The Reeves Collection of Ceramics at Washington and Lee University

The Reeves Center at Washington and Lee University, in the small town of Lexington in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, holds a treasure trove of historic ceramics. Designed to be an educational resource, the collection is used to teach students and the broader community about the design, production, trade and use of ceramics.

Housed in a temple-fronted faculty residence built in 1842 (Fig. 1), the Reeves Center contains galleries house Chinese export porcelain, Chinese armorial porcelain, and British and Continental European ceramics made between 1500 and today. The collection began with a gift from Euchlin and Louise Herreshoff Reeves in 1967. Euchlin, a 1927 graduate of Washington and Lee’s law school, had contacted the school in 1963 with an enigmatic postcard that read, “[S]omeday I may wish to make a donation of a work of art to the University. Are you interested?”

- Fig. 3: Platter or stand, Meissen Porcelain Factory, Meissen, Germany, 1736-1741. Porcelain. L. 19¾ inches Gift of Euchlin and Louise Herreshoff Reeves. Photography by Kevin Remington.

This stand is from the so-called Swan Service, one of the largest and most important dinner services made at the Meissen factory, which was the first in Europe to make true, hard-paste porcelain. The service, which contained over three thousand pieces, was made for Count Heinrich von Brühl. Each piece is decorated with swans molded in relief, which gives the service its name.

The “work of art” was a collection of over two thousand pieces of Chinese export porcelain and British and Continental European ceramics that Euchlin and Louise had assembled, first independently and then together after their marriage in 1941. An unconventional couple, Louise was a sixty-six-year-old divorcee when she met the thirty-eight-year-old Euchlin at a ceramics collectors’ club meeting in early 1941, in Providence, Rhode Island.2

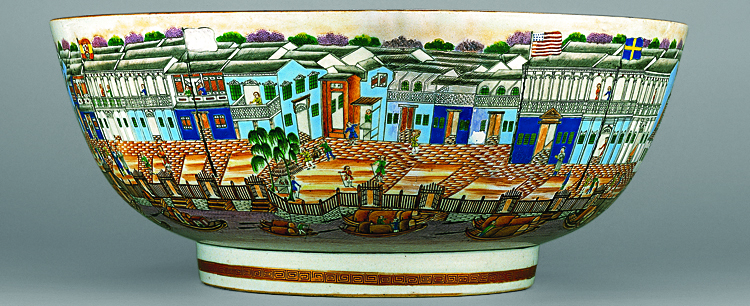

Theirs was typical of ceramics collections assembled in the middle decades of the twentieth century, and reflected an interest in American history as well as an appreciation for the aesthetic qualities of ceramics made in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Reeveses were especially interested in collecting pieces associated with historical figures, such as George Washington, Paul Revere, and merchant Elias Hasket Derby. They were also drawn to pieces decorated with patriotic emblems, such as the Great Seal of the United States and the American flag. One of their prize pieces was a rare hong bowl decorated with a panoramic view of the Western trading settlement in the Chinese port of Canton that includes the American flag (Fig. 2).

The Reeveses also collected large quantities of British and Continental European ceramics, focusing on pieces from noted factories like Meissen (Fig. 3) and those with American connections, such as the French porcelain State Service acquired by Mary Todd Lincoln for the White House in 1861 (Fig. 4).

- Fig. 4: Eggcups, made in France and decorated by E. V. Haughwout & Co., New York, 1861. Porcelain. H. 3¾ inches. Gift of Louise Herreshoff and Euchlin Reeves. Photography by Kevin Remington.

This is one of the twenty-four eggcups that were part of a 666-piece dinner, dessert, and breakfast service commissioned by Mary Todd Lincoln for use in the White House in 1861.

- Fig. 5: Salad bowl, China, 1784. Porcelain. L. 10⅛ inches. Gift of the Edward H. Thompson family. Photography by Ellen Martin.

Decorated with insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati, this salad bowl is from a 302-piece service commissioned by Samuel Shaw, the first American merchant to go to China. It was bought by George Washington, and eventually descended to his step-great granddaughter, Mary Custis, and her husband, Robert E. Lee.

- Fig. 7: Coffee cup, China, about 1710. Porcelain. H. 2¾ inches. Gift of H.F. Lenfest and Beverly M. DuBose III. Photography by Kevin Remington.

This cup is part of a set made for Harry Gough, who made his fortune from the China Trade. He began his career as a cabin boy at the age of eleven, and by 1707 he was captain of his own ship. The profits from his voyages allowed him to retire from the sea. As part of his program to establish himself as a member of the gentry, Gough commissioned several sets of armorial porcelain.

The Reeveses’ collection came to Washington and Lee upon Louise’s deaths in 1967 (depite the fact that Euchlin was some thirty years Louise’s junior, he predeceased her). The Reeves Center opened 1982, and since then the collection has continued to grow, as curators and generous donors add pieces that fill gaps and make the collection a more comprehensive and useful teaching tool. The collection now numbers over four thousand objects, ranging from Neolithic Chinese pots to contemporary studio ceramics.

Best known for its Chinese export porcelain, the collection is perhaps the fourth or fifth largest in the United States. With pieces made between 1500 and 1900, the collection provides an overview of the range of forms and designs of export porcelain made for the European and American markets over four centuries. It is especially rich in pieces made for the American market in the decades after the establishment of direct trade between the United States and China in 1784.3

Among the highlights, and especially appropriate for Washington and Lee University, are eight pieces from the service decorated with the insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati that was owned by George Washington and later by Robert E. Lee (Fig. 5). Commissioned by Samuel Shaw, the first American merchant to go to China, Washington bought the 302-piece service in 1786, and used it in the presidential mansions in New York and Philadelphia and at Mount Vernon. Decorated with the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, which was named for the ancient Roman hero who served Rome in time of need without expectation of reward or permanent power, the service probably helped reinforce Washington’s image as a selfless patriot and new type of leader.

- Fig. 8a: Platter, China, 1760–1770. Porcelain. L. 14⅝ inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by Herbert McKay. Photography by Kevin Remington.

Chinese export porcelain was mass-produced by workmen and women, each completing a different step in the production. The platter in figure 8 is incomplete, with only part of its design executed in underglaze blue. For some reason, it lacks the overglaze enamels that would have been added by a different set of workers to complete the design. By contrast, the platter in figure 8a was completed, showing what the finished design would look like.

- Fig. 9a: Coffee cup and saucer, China, 1811. Porcelain. D. of saucer: 5 inches. Gift of Bruce C. Perkins in honor of James Whitehead. Photography by Kevin Remington.

During the early nineteenth century, French porcelain, like the plate decorated with a border of classical figures on a colored ground from a service made for John and Isabella Brown of Baltimore and Philadelphia, was the most fashionable fine ceramic available in America. Chinese porcelain, having lost its role as a style leader, began to follow, and Chinese copies of French porcelain began to be made, like the coffee cup and saucer made for Mrs. Benjamin Chew of Philadelphia. Mrs. Chew ordered the service in 1811 through her nephew, Benjamin Chew Wilcocks, a China Trade merchant, and included with her order “patterns” that were no doubt sketches of dishes similar to the French porcelain plate.

Following Washington’s death, the service passed to his step-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, and from him to his daughter, Mary, and her husband, Robert E. Lee. Confiscated by the U.S. government during the Civil War, the service was returned to Lee’s children at the turn of the twentieth century. Few pieces of export porcelain are as intimately connected with such major figures and events of the nation’s first hundred years.

Pieces decorated with coats of arms—an ancient form of personal identification and a mark of family pride—another strength of the Chinese export collection—were popular on Chinese export porcelain from about 1700 until well into the nineteenth century. Armorial porcelain was especially popular in Anglo-American society, with an estimated five thousand services made for English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and British North American individuals. The main display in the armorial gallery is the David Sanctuary Howard Collection of Chinese armorial porcelain coffee cups, which contains almost six hundred coffee cups decorated with coats of arms (Figs. 6, 7), which was assembled by David S. Howard, the leading authority on armorial porcelain. He chose coffee cups because they allowed “the maximum amount of information [in terms of coats of arms] in the minimum amount of space.” With cups dating as early as 1710 and as late as 1860, and with every border pattern found on Chinese export porcelain during that period represented, it may be the most comprehensive collection of armorial porcelain in existence.

The Reeves Center has deliberately sought out pieces that are useful in teaching about ceramics design, production, and trade. An unfinished platter that illustrates the process by which export porcelain was manufactured (Fig. 8), while not the most aesthetically pleasing object in the collection, when paired with a completed example (Fig. 8a), is an invaluable tool in understanding how porcelain was decorated.

Though the British and Continental European ceramics collection is not as well known as the Chinese export holdings, it contains a wealth of examples that illustrate the range of fine earthenwares, stonewares, and porcelains made in the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Many of the pieces illustrate the influences that Chinese export porcelain had on European ceramics, which in turn influenced Chinese export porcelain. By the early-nineteenth century, French porcelain was the most fashionable fine ceramic available in the United States, and China Trade merchants and Chinese potters responded by producing pieces whose shape and decoration was inspired by French wares. A typical example is a Chinese export coffee cup and saucer with neoclassical figures on a yellow ground, whose design was clearly inspired by contemporary French porcelain (Figs. 9, 9a).

In many ways, the newest piece in the collection symbolizes the multiple stories the ceramics in the Reeves Collection tell. American Pickle (Fig. 10), by the contemporary ceramic artist Michelle Erickson, is an attempt to understand how pickle stands were made by Gousse Bonnin and George Morris’s American China Manufactory in Philadelphia in the early 1770s, while also offering a commentary on the vast influence that Chinese blue-and-white porcelain has had on European and American ceramics. The original Bonnin and Morris pickle stand was inspired by similar stands made by English potters who were themselves inspired by Chinese blue and white porcelain. It is also a reminder that the West’s dependence on products “made in China” dates back to the sixteenth century, when direct trade between China and Europe began.

- Fig. 10: American Pickle, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Va., 2007. Porcelain. L. 8 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by Herbert G. McKay. Photography by Gavin Ashworth.

This sculpture is a commentary on the global economy of the twenty-first century and on the United States’ continued dependence on products “made in China.” It is a copy of a stand made about 1770 by Gousse Bonin and George Morris’s American Porcelain Manufactory in Philadelphia, which itself copied English porcelain, which in turn was inspired by Chinese blue and white porcelain, and as such reflects the vast influence that Chinese blue and white porcelain has had on European and American ceramics.

Ron Fuchs II is the curator of the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.

2. Whitehead’s A Fragile Union, tells the story of Euchlin and Louise Herreshoff Reeves and how their collection came to Washington and Lee.

3. Highlights of the Chinese export porcelain collection have been published in Thomas Litzenburg’s, Chinese Export Porcelain in the Reeves Center Collection (London: Third Millenium Press, 2003).