What To Look For When Buying English Antiques

|

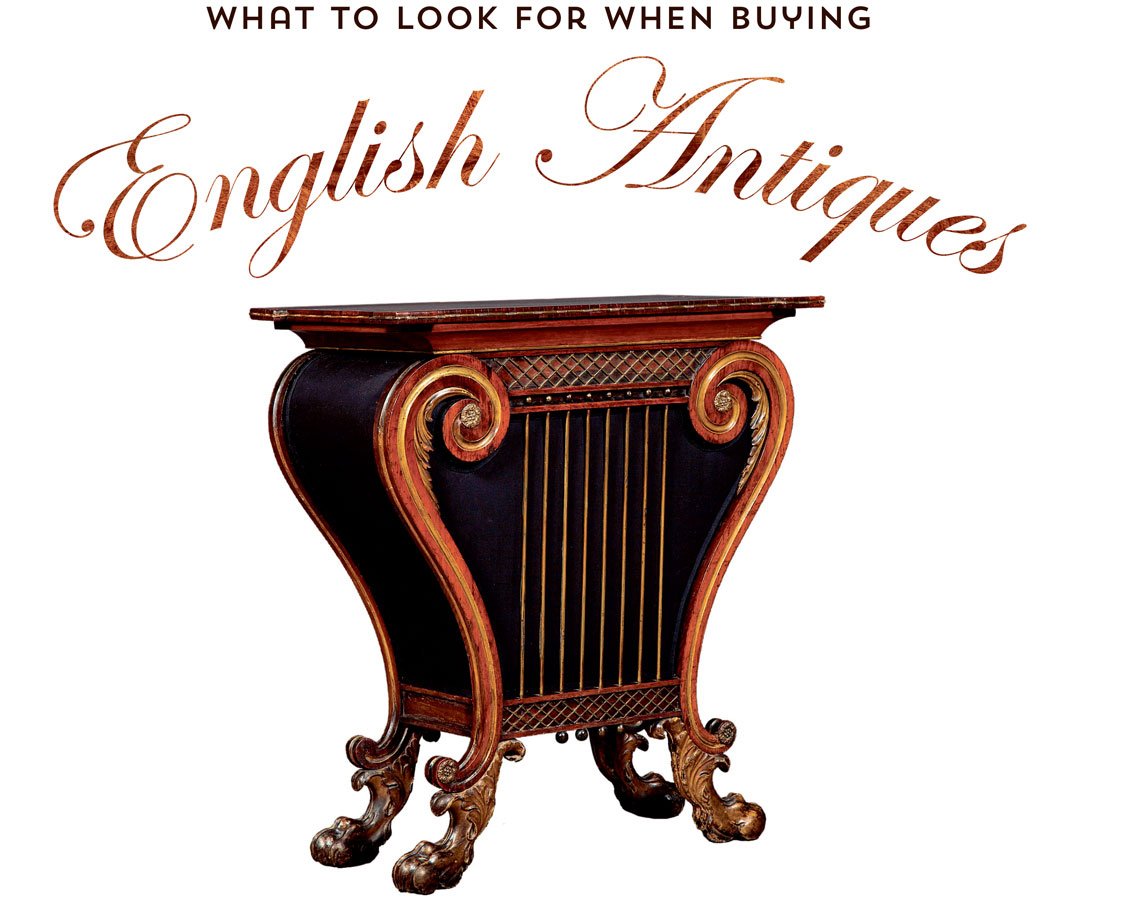

Carlton Hobbs presents this early 19th-century Regency lyre-form rosewood and parcel gilt console table. What a lovely design and what wonderful condition. This piece transcends time. |

by Clinton Howell

In the recent sale of Ann and Gordon Getty’s furniture in New York, there was a level of English and Continental furniture, quality-wise, that hasn’t been seen for a good long while. The top lot in the sale, an early George III mahogany breakfront cabinet by William Vile with exquisite carving by Sefferin Alken, created for Queen Charlotte in 1761 for St. James’s Palace is a good case in point. Estimated at $600,000–$1,000,000, it sold for $2,700,000, and it is possibly one of the finest pieces to come onto the auction market in the last twenty years. The English antique furniture trade is still vibrant and has pieces that may not be quite as rare, but which in some ways rival what could be found at the Getty sale, and wonderful pieces can be found at a wide range of price points. What do dealers, such as myself, look for in a piece and what should the buyer look for? As a rule, you should be guided by five essential elements or aspects of a piece of furniture.

|

|

| |

Peacock's Finest is offering a Georgian oval satinwood Pembroke table, circa 1790. One of the more useful pieces of English furniture is the Pembroke table, originally used as a tiny dining table, especially for breakfast or tea. Satinwood is just a stunning timber. Antique Satinwood is native species from the Caribbean and a member of the citrus family. It has been off the market for centuries now, nearly all harvested for fine furniture. |

First and foremost is the design of a piece. Design elicits an emotional reaction almost immediately. It repels or attracts straightaway. It doesn’t mean you can’t learn to love a piece, but the identical design made to a different scale can alter your perception. It is important to spend time trying to figure out why you think what you think, as the makers usually had a reason for making an item in a certain fashion. For example, a demilune sideboard, which will usually be deeper than a D-shape or rectangular sideboard, was likely made for a neoclassical interior. Go to the Metropolitan Museum and check out the Lansdowne House dining room and you will see that a demilune sideboard is ideal for that space. It reflects the theme of the room. This is true for furniture of all eras of furniture design. You can subject almost every piece of furniture to this sort of examination and as you become familiar with 18th, 19th and 20th-century design, you will learn why certain things were made. While there are no hard and fast rules about what will work in a particular setting, the principles of scale and balance have everything to do with creating a beautiful interior. And of course, the familiar adage about first knowing the rules before you can break them applies here as well.

|

From Hyde Park Antiques, an extremely rare, circa 1815–1820, Regency games table attributed to George Bullock, in oak and ebony with a chessboard, backgammon board, and green leather-lined surface for cards. Weird and wonderful by one of England’s more innovative designer/makers who died way too young. Bullock furniture is always interestingly designed. |

|

|

|

Left: Michael Lipitch has a great collector’s piece, an especially fine Chippendale period serpentine front chest, dating to 1765. The serpentine chest has a wide variety of iterations: three drawers or four, straight or shaped bracket feet, shaped sides, or straight? This chest has wonderful Cuban mahogany in untouched condition, original lacquered gilt bronze handles and beautiful proportions. Right: From Wick Antiques comes this unusual Amboyna cupboard by Gillow & Co, dated 1874. The choice of timbers that cabinetmakers had at hand in the 19th century was phenomenal given how far it had to travel, Indonesia or possibly Burma, in this case. A functional cupboard, but with such great timber, you want the piece to be seen. The gray marble top is original. |

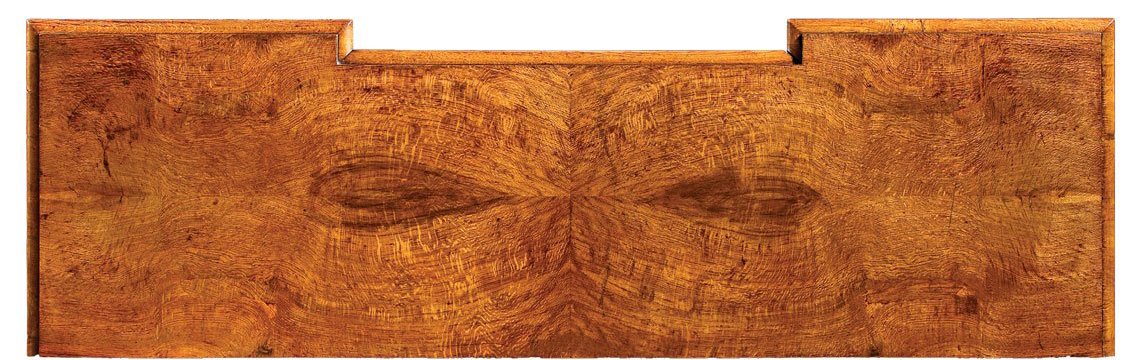

The second thing to look for is color. Usually, you don’t have to look very hard to find color — the piece has it or it doesn’t. Color is inherent in the quality of timber used in the manufacture. A straight-grained piece of maple, for example, will fade a bit and have a little color, but it will not have the intensity of rock or bird’s eye maple with its swirling grain patterns. This is because the refraction of light is variable according to the grain direction. But color is also “patina”. Patina is a multitude of things that begins with how wood is affected by time and continues with maintenance, usage, abuse, resurrection, dirt, pollution and sunshine. The piece of straight-grained maple, on its own mundane, can look extraordinary with the addition of patina.

| Here is a beautifully figured George II burr walnut and parcel gilt mirror, dating to 1730. Really good walnut as seen in this mirror is a rarity as more often than not, it has been sanded and re-polished. This mirror is dry-stripped as well, a technique used to get back to the original gilding. From Michael Pashby Antiques. | |

| ||

|

Condition is the next aspect. A piece in bad condition got that way for a reason. Was it poorly made to begin with or was it just badly abused? There is poorly made 18th-century furniture, just as there is badly designed 18th-century furniture. There are a couple of things that will denote condition pretty quickly — is there any color, for example? No color would indicate that something has been done that should not have been, such as replacements, or stripping and sanding. Other things such as new hardware, new legs, new anything indicates that there has been an issue. It may be completely resolved, but it is nice to know that it existed in the first place — it’s sort of like knowing the mileage of the used car you are buying, except perhaps that you want more mileage, rather than less.

|

George II drop leaf mahogany tables suffer endless damage along the hinges unless the craftsmanship is good. This table is relatively unscathed and a deep rich color, with each section a single board. Carved knees and ball and claw feet on tables this size, over 5½ feet in diameter, are rare. From Clinton Howell Antiques. |

|

A very attractive Pollard oak mid-19th century sideboard from Loveday Antiques. Pollard oak started to be used quite heavily in the early to mid-19th century. Pollard oak is not a species, rather its distinctive swirling grain is created by vigorous and repeated pruning creating a burr, which is then harvested and cut for veneers. It is a sophisticated look as is the style of the sideboard. |

|

|

|  | |

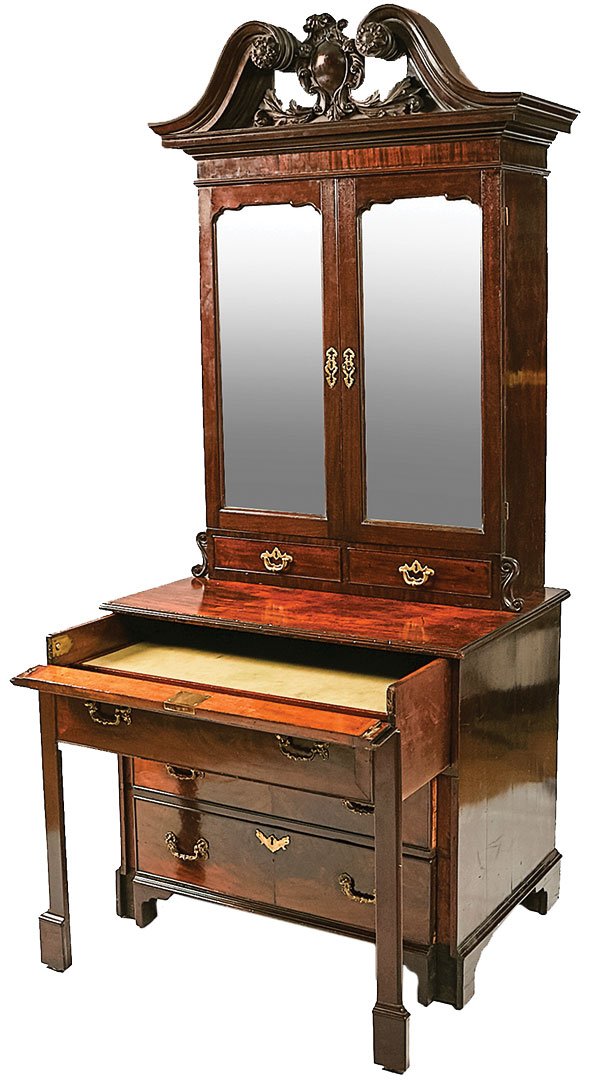

From O’Sullivan Antiques comes this estate-made 18th-century Georgian flame mahogany cabinet/secretaire. A fascinating piece of furniture; Irish furniture is abundant in distinct design conceits and the craftsmanship is usually superb. The mahogany used in Ireland is always dark, rich in tone, and very heavy. | ||

Craftsmanship, of course, relates to condition, just as condition relates to color. This aspect is usually pretty straightforward, but not always. If you want to see the greatest cabinetmaker to have lived, I recommend going to the Metropolitan Museum website to look at the David Roentgen furniture. It will give you an idea of how well a piece can be made. There are best practices in good craftsmanship such as understanding how best to counteract the expansion and contraction of wood that occurs with levels of humidity, but in reality, the best way to deal with the issue was for the cabinetmaker to have used properly dried timber. Ergo, when examining a piece for condition and finding lots of splits and cracks, the likelihood is that the craftsman used timber that wasn’t properly dried. That is a condition issue related to craftsmanship.

|

The serpentine chest remained popular through the last quarter of the 18th century, and Charlecote Antiques has a lovely late 18th-century Hepplewhite period piece with very fine inlay. The top on this chest shows great originality and craftsmanship as well as excellent color. |

|

The most perfect history will include the invoice and correspondence between the maker and his client. This doesn’t happen often. Furthermore, English furniture does not, as a rule, come with signatures or labels — it wasn’t done that often in the 18th century. It changed a bit in the 19th century and large-scale manufacturers such as Gillows recognized the value of this fairly early on. But those examples are rare. Items shipped abroad also had labels or signatures, but that is also fairly rare. Hence, a lot of provenances are either about the succession of dealers who may have sold a piece or the house a piece is thought to have been in, or possibly made for.

|

Clinton Howell Antiques has a rare set of 8 George II mahogany dining chairs with a terrific provenance to both a house and a maker. The chairs were made circa 1740 for Sir Herbert Pakington, for his ancestral seat Westwood Park, granted to the Pakington family by Henry VIII. Attributed to the great cabinetmaker Samuel Soho, they are of superb craftsmanship with extremely substantial and fine carving, and in extremely fine condition as well. |

|

|

An 18th-century dresser base with a scalloped apron. There is a lovely whimsical quality to the scalloped base of this oak dresser. Oak can bring warmth into a room, particularly in candlelight. From Yew Tree House. |

The rationale behind liking a piece of furniture is both subjective and logical — this conundrum bows to the fact that not everyone has the same taste and there will always be disagreements about design and color. You can like something that belonged to your grandmother even if it is something you would never go out and buy and this brings me to the final point. Furniture should be a pleasure to live with, it should fulfill a function and, if it’s antique, bring a sense of both warmth and history into a room. I love mahogany, but I also live with walnut, oak and rosewood as well as a pair of 1920s Jansen brass bookshelves. I wouldn’t mind having some yew wood, amboyna or birds eye maple, but it will have to wait as will my purchase of a Roentgen piece. Maybe someday!

Clinton Howell is a New York City-based antique dealer in very fine English antique furniture and decorative objects, serving a world-wide clientele of collectors, designers and museums alike. The Clinton Howell Antiques collection of fine English furniture can be viewed at The Gallery at 200 Lex powered by Incollect.