Norton Simon and the House of Duveen

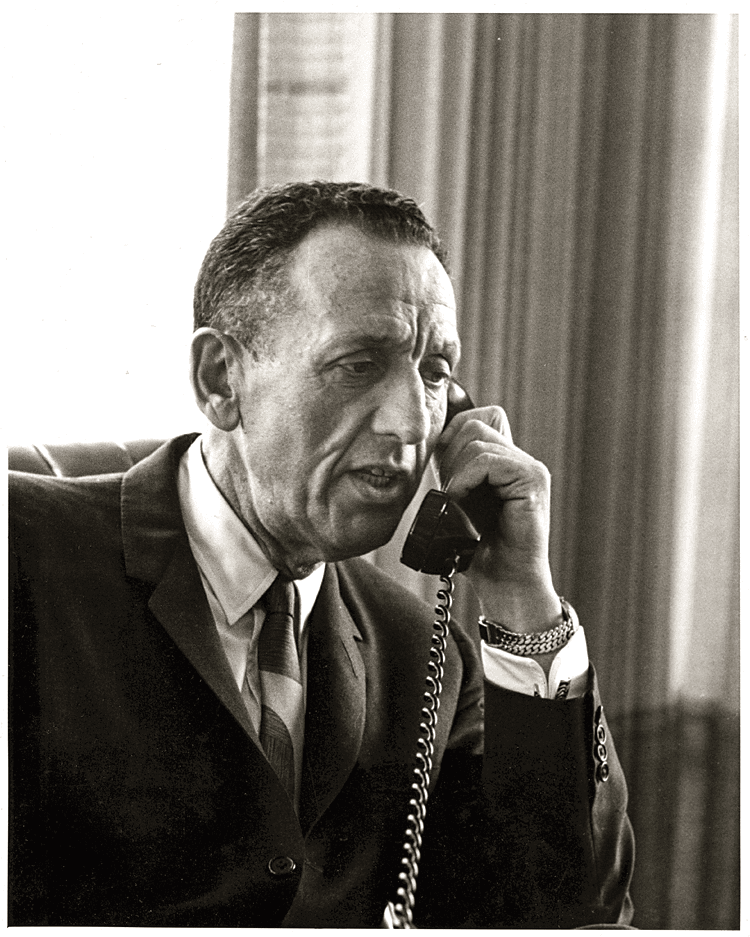

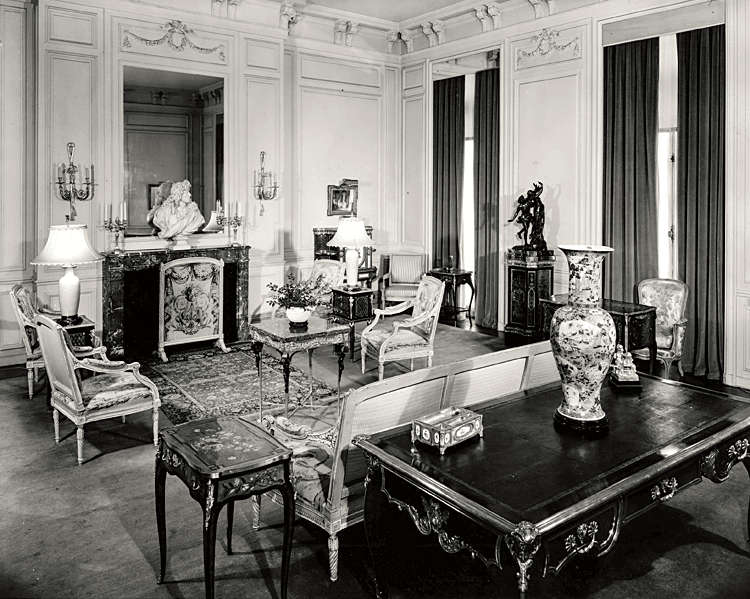

One wonders what his thoughts were when, in 1965, Norton Simon (Fig. 1) signed an agreement with Edward Fowles (Fig. 2) to purchase the legendary Duveen Brothers Gallery, including its massive stock of decorative arts, paintings, and sculpture, as well as its important library and stately galleries at East 79th Street in Manhattan (Fig. 3). Simon had been collecting art—primarily nineteenth-century paintings—for a decade, and had neither the space nor the staff to undertake such a major acquisition. His close ties to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where he was a member of the board, as well as speculation that he would build a museum in Fullerton, California, where his company was headquartered, are faint signs that his drive to amass a collection of art was not only for his own personal gratification. Simon was a keen observer of the business of running a museum, and he was already displaying his prowess as a master of negotiations with art dealers and at auctions. The Duveen acquisition must have been tantalizing for someone like Simon. With this single action, he and his foundations became the owners of more than 800 objects of art; he was only familiar with fewer than twenty of the works.

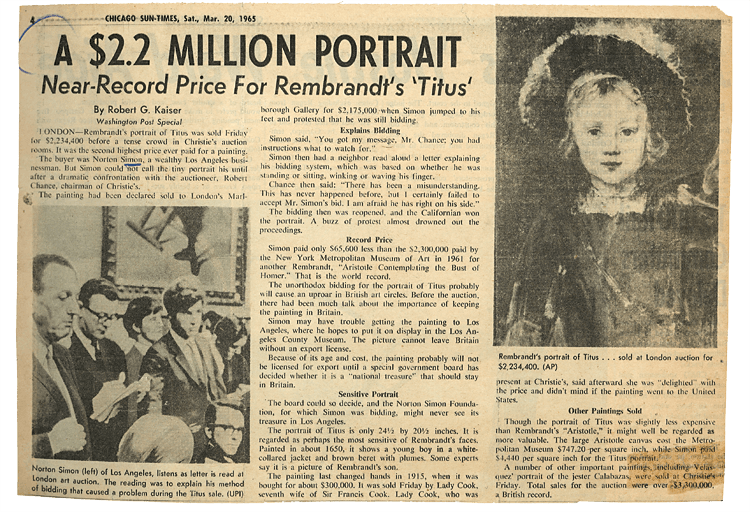

Speculation remains regarding Simon’s drive to own art. Was it the sheer need to possess a thing of beauty? Or was he more interested in art as an investment? Juxtaposed with his purchase of one year later—Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Boy (originally thought to be an image of the artist’s son Titus)—it is impossible not to think that Simon was enjoying his newfound notoriety as one of the major players on the art market (Fig. 4), far afield from his more obscure days as a tomato and orange juice canning magnate.

His initial foray into collecting came when, like other famous collectors—Getty, Huntington, Frick, Morgan, and Gardner, among them—he wanted to outfit his home and corporate offices with art that reflected his newfound wealth. But there comes a time when a collector of this caliber realizes that their acquisitions will outlast them, and so begin to contemplate the future. In purchasing the Duveen stock, Simon was acquiring the contents of a gallery that, more than any other, had influenced the way Americans collected art, and some of whose clients had gone on to found the nation’s foremost public and private museums, including the National Gallery of Art, The Frick Collection, and the Huntington Library and Art Collections.

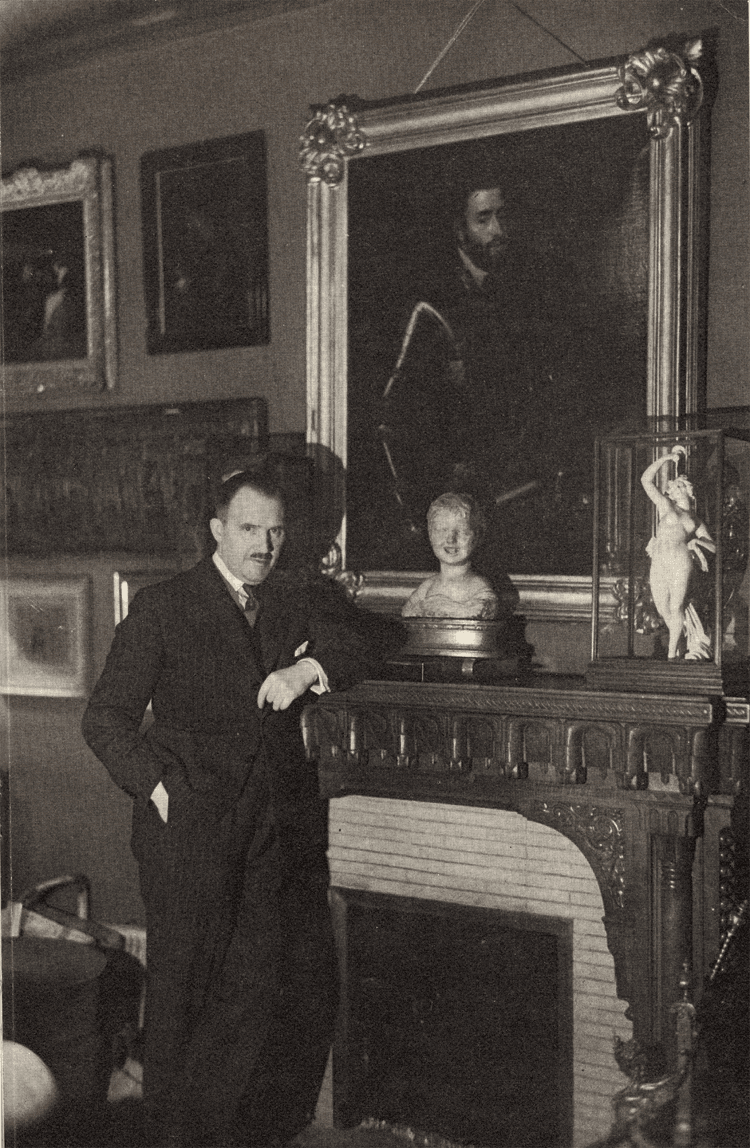

The House of Duveen, as it was often called by its employees, was largely the success of Joseph Duveen (Fig. 5), who had inherited the firm as a small but successful family business dealing in art that had begun with his father, Joel, when he came from Meppel, in Holland, to London, in 1866. Under Joseph’s extravagant personality and guidance, with his father and uncle’s help, Joseph opened additional branches of the firm of Duveen in Paris and New York (Fig. 6).

Joseph Duveen personified taste, charm, and a sense of style that was irresistible. Early in his career he recognized a burgeoning market in America with its increasing number of millionaires who desired the type of life that bespoke long family lines of wealth and titles, and the lifestyles they had seen in the country estates and grand city houses of Britain and the Continent. Duveen quickly became decorator, designer, architect, and purveyor of tasteful art, porcelain, furniture, rugs, and anything else that was required to set the table and stage for the highest standards of living by this aspiring class. Correspondence between Duveen’s staff in all three offices describes the kinds of frames, drapery, bric-a-brac, and paneling sold by the firm to set off a sculpture or painting being offered to Huntington or Frick as they built their homes.

But by 1964, Joseph Duveen had been dead for twenty-five years, and the cultural landscape had changed from his days of catering to and cajoling the rich. Warhol had captured the image of Jacqueline Kennedy’s stoic mourning in multicolored prints, the Beatles had conquered America. The styles that had once been defined by the firm were now largely retardataire.

Fowles (fig. 2), a loyal staff member for sixty years who had began his Duveen career as a the receptionist’s assistant in 1898, now owned the firm outright, but had not drawn a salary for more than two years as the firm had not turned a profit in some time. At 79, Fowles’ focus was on a retirement that would allow him to write his memoirs, but he wanted to close the firm to the best possible advantage to his small, loyal and longtime staff of fourteen, and provide them with pensions.

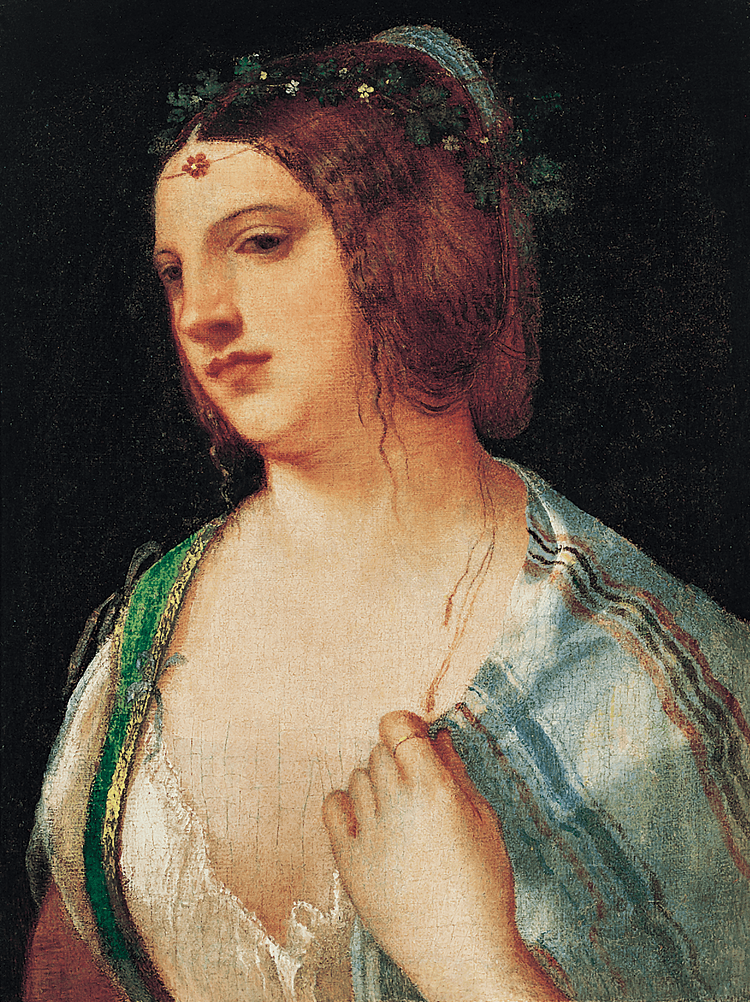

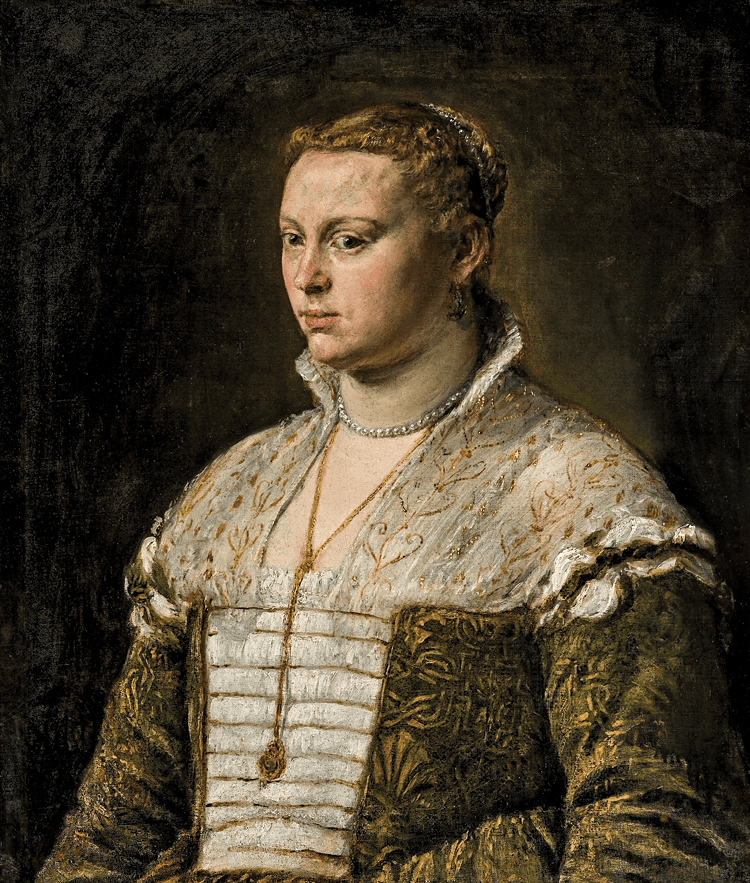

Between 1954 and 1964, Simon had purchased, through dealers and auctions, nearly 150 nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings, sculpture, and prints, including etchings by Rembrandt and Dürer. Several paintings created before 1700, including two by Rembrandt that had come from Duveen’s in 1956 (neither of which is still in the collection), were also part of Simon’s earliest purchases. Other early acquisitions, most of which are no longer in the collection, were works by Rubens, Lorenzo Monaco, Van der Heyden, Frans Hals, Giorgione, Gainsborough, and a painting attributed to Fragonard (now given to Alexis Grimou [1678–1733]). The small bust portrait of a woman attributed to Giorgione (Fig. 7) had originally been of interest when Simon saw it at Duveen’s in 1957, but he demurred, knowing the Giorgione attribution had been questioned and that the work had variously been ascribed to Titian, Cariani, and Mancini. Ultimately, the asking price of $190,000 put Simon off. By September 1963, the asking price was $192,500, to which Simon agreed, after first setting out labyrinthine terms of sale. This was just the beginning of a far more Byzantine agreement between Simon and Fowles a year later. A much larger deal was in the works.

On April 18, 1964, after much legal to-ing and fro-ing, Simon and Fowles came to an agreement, whereby the Norton Simon Foundation (one of two foundations set up by Simon in the 1950s) would purchase the entire stock of the Duveen Brothers Gallery, along with the building that housed it and its four-thousand-volume library. (The library would later be sold to the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts). Fowles kept control of the firm’s vast archives, which were later donated to The Metropolitan Museum of Art (now housed at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles), and he managed to negotiate a total payment of $4,000,000, which would support a pension program for most of the Duveen staff. Simon would employ Fowles and his wife, Jean, to stay on to advise during the transition, as well as to assist with the selling of parts of the stock that Simon had no interest in retaining, which was most of the furniture and decorative arts. The final agreement was signed in 1965. During the next few years, Simon recouped more than $1,800,000 of the initial expense through sale of some of the Duveen acquisitions through Sotheby’s auction house in Manhattan. The East 79th Street building was sold to the Acquavella Galleries for $425,000, for which two paintings were made in partial payment: a Renoir (later sold) and Henri Fantin-Latour’s White and Pink Mallows in a Vase. Institutions such as LACMA, the Princeton University Art Museum, The Metropolitan Museum, the De Young Museum in San Francisco, and others, benefited from extended loans, while Simon’s staff threw themselves into researching the extensive holdings.

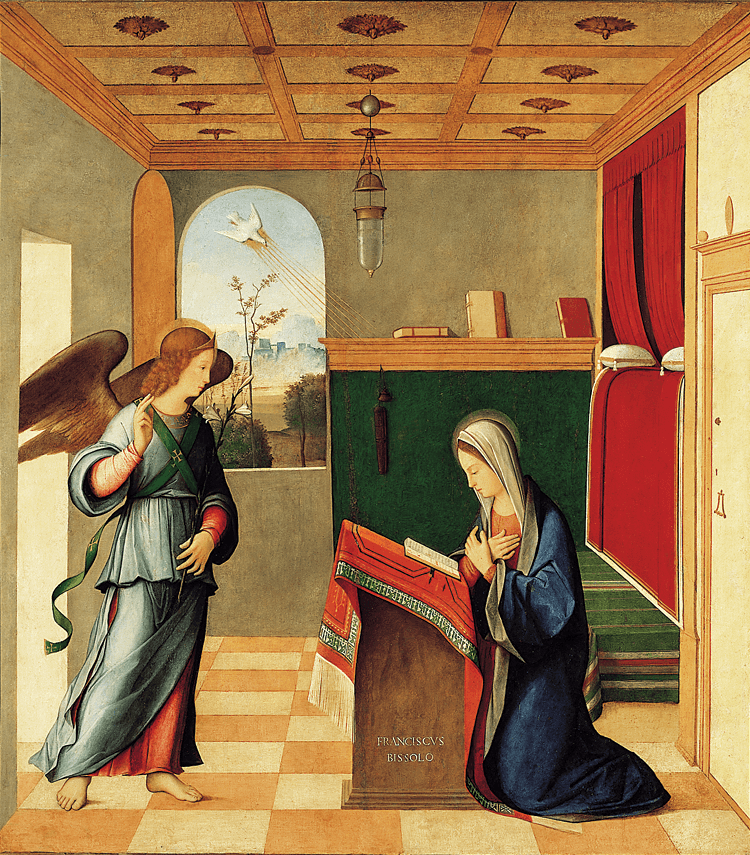

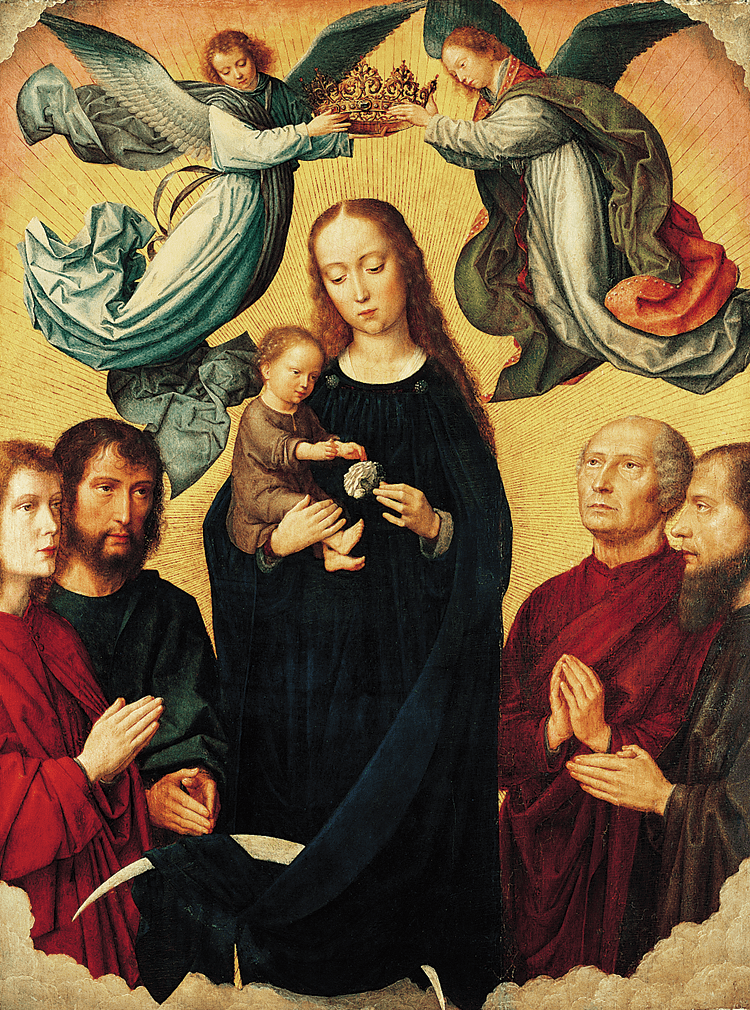

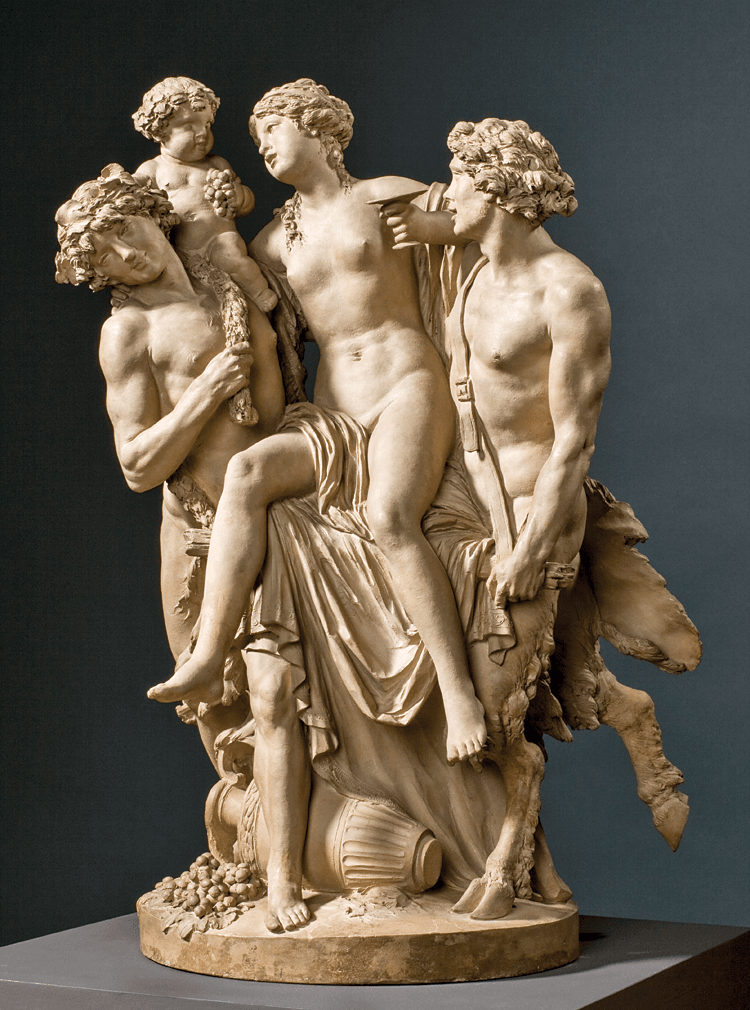

The Duveen works (around one hundred and thirty) that Simon retained are the focus of Lock, Stock and Barrel: Norton Simon’s Purchase of Duveen Brothers Gallery at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California. The exhibition serves to emphasize Simon’s business-style approach to assembling a remarkable collection for his museum, but also how his purchase emboldened his interest in Old Masters. Included in the exhibition are about twenty works that are generally on display in the museum’s permanent galleries, such as Francesco Bissolo’s Annunciation (Fig. 8) from around 1500, Gerard David’s Coronation of the Virgin (Fig. 9), Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of Antoine Paris from 1724, and Clodion’s elegant terracotta of Bacchante Supported by Bacchus and a Fawn dated 1795 (Fig. 10).

Paintings, sculpture, and other objects from the museum’s vault, some of which have not been on view since their purchase, round out the assemblage. They include a haunting Portrait of a Lady (Fig. 11), from circa 1570, attributed variously to Jacopo and Leandro Bassano; it was previously in the Edward Cheney collections of Venice and Badger Hall in Shropshire, England. Its frame was made by Ferruccio Vannoni, a Florentine artist and carver employed by the Duveen Paris office in the 1930s to create appropriate period frames for their stock, a number of which still encase the Duveen paintings in the collection. Also on display are the few pieces of British art that Simon retained, including a stunning portrait of Lady Hamilton as “Medea,” from 1786 by George Romney (Fig. 12). The painting was one of several portraits by Romney, including two others of Emma Hamilton, in the Duveen stock; on the advice of several scholars, Simon sold all but this one. With the renowned Duveen-inspired British art collection at the Huntington Museum in San Marino, Simon felt it was unnecessary to retain most of the works by English artists included in the Duveen purchase.

In a New York Times article dated April 21, 1964, Edward Fowles recounted a version of the conversation that led to Norton Simon purchasing the Duveen Brothers Gallery: “[A]bout four or five months ago, Mr. Simon told me he wanted to buy a lot of stuff. I told him . . . this would mean that much of my finest stock would be gone. He said ‘Why don’t I buy the whole thing, lock, stock, and barrel, including the building.’ That’s how it started.”

Lock, Stock and Barrel: Norton Simon’s Purchase of Duveen Brothers Gallery, which runs at the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, Calif., until April 27, 2015, includes an overview of the legendary “Duveen frames” by Curator Gloria Williams Sander, and detailed descriptions of technical issues by Conservator John Griswold.

An accompanying book by Simon’s curator of forty years, Sara Campbell, tells the story of Simon’s acquisition of the renowned Duveen firm. For more information visit www.nortonsimon.org.

Carol Togneri organized Lock, Stock and Barrel: Norton Simon’s Purchase of Duveen Brothers Gallery at the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, Calif., where she is chief curator.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.