A Passion for Art and Life

-

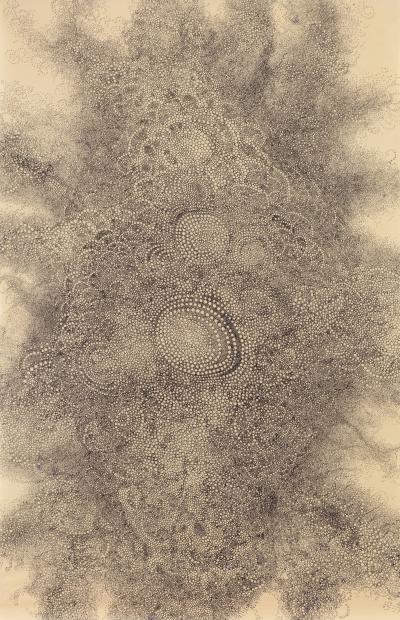

Peter Forakis (b. 1927), Lazar Lightning, 1967. Forakis was one of a group of young painters and sculptors, mostly from California, who joined Dean Fleming and Ed Ruda in a communal art space at 79 Park Place in New York City during the early 1960s. The cooperative Park Place Gallery opened officially in 1963 but moved to West Broadway (as the Park Place Gallery of Art Research) in 1965 with new financial support from a group of collectors, which included Betty Blake and her husband, Allen Guiberson.

-

English in inspiration, Indian Spring is a uniquely American blend of Georgian principles and neocolonial detailing. It represents a nascent vernacular style which emerged in the United States during the 1920s. The arrival of the Great Depression seemed to quash the development of this particular line of architectural design.

Betty Blake pushes back a stray tendril of white hair, shoos her overly-eager dog Reno away from her visitor’s feet, and with a laugh says, “I just flew in from Dallas at one a.m. so I’m not quite together, but I’m so happy you’re here.” Betty has just returned to Newport, Rhode Island, for the season, a pilgrimage she has repeated almost every summer for the last ninety-one years.

Fresh-faced and chatty after only a few hours of sleep, already she’s talking about her next adventure: she’s leaving in one week to attend Art Basel in Switzerland. “I want to see everything that’s going on…I’m very, very interested in what they’re painting today.” Long-time friend Roderick O’Hanley, on the board of trustees for the Newport Art Museum, says, “We should all learn a lesson from Betty on how to live life. She’s always on the go, always interested in something new.”

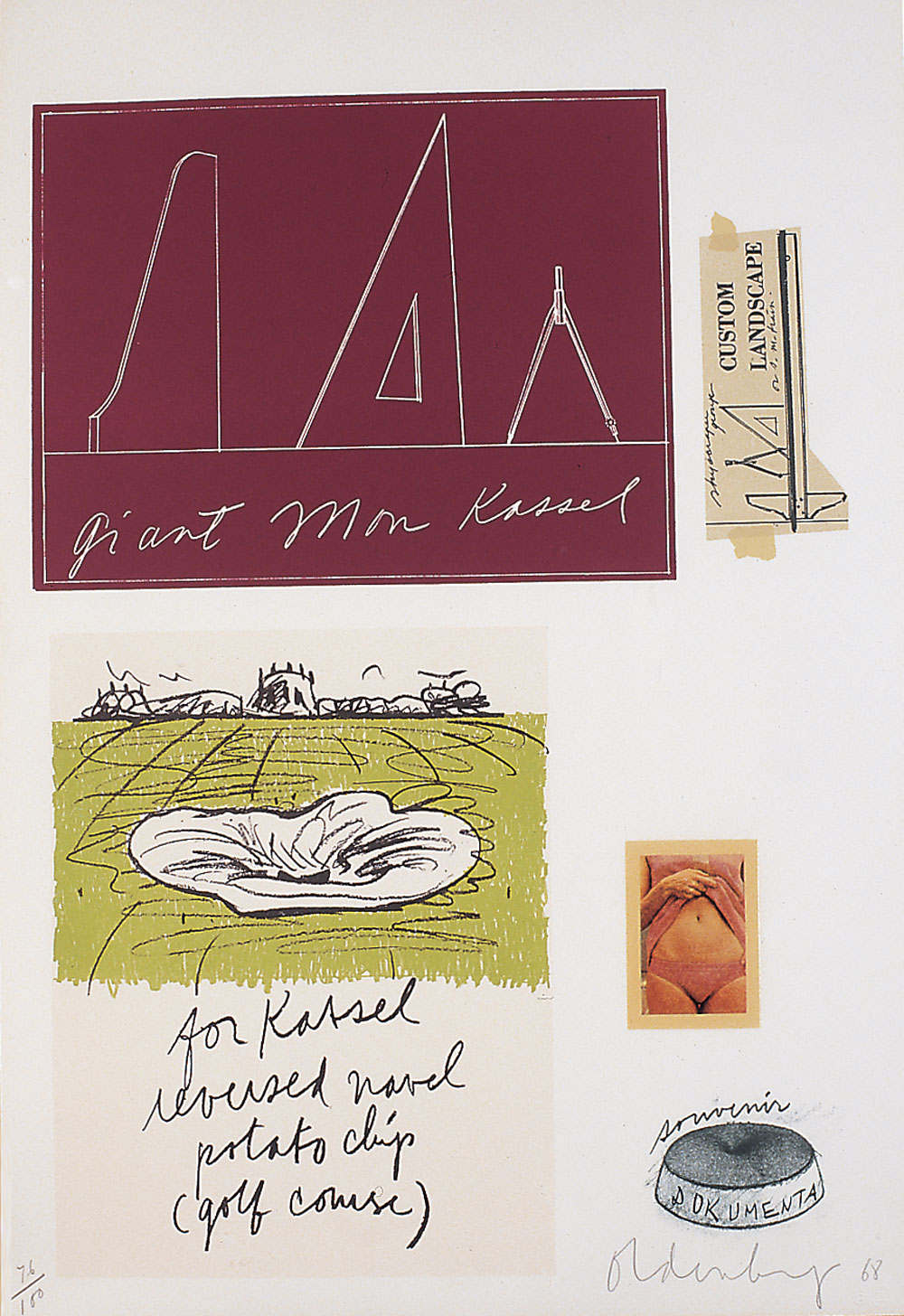

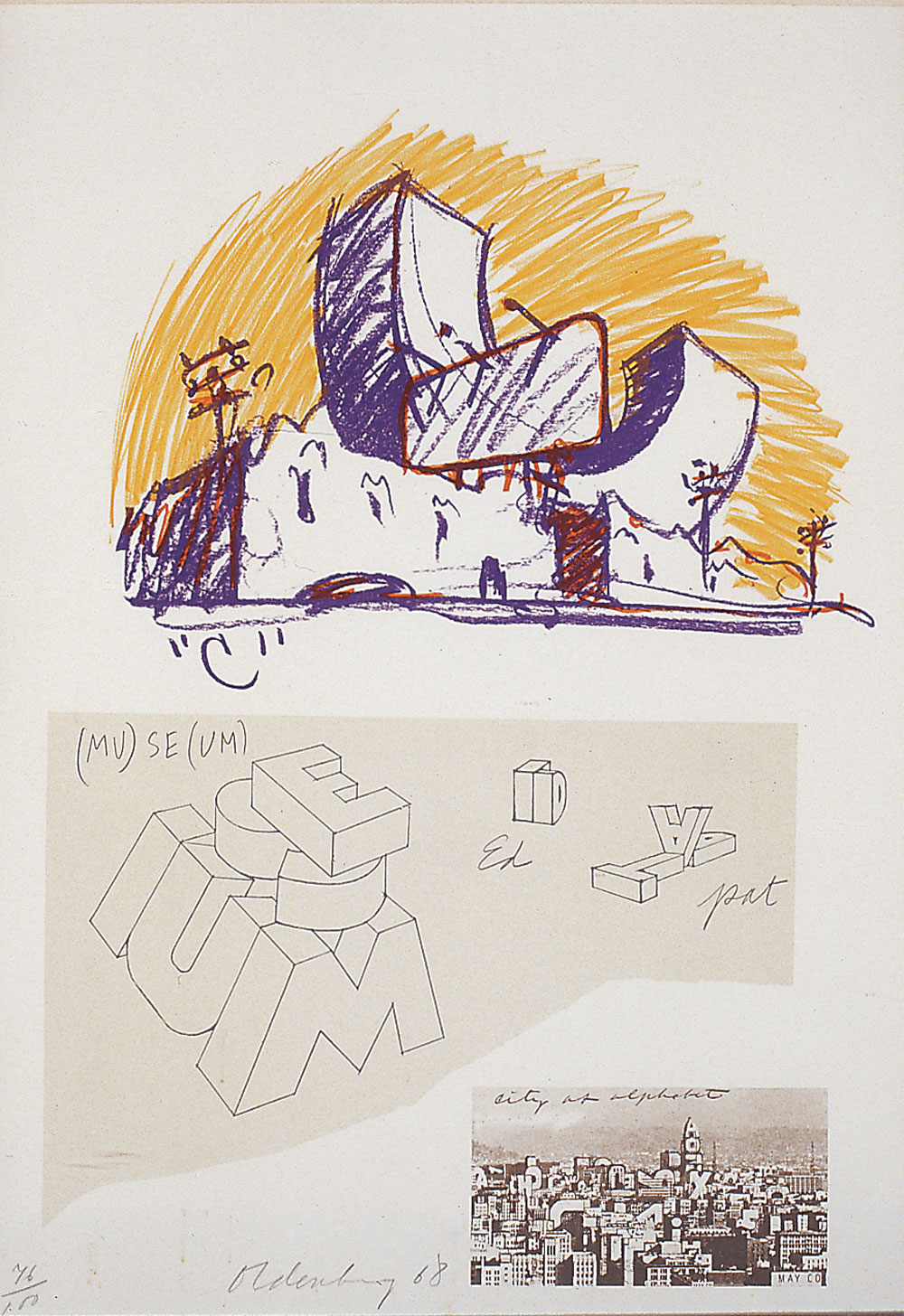

Betty’s restless intellect has kept her at the forefront of contemporary art for the last six decades as she’s amassed an important collection of works by post-World War II artists including luminaries Alexander Calder, Jim Dine, Alberto Giacometti, Alfred Jensen, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Joan Miro, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, George Segal, Frank Stella, and others.

-

Flanking a large Lee Bontecou (b. 1931) charcoal on canvas drawing on the far wall are works by (L–R) the Hungarian-French father of Op Art—Victor Vasarely (1908–1997), Edward Movitz; Alexander Calder (1898–1976), and Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997). Betty used a Picasso (1881–1973) vase to make the table lamp to the right of the sofa. She and legendary English decorator, Syrie Maugham (1879–1955) were good friends. Maugham designed the brilliantly colored tufted armchairs in Betty’s living room.

-

The functionalism and geometric styling of two leather and stainless steel chairs complement three Alfred Jensen (1903–1981) screen prints over the sofa. Frank Stella’s (b. 1936) colorful silkscreen Shards I, hanging beside the terrace doors, was printed in 1982—more than two decades after his hard edge black stripe paintings shook up the art world at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Stella was one of the first major young artists to break with abstract expressionism. A bronze sculpture by Howard Newman (b. 1943) shares the coffee table with a steam machine model built by Betty’s fifth husband, Allen Guiberson.

-

Two 1969 lithographs from Robert Rauschenberg’s (b. 1925) Stoned Moon series flank the fireplace: Marsh (left) and Loop (right). Above the mantel hangs a painting by abstract-surrealist Charles Howard (1899–1978). The Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964) sculpture, second from the left on the mantel, combines elements of figuration and abstraction.

Betty is a former president and chairman of the board of the American Federation of Arts, a former board member of the Dallas Museum of Art, the Newport Art Museum, Dallas Theater Center and TACA, Inc., advisory council member of the College of Fine Arts, University of Texas, and former president and board member of the Dallas Museum of Contemporary Art (DMCA). “Betty was in the forefront of supporting and collecting these artists and their work,” notes Karl E. Willers, the Newport Art Museum’s Executive Director. The exhibition The Collection of Elizabeth Brooke Blake, running at the Newport Art Museum through October 7, 2007, describes Betty as “an incomparable enthusiast and strenuous advocate of modern and contemporary art, and collecting art has been one of the great passions of her life.”

Betty has been a Newport summer resident most of her life. As a girl, she summered at Cave Cliff (now owned by Salve Regina University), and she spent two decades at Seafair as a young wife and mother with her fourth husband, Tom Blake. After their divorce in the 1960s, Betty bought Indian Spring, the 5,700-square-foot house designed by Frederick Rhinelander King in 1927 for his brother, Leroy King. From the bedrooms upstairs at Indian Spring, the tall chimneys and peaked roofs of Seafair, her former home, are visible through the morning mist. “I loved that house…but to run it was very difficult. We lived there and we had a lot of children and it was fun. But I used to look up at this house and think, “Oh, I wish I had that little house and I didn’t have to worry about all this.”

-

From France, 1960, a sculpture by Marisol (Marisol Escobar) shelters under a faux canopy in the entry hall, painted in 1982 by Leonard Fruhman, a good friend of Betty’s. Fruhmen inscribed the mural with the words, “For Betty, a labor of love.” Marisol was born in 1930 in Paris to Venezuelan parents. She studied with abstract expressionist Hans Hoffman, and during the 1950s, joined the circle of leading abstract expressionist painters in New York. Exposure to pre-Columbian artifacts influenced her move from painting to sculpture.

-

Betty grew up surrounded by pre-twentieth century art. The nineteenth-century American marine painting is from her parent’s house in Philadelphia. The welded brass sculpture was created by American James Metcalf (b. 1925) in 1959. During the 1950s and 60s, Metcalf was recognized as one of the most promising artists of his generation. Kenneth Price’s Blue Stem, a small-scale ceramic piece, sits on the marble-top table.

-

Alexander Calder’s (1898–1976) gouache Crabs (date unknown) hangs above the mantel in the library. The angular, red toned #19 Cup, by Kenneth Price (b. 1935) is emblematic of the 1970s reaction against the large-scale works of the 1950s and 1960s. Price has been an important figure in the resurgence of ceramics in fine art.

-

In the dining room, fuchsia walls set off the aqueous blues and greens of Stanley William Hayter’s (1901–1988) large oil painting, Slipstream, 1962 (right). Active in France and the U.S.A. during his lifetime, Hayter’s work and his writings on automatism influenced Jackson Pollock and others in the emerging New York school of abstract expressionism.

-

In My Cincinnati Studio, 1963, is one of the finest works by Jim Dine (b. 1935) left in private hands, according to Newport Art Museum executive director Karl Willers. Betty purchased the large oil on canvas (72 x 96 inches) in 1964 from the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York City.

-

This Provincetown, Massachusetts, scene was painted by Houghton Cranford Smith (1887–1983).

Betty’s love of color is evident everywhere—in the art, but also in the décor. Moving from room to room is like taking a tour of Josef Albers’ palette. Walls are splashed with bold, intense colors and much of the furniture is similarly unabashed. Shelves, tables, and walls are crowded with artworks. Although her homes in Dallas and Newport are distinctly different in style, Betty does not buy art with a particular location in mind. “I only buy what I love and I always find a place to put it.”

The works of art in Betty’s Newport house were collected over a period of many years and she is still “looking constantly,” having made several recent purchases. Independent and firm-minded, she has never worked with an advisor, although she often discusses art with friends. When asked if any family members have influenced her choices she answers “No!” with a laugh.

|

Raised in a world of privilege and schooled in Paris in the 1930s, Betty was always surrounded by fine art. She wandered the galleries of the Louvre every week as a student, admiring works by the great sixteenth- and seventeenth-century painters. Betty remembers thinking, “If these historic paintings are so staggeringly beautiful, what are they doing today?” From there, she began exploring the world of modern art.

It would be another decade before Betty started seriously collecting. Moving to Dallas in 1943 with her third husband, Jock MacLean, she began collecting works by Mexican and Texas artists, traveling regularly to Mexico City to buy art from a gallery called Inés Amor. She recalls, “[It had]…all the great Mexicans—Diego Rivera, José Orozco, David Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo.”

In 1950, she opened the Betty MacLean Gallery in Dallas as a showcase for contemporary art, the first of its kind in Texas. Painter Donald Vogel (1917–2004) served as gallery director. Betty admits it was often a challenge to win over clients who walked in looking for landscapes and Texas Bluebonnets. For their first show, the pair worked with the Knoedler Gallery in New York to bring in works by Chagall, Picasso, Winslow Homer, Cassatt, Renoir, Matisse, and other modern masters. In his 2001 book Memories and Images: The World of Donald Vogel and Valley House Gallery, Vogel recalled that $6,000 would have picked up a large Monet. “It all seems ridiculous now,” he wrote. “We failed to sell any of them; people complained that the prices were unreasonable.” Reflecting on the experience, Betty says “I worked like a dog but I still didn’t sell much. There was a Picasso for only a few thousand dollars—a seated nude. People in Dallas then would rather buy Cadillacs!”

Over the years, Betty has played an important role as an arts advocate in Texas, which now boasts some of the finest cultural institutions in the country. She also supported and promoted the work of many now-prominent American artists. She was part of a group of collectors who stood behind the sculptors and painters of the Park Place Gallery in New York City and she is or was on a first-name basis with people like Robert Rauschenberg, David Bates, Richard Lindner, and gallery owner/artist Betty Parsons, to name just a few; all of whom are represented in her collection.

Betty advises beginning collectors to, “Look, look, look and buy what you like.” She acknowledges, “You may make some mistakes but there’s only one way to buy—if you love it. Bring it home and if you don’t like it, take it down and put it in the closet.”

|

|

|

-

Contemporary works line the stairwell and upstairs hall. The foreground is dominated by Alan Davie’s Reach for Joy (1960) on the left and a large abstract painting by Larry Zox (b. 1936) on the right. Born in Scotland in 1920, Davie’s work was influenced by Zen Buddhism and jazz music. Much of his work from this period is filled with symbols derived from American Indian pottery, maps, and ancient rock-carvings. A work by Alexander Calder (1898–1976) is visible at the end of the hall.

|

|

|

|

-

Josef Albers (German-American, 1888–1976), Influence, 1964. Oil on masonite, 40 x 40 inches. Acquired at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, D.C. (1965). Influence was part of Albers’ Homage to the Square series through which he explored the interplay of colors and the “exciting discrepancy between physical fact and psychic effect of color.” Although he was famous for his disciplined technique, Albers used colors as metaphors for human relationships and did not want his works to be seen as strict geometric interpretations.

At 91, Betty is still passionately engaged with the world of art. Rod O’Hanley recalls a recent conversation. “She called me to say, ‘Well, I’ve done it! I’ve done it again!’ ‘What did you do?’ I asked. She’d bought a huge picture from a gallery. She’d been following the artist—tracking his progress and finally found the perfect piece. But then she said, ‘Now for heaven’s sake don’t tell the children.’”