Egyptian Revival

American

The Egyptian Revival style, alongside Gothic and Classical Revival, gained significant popularity in American decorative arts during the 19th century and extending into the 1920s. Featuring iconic motifs such as obelisks, hieroglyphs, the sphinx, and pyramids, this aesthetic influenced various artistic mediums including architecture, furniture, ceramics, and silverware. Offering a departure from traditional styles, Egyptian motifs provided an exotic allure.

Originating from Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign in 1798–9, a surge of interest in Egyptian art and culture emerged. Publications like "The Description of Egypt" and the translation of the Rosetta Stone further fueled this fascination, leading to the integration of Egyptian-inspired elements in architecture and art across Europe and America. Early American examples include architectural landmarks like the original Library of Congress and the Washington Monument.

The second wave of Egyptian Revival in the U.S. around 1870 coincided with a post-Civil War curiosity in foreign cultures, particularly those of the Middle East and North Africa. This era saw a fusion of Egyptian motifs with traditional Western forms, notably in furniture design. Gilt bronze fittings resembling sphinxes, Egyptian scenes in textiles, and geometric plant renderings became characteristic features of this style.

Beyond architecture and furniture, Egyptian motifs found their way into smaller decorative arts. Academic publications and archaeological expeditions continued to popularize iconic Egyptian symbols like the sphinx and hieroglyphics, influencing objects such as Tiffany & Co.'s mantel clock. As Egypt remained in the public eye through events like the opening of the Suez Canal and cultural productions like Verdi's opera "Aida," Egyptian iconography persisted in decorative arts, including ceramics, silverware, and jewelry.

While direct translations of ancient Egyptian art declined in popularity, designers adapted more artistic motifs, as seen in Louis Comfort Tiffany's Laurelton Hall. Combining lotus blossoms, reeds, and geometric mosaics, Laurelton Hall exemplifies a broader trend of eclectic adaptation of Egyptian forms into modern decorative movements.

Despite the rise of other decorative styles like Aestheticism, Arts and Crafts, and Art Nouveau at the turn of the century, Egyptian motifs remained relevant, particularly in the work of artists like Marie Zimmermann. However, it wasn't until the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 that Egyptomania resurged, influencing the Art Deco movement, which dominated decorative arts until the mid-1930s.

Originating from Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign in 1798–9, a surge of interest in Egyptian art and culture emerged. Publications like "The Description of Egypt" and the translation of the Rosetta Stone further fueled this fascination, leading to the integration of Egyptian-inspired elements in architecture and art across Europe and America. Early American examples include architectural landmarks like the original Library of Congress and the Washington Monument.

The second wave of Egyptian Revival in the U.S. around 1870 coincided with a post-Civil War curiosity in foreign cultures, particularly those of the Middle East and North Africa. This era saw a fusion of Egyptian motifs with traditional Western forms, notably in furniture design. Gilt bronze fittings resembling sphinxes, Egyptian scenes in textiles, and geometric plant renderings became characteristic features of this style.

Beyond architecture and furniture, Egyptian motifs found their way into smaller decorative arts. Academic publications and archaeological expeditions continued to popularize iconic Egyptian symbols like the sphinx and hieroglyphics, influencing objects such as Tiffany & Co.'s mantel clock. As Egypt remained in the public eye through events like the opening of the Suez Canal and cultural productions like Verdi's opera "Aida," Egyptian iconography persisted in decorative arts, including ceramics, silverware, and jewelry.

While direct translations of ancient Egyptian art declined in popularity, designers adapted more artistic motifs, as seen in Louis Comfort Tiffany's Laurelton Hall. Combining lotus blossoms, reeds, and geometric mosaics, Laurelton Hall exemplifies a broader trend of eclectic adaptation of Egyptian forms into modern decorative movements.

Despite the rise of other decorative styles like Aestheticism, Arts and Crafts, and Art Nouveau at the turn of the century, Egyptian motifs remained relevant, particularly in the work of artists like Marie Zimmermann. However, it wasn't until the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 that Egyptomania resurged, influencing the Art Deco movement, which dominated decorative arts until the mid-1930s.

Egyptian Revival

Antique Pair of English Egyptian Revival Candlesticks

H 11 in W 3 in D 6 in

$ 3,500

Access Trade Price

Egyptian Revival

Monumental Gand Tour Bronze Garden Sphinx

H 22 in W 20 in D 39 in

$ 4,000

Access Trade Price

Egyptian Revival

Pair of English Regency Egyptian Style Terra-Cotta Table Lamps

H 46 in W 5 in

$ 12,500

Egyptian Revival

Royal Doulton Egyptian Revival Porcelain Jardinière

H 8 in DIA 10 in

$ 2,150

Access Trade Price

Egyptian Revival

19th-Century French Flame Mahogany Napoleon Empire Period Mantel Clock

H 11.81 in W 7.48 in D 6.69 in

$ 8,678

Egyptian Revival

Regency, Floor Lamp, Egyptian Motif, Gilt Metal, Bronze, 1990s

H 60 in W 10 in D 10 in

$ 3,800

Egyptian Revival

18th Century Continental Terracotta Egyptian Revival Sphinxes, a Matched Pair

50% Off

Sale Price: $ 7,200

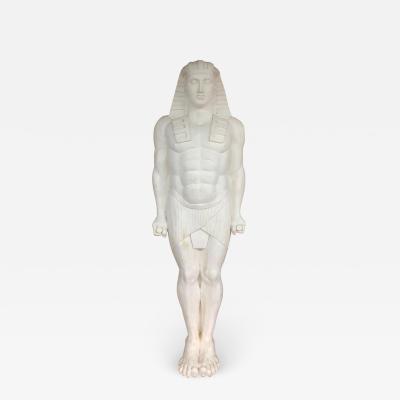

Egyptian Revival

Monumental Egyptian Revival Plaster on Fiberglass Sculptures

H 79 in W 25 in D 13 in

$ 8,500

Egyptian Revival

Pair of French Mahogany Egyptian Revival Chairs, 19th century

H 31 in W 21 in D 18 in

Egyptian Revival

A pair Napoleon III Egyptian imperial porphyry urns and covers

H 22 in DIA 57 in

$ 23,790

Egyptian Revival

Grand Tour Alabaster Bust of Egyptian Woman

H 8 in W 4 in D 5 in

$ 985

Access Trade Price

Egyptian Revival

Egyptian Revival Art Deco Style Pair Vase

H 16 in W 13 in D 10 in

$ 1,900

Access Trade Price

Loading...

Loading...