Youth and Beauty

Art of the American Twenties

Few moments in American cultural history are as recognizable as the 1920s—their mere mention conjures flappers, Fords, and skyscraper cities. And yet, American artists responded to their dizzying modern world with art that evoked stillness, clarity, and order. With Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties, the Brooklyn Museum celebrates the work of sixty-seven painters, sculptors, and photographers who responded to the cultural upheaval in an era framed by the aftermath of the Great War and the onset of the Great Depression. Confronted with an environment newly altered by a sweeping wave of mechanization and urbanization, they coined a lean modern realism in an effort to process a barrage of stimuli, and to create something authentic and inscribed with the adaptive struggles of the individual. In the new twenties realism, liberated modern bodies resonate with classical ideals, the teeming modern city is rendered empty and silent, and still life is pared to an essentialized clarity.

Throughout the twenties, American artists, as never before, addressed the physical fact of the human body. Conditioned by theories of “healthy-body culture” and Freudian psychoanalysis, and by the body-centric advertising and motion-picture industries, this generation of artists embraced physical perfection and sexual liberation, and represented the human form unmasked and at close range. Equally mindful of the pernicious effect of machines, their figural art was deliberately natural in its emulation of the whole, graceful forms of Italian Renaissance models. While paralleling the contemporaneous European style known as the “call to order,” these figure subjects speak less of post-war recuperation than of liberation—the freed American body, vigorously physical and candidly sensual. Para-doxically, American figurative art of the twenties is also insistently restrained—stilled, weighty, and sober—especially in the context of the accelerated energy of a new, urban-industrial consumer society. Lorser Feitelson’s Diana at the Bath (Fig. 1) is one of many works whose modernity rests in an uneasy reconciliation of liberation and restraint. Acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1924, the canvas features contoured and choreographed figures inspired by the expressive exaggerations of Italian Mannerism and rendered in chalky tonalities that recall Renaissance frescoes. The bodies, however, are lithe, athletic, and modern.

The exposed body was the source of both euphoria and apprehension during the twenties. Images of the uncovered and uncorseted female body were ubiquitous in ads, and in films. Yet even proponents of liberalized mores promoted the idea of a “right” kind of body presence: actively physical and frankly sensual, but vibrantly healthy as well. It was the age of Freud in America, and repression was a bad word, but flagrant moral slackness was still censured. George Wesley Bellows likely had Freud in mind when he painted Two Women (Fig. 2), his homage to Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love (Galleria Borghese, Rome), the Renaissance masterwork in which a nude and a clothed figure are paired to contrast pure love (unclothed) and its worldly counterpart. In Bellows’s twenties response, the pair embody the vying impulses of sexual openness and repression, with the nude figure radiantly lit in the well-recognized parlor setting of Bellows’s rural Woodstock home.

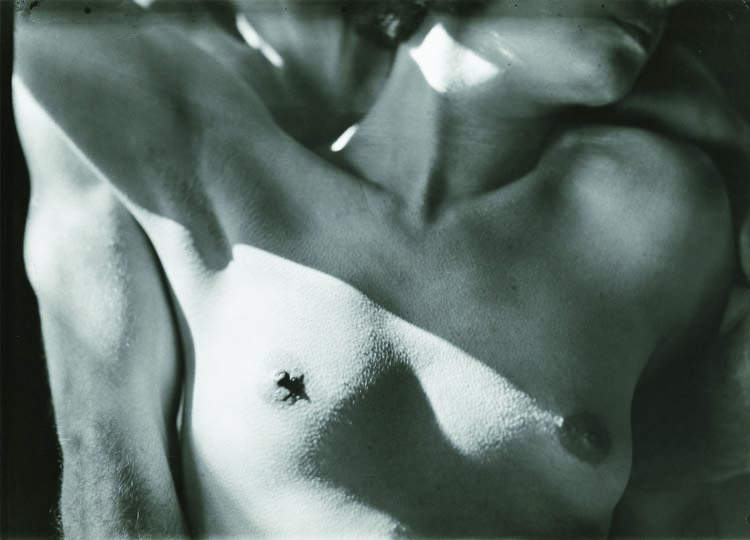

- Fig. 3: Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883–1976) Nude, 1923

Gelatin silver print, 615⁄16 x 9½ in.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson, Purchase © (1923), 2010 The Imogen Cunningham Trust,

www.ImogenCunningham.com.

Throughout the twenties this “right” physical presence was associated with the notion of the clean—a concept also embraced by twenties artists and writers to denote the honesty of their artistic expression—especially in reference to the physical. Twenties artists represented physical intimacy as a closely observed proximity to the body, or to natural forms that served as bodily surrogates. Their subjects and their creative processes were thus both natural and authentic, and antithetical to the routinized physical existence of industrial workers, urban commuters, and bourgeois consumers. The West Coast photographer Imogen Cunningham’s Nude (Fig. 3), a striking example of forthright sensuality, represents the linked bodies of photographers Margrethe Mather and Edward Weston. A daring subject for any artist in 1920s America, Cunningham’s superbly choreographed composition embodies the equation of vivid physicality and creative agency.

Throughout the 1920s, the idea of clean but forthright physicality came to play in a plethora of images of swimmers and bathers, featuring bodies that are racy but “pure.” The hybrid realism of Joseph Stella’s The Birth of Venus (Fig. 4) recalls the linear delicacy of Italian Renaissance art while presenting a svelte modern woman with arms uplifted to unabashedly expose her ecstatic form and porcelain skin. This liberated pose recurs countless times in twenties fashion magazine ads hawking streamlined underthings, deodorants, and depilatories to women seeking the perfection required by revealing new styles. It was an ideal conceit for a painting completed for Carl Weeks, the De Moines inventor of a face powder that earned millions. If the sensuously revealed body was de rigueur in American art of the twenties, evocative flora just as often provided sensuous body surrogates. In her vividly hyper-real California Data (Fig. 5), Henrietta Shore merged natural forms—including the popular calla—to create an animated, generative hybrid.

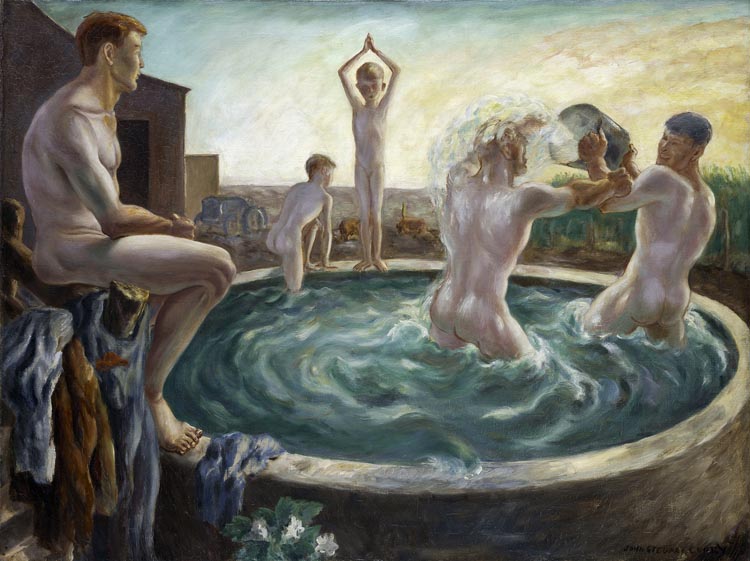

- Fig. 6: John Steuart Curry (American, 1897–1946)

The Bathers, circa 1928

Oil on canvas, 30⅛ x 40⅛ in.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Purchase: Acquired with a donation in memory of George

K. Baum II by his family, G. Kenneth Baum, Jonathan Edward Baum, and Jessica Baum Pasmore, and through the bequest

of Celestin H. Meugniot. © Estate of John Steuart Curry.

Photo: Jamison Miller.

Along with the sensual body, twenties artists celebrated the heroic human form even as modern America presented a daunting challenge to its physical integrity. Overstimulated and depleted bodies were increasingly the norm in a country that was, for the first time, more urban than rural, and where physical routines were being reformulated by automated labor and modern eating habits. While drawing on classical and Renaissance art, these works invested in the bodily wholeness that had been revalued in the aftermath of the recent war. John Steuart Curry drew on his rural Kansas boyhood for his The Bathers (Fig. 6), in which a beautifully muscular nude surveys a halcyon scene of boys sporting in a cattle tank. The painting would have been unthinkable, however, in isolation from a broader artistic milieu that included Paris, where Curry witnessed the revival of classical nudes among leading modernists, and Westport, Connecticut — where this work was painted — whose community of urbane, Jazz Age New York transplants liberalized his Midwestern views about the modern body.

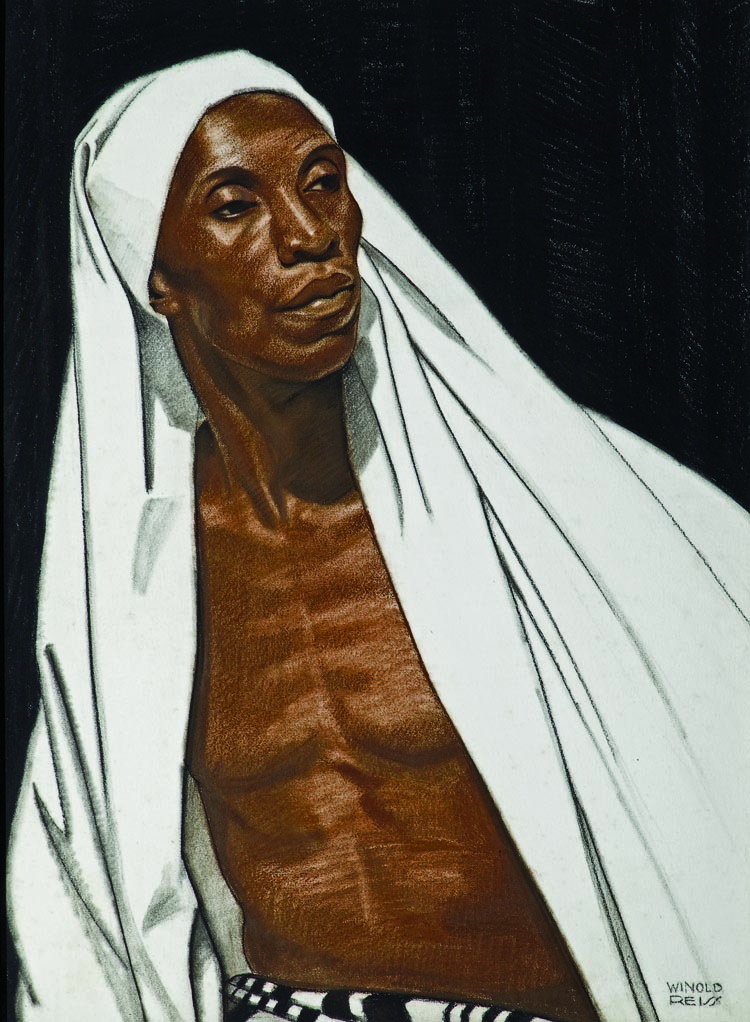

The heroic black body received unprecedented attention in American art of the twenties, largely in response to the rising influence of urban African-American culture. Black Prophet (Fig. 7) was one of the Harlem portraits completed by Winold Reiss for a special 1925 issue of the journal Survey Graphic, entitled Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro. The sitters were chosen by New Negro Movement leaders including Alain Locke, who were eager to recalibrate the image of black Americans in the context of this dynamic, cross-cultural “race capital.”

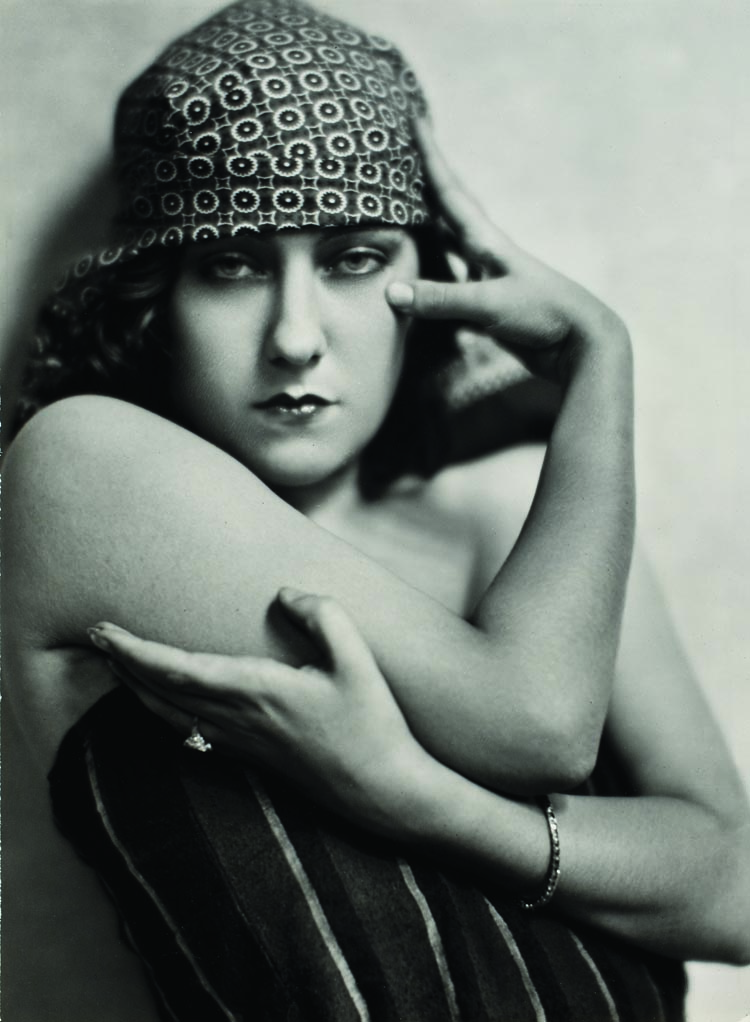

For the countless portraits that constituted a vital aspect of twenties art, artists took their cue from advertising and the movies, and fixed on the close-up as the portrait form of choice. No matter how aesthetically elevated, the modern close-up portrait participated in exacting new beauty standards and even mimicked the self-scrutiny that underpinned them. Photographers in particular, empowered by their cameras, aimed for proximity and clarity as markers of visual truth. It was, of course, entirely in keeping with the age of Freud that an external likeness was considered to only hint at the complex psyche of any individual. One popular trope that emerged during the twenties to suggest a beautiful woman’s depth was to represent her holding her face, masklike, as if to signal both self-invention and resistance. In his captivating portrait of the young Gloria Swanson (Fig. 8), Nickolas Muray recorded the sultry perfection of Swanson’s face as though it were held delicately in place by her sensuously bare shoulder and precisely placed hand.

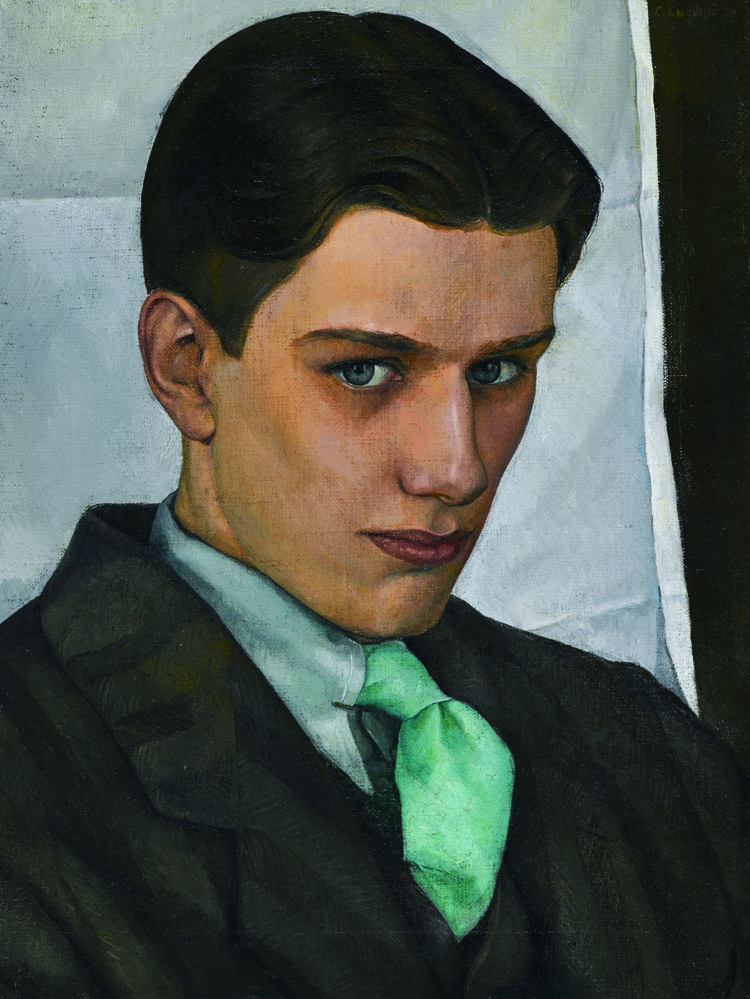

Luigi Lucioni’s magnetic likeness of Paul Cadmus (Fig. 9) is perhaps the quintessential twenties portrait. Presenting the budding young painter as a polished advertising artist, it also celebrated the shared passion of two young moderns for Italian Renaissance art. Within a modern, close-up format, Lucioni referred to the distilled and evocative quietism of frescoes by Piero della Francesca and Andrea Mantegna in the flawlessly outlined and modeled form of his sitter’s head, set against the backdrop of a creased, white cloth.

American artists and writers, unsettled by the “new” world of the twenties, shifted uneasily between a brave embrace of the exciting, urban-industrial realities of scale, speed, and sound, and a visceral revulsion toward the same. Unlike their writer counterparts, however, visual artists resisted representing the increasingly contested borders of city and country, where progress relentlessly challenged an older order. They were inclined to edit out the crowds and conflict, and only rarely represented the inhabitants of the American environment.

In the rare instances when young American artists represented figures in the landscape, the people tend to appear ill at ease in their surroundings, or distanced as spectators. The experience of the American landscape was indeed altered in the twenties by the new ubiquity of automobiles and ninety-six thousand miles of new national highway. While the automobile is virtually absent from American art of the decade, it is implicated. Few works suggest the new sense of discomfiture in the face of the modern landscape as effectively as Guy Pène du Bois’s People (Fig. 10), in which the artist described a well-dressed crowd in an open landscape, where they appear to be drawn toward a vague, but vividly bright, expanse.

Artists who sought to interpret the proliferating forms of the urban-industrial environment applied their preferred spare and idealized realism whose hallmarks were lucidity, order, and an evocative austerity. The latter quality was regularly praised for its resonance with the naïve art of an increasingly distant, early American past, and with that era’s natural cadences and simple values. Critics indeed challenged artists who represented the functional logic and clean geometries of the Machine Age to overcome modern engineering’s denial of the natural or the intuitive. The reductive realism that most artists embraced transformed the daunting modern environment into something more contained and knowable; it provided a visual stalling tactic while cultural critics debated the impact of these altered places on their human inhabitants. In George Ault’s Brooklyn Ice House (Fig. 11), one of those works praised by critics for its pleasing blend of modernism and naïveté, the spare, closed forms are hermetic and the palette off-key; the lyrically decorative plume of black smoke offers the picture’s only sign of life.

Inspired by twenties poet William Carlos Williams’s famous imperative “no ideas but in things,” and his insistence on a “local” idiom, American still life painters embraced the genre as a means of testing the pleasures and tensions of modern, everyday life—from the challenge of industrialization to remade codes of beauty and behavior. Manufactured soup cans and cocktail shakers began to compete with the natural forms of eggs and apples for their place in precisely choreographed formal arrangements that harmonized or bared prevailing frictions. With its “pre-Pop” billboard-style boldness, Gerald Murphy’s Razor (Fig. 12) suggests the crest of a modern American man. As heir to the Mark Cross company, Murphy was attuned to the design of life’s accoutrements. He borrowed from the new, reductive French aesthetic of Purism to celebrate American machine-age design and to express his own modern self-fashioning.

Throughout the twenties, artists struggled to express in newly fashioned, modern forms their authentic, personal experience of a culture that had been dramatically remade. Whether in vividly described body imagery, in vertiginous visions of skyscrapers, or still life featuring the novelties of the modern American table, they evinced their modernity, above all, in a desire for direct engagement, a faith in the potentiality of youth, and a belief in the sustaining value of beauty.