sales and enhanced the Cahoon's reputation. Ralph painted most of the forty-five works (Martha being less prolific due to her responsibilities as a homemaker). For him the show was a watershed, a point where he made a leap forward in the complexity of his work, and his wit and narrative powers show considerable sharpening in the service of his art. Shocking Incident at the Boston Public Garden (Fig. 5), clearly aimed at Boston residents, has the polish and cohesiveness of Ralph's mature style.

Ralph's mermaids were now handling a broad range of activities with ease. They pick apples, harvest wheat, cook and sew, play tennis and ride bicycles. "How can a mermaid ride a bicycle?" a reviewer wrote. "Such is the magic of the Cahoon touch you forget to ask."5 Though Ralph's paintings have been described as "rowdy" and "robust," they have an underlying sweetness that keeps virtually any scene wholesome. There's even a certain innocence about The Sailors Favorite (Fig. 6), a painting done to commemorate the Old Howard, a burlesque theater in Boston.

Over the course of a decade, the Cahoons had shows at galleries in Connecticut, Delaware, Wisconsin, and California. Other galleries tried to establish a relationship with the couple, but Ralph and Martha were already struggling to meet the demands coming from Long Island, Nantucket, and Palm Beach. In addition, they did summer business at their own studio. In 1961, first lady Jacqueline Kennedy arrived there from the Summer White House in Hyannis Port and purchased two of Ralph's paintings.

|

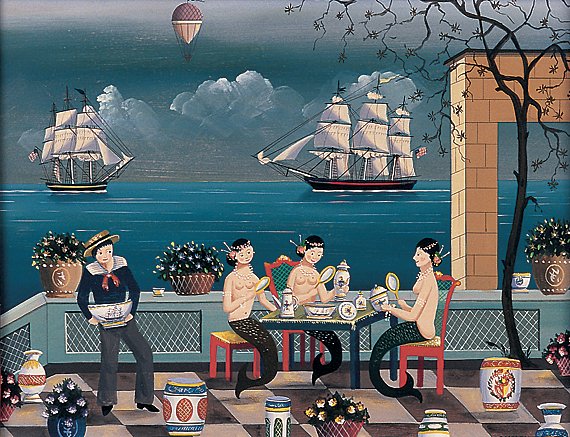

| Fig. 9: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), Oriental Scene. Oil on masonite, 13-1/2 x 17-1/2 inches. Hand-carved antique Chinese export frame. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. |

Next to mermaids, Ralph may be most strongly associated with hot-air balloons, which had a starring role in paintings such as Fishing for Mermaids (Fig. 7). Ralph relished inventing outrageous balloons—shaped like birds or fish, or sporting smokestacks, and probably inspired by antique prints of fantastical imaginary balloons. Ralph also painted many whales, which he stylized to some extent and often used as a stage of sorts, as in Mermaid's Washday (Fig. 8), where a mermaid does her laundry on a whale's back.

Chinese scenes were another specialty. Oriental Scene (Fig. 9) is Ralph's imitation of China trade paintings done by nineteenth-century Chinese artists for the American market. The open architecture, pots of flowering plants on the wall, and the clarity of the style itself are typical of the genre.

As the sixties drew to a close, Ralph and Martha severed ties with their galleries, fairly confident they could sell exclusively from their own studio. Cape resident Josiah K. Lilly III, an heir to the pharmaceutical fortune, was one of the Cahoons most enthusiastic patrons. During the artist's lifetime, Lilly purchased more than fifty of Ralph's paintings. In 1969, Lilly founded Heritage Plantation of Sandwich (now Heritage Museums and Gardens) as a repository for much of his Americana collection. When the Arts and Crafts Museum opened there in 1972, Lilly gave the Cahoons the inaugural show.

|

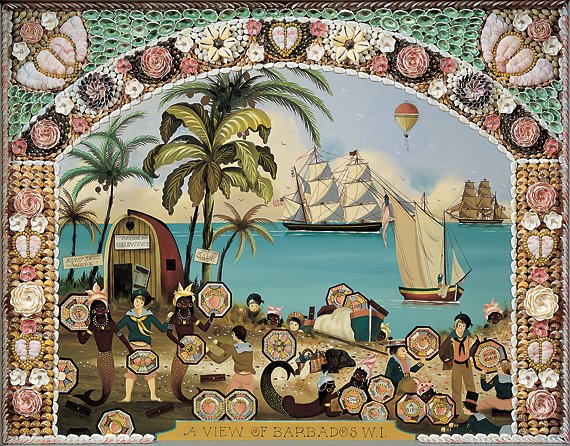

| Fig. 10: Ralph Cahoon (1910–1982), with shellwork by Bernard A. Woodman (1920–1986), A View of Barbados, W.I., ca. 1977. Oil on masonite, 28 x 34 inches. Collection of the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. |

Ralph had struggled with a drinking problem, but in 1976, concerned that it was interfering with his ability to paint, he came to terms with his addiction during a period of hospitalization, returning to work with renewed enthusiasm and even with a new direction of sorts. Through AA meetings, he befriended Bernard A. Woodman (1920–1986), who suffered from a disabling form of arthritis. Encouraged by Ralph, Woodman discovered his talent for making sailor's valentines, and created many with a small round painting by Ralph at the center. Woodman also embellished several paintings with shellwork, including A View of Barbados, W.I. (Fig. 10), which shows sailors purchasing sailor's valentines as souvenirs on the West Indian island.

Ralph was by now getting $1,000 to $3,500 for his more ambitious works. But after his death in 1982 from cancer, values skyrocketed. When Nantucket Incident—which pictures a sailor pushing a mermaid in a wheelbarrow down a cobblestone street—came up for sale at a Cape Cod auction in August 1985, a bidding war broke out between Lilly and a scion of the Mellon family. The work went to Lilly for $32,000.6 The record sale came in 2000, when Nantucket Clambake sold for $179,000 at Rafael Osona Auctions on Nantucket.

Ralph and Martha's one-time home in Cotuit is now the Cahoon Museum of American Art, founded by local art collector Rosemary Rapp and her husband, Dr. Keith Rapp, in 1984. In celebration of the centennial of Ralph's birth, the museum presented Chasing the Mermaids from July 27 through September 19, 2010. For more information call 508.428.7581 or visit www.cahoonmuseum.org.

1. Clarissa Watson to Ralph Cahoon, 25 November 1955, Cahoon Papers, Cahoon Museum of American Art.

2. Watson to Ralph Cahoon, 25 November 1955, Cahoon Papers.

3. Watson to Ralph Cahoon, 8 March, 1956, Cahoon Papers.

4. Mailer for "Paintings by Ralph Cahoon," an exhibition held from November 29 through December 20 [1958] at the Moyer Gallery in West Hartford, Connecticut. Cahoon Papers, Cahoon Museum of American Art.

5. [J. H. Ackerman] "Boston to See Satirical Cape Primitive Paintings." New Bedford Standard-Times (November 16, 1960).

6. Gene A. and Judy Schott, interview with author, August 3, 2009. Gene Schott was the director of Heritage Plantation for many years.

Cindy Nickerson, a former director/curator of the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit, Massachusetts, is the curator of Chasing the Mermaids. She is writing a forthcoming biography about the Cahoons.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|