In Search of New Horizons: Surfing the Records of American Folk Art Gallery

|

As a result of the pandemic, instead of a much-anticipated walking trip in Japan last spring I found myself on a glorious journey of discovery exploring the records of the American Folk Art Gallery, an epicenter of New York City’s early twentieth-century art scene.1 Not only did I find new material to consider, but the experience has also given me a much greater understanding of how folk art came to be considered emblematic of our national spirit and why so many of the artists carried by this gallery are represented in our public institutions.

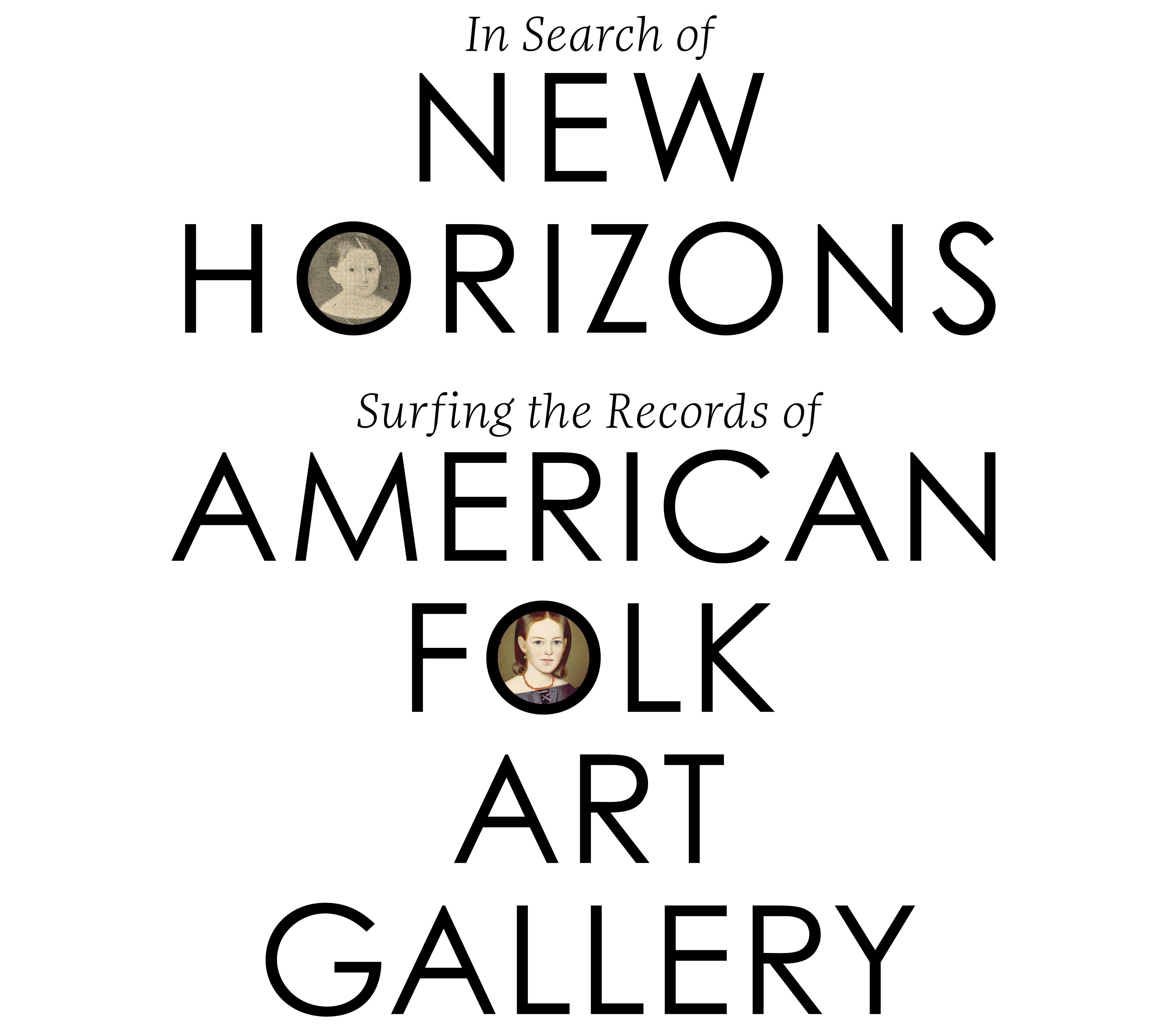

The first metropolitan gallery in the country to make a business of marketing folk art, from the outset, the gallery promoted folk art as deserving of critical attention for its formal qualities. Begun as a joint venture between gallery owner Edith Gregor Halpert (born Russia, 1900–1970) and folk art scholar Holger Cahill (born Iceland, 1887–1960), when the gallery first opened in 1931, it occupied the second floor of Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village, Manhattan (Fig. 1).

|

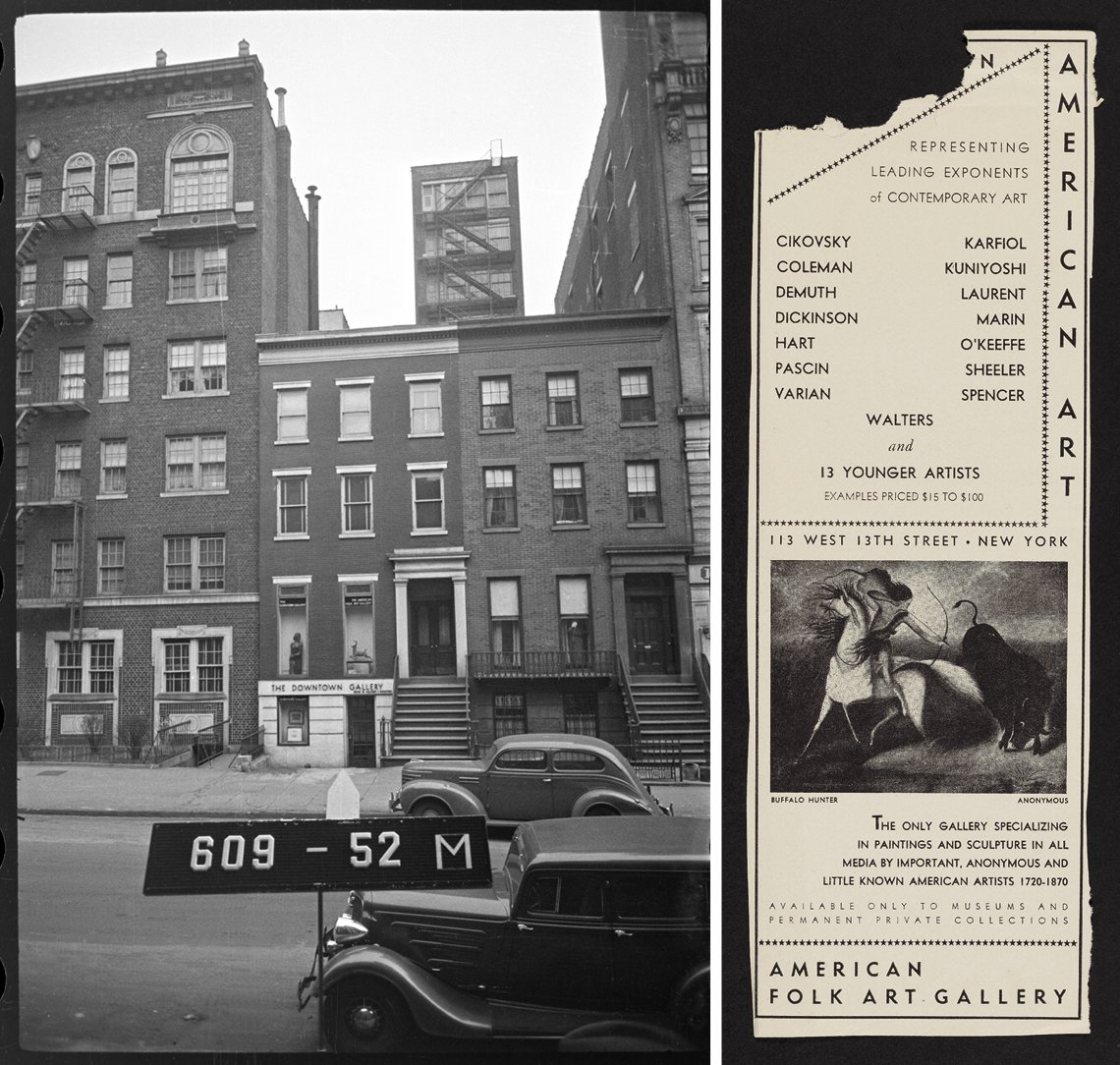

Fig. 1, left: Downtown Gallery, 113 West 13th Street, NYC, ca. 1939. Note the sculpture on display in the windows on the second floor. Courtesy Municipal Archives, City of New York; image identified as “Block 609 lot 52 ‘Downtown Gallery.’” Fig. 2, right: American Folk Art Gallery advertisement, not dated. Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5642, frame 1008. Carefully chosen paintings like the one in this gallery advertisement underscored the idea that folk art was an authentic expression of the spirit of the country. |

|

Fig. 2a: Unknown artist, Buffalo Hunter, 1844. Oil on canvas, 40 x 51¼ inches. Santa Barbara Museum of Art; Gift of Harriet Cowles Hammett Graham in memory of Buell Hammett (1945.1). |

Halpert and Cahill first met in Ogunquit, Maine, in the 1920s, where they observed visiting artists using folk art to furnish the fish shanties they were occupying. An alliance between the two seemed promising. Halpert wanted to expand the market for contemporary art, and Cahill, an early proponent of the dynamic relationship between folk art and contemporary art, provided Halpert with the ideology and the contacts to make it possible. Combining the two kinds of inventory on the same premises was so successful that folk art remained an integral part of Halpert’s business until its closure in 1973 (Figs. 2, 2a).

Instead of emphasizing the historical associations or utilitarian value of folk art as was customary, the gallery presented folk art as American art from an earlier time. Their first exhibit, American Ancestors, in 1931 included work in a variety of media. The title was not a reference to ancestral portraits, but to ancestors of American contemporary art. The gallery marketed all genres, provided the work had sufficient aesthetic appeal (Figs. 3, 3a) (Figs. 4, 4a).

|

Fig. 3a: Attributed to Orlando Hand Bears (1811–1851), Miss Tweedy of Brooklyn, ca. 1845. Oil on canvas, 41 x 33 inches. Detroit Institute of Arts; USA. Gift of Mrs. Edith Gregor Halpert/Bridgeman Images (53.107). |

|

Fig. 3, top left: Masterpieces in American Folk Art, Exhibition Feb. 25–March 22, 1941. First floor, the Downtown Gallery, 43 East 51st Street, NYC. Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5654, frame 663. Fig. 4, right: Museum Collection, American Folk Sculpture. Exhibition, May 14–June 1950, the Downtown Gallery, 32 East, 51st Street, NYC [third location]. Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5654, frame 676, Reel 5640, 857–863. Fig. 4a, bottom left: Unknown maker, Locomotive weathervane, 1840–1860. Sheet zinc, brass, iron, and paint. 54 x 42 x 3 inches. Collections of Shelburne Museum; museum purchase (1950), acquired from Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery (1961-1.130). Photography by Andy Duback. This weathervane, purchased by Halpert from the Isabel Carleton Wilde collection had a history of being discovered in Rhode Island (Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5563, frame 764–766.) It was sold to Electra Havemeyer Webb, founder of the Shelburne Museum. |

| |

Fig. 5: Samuel Jordan (1804–?), Eaton Family Memorial, 1831. Oil on canvas, 21 ⅞ x 15½ inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (1955.11.9); Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. |

Halpert and her business records were already of interest to me, having written about a painting by Samuel Jordan bearing one of her gallery labels.2 (Figs. 5, 5a). After seeing Rebecca Shaykin’s landmark 2019 exhibition Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art (the Jewish Museum, NYC) and reading her book Edith Halpert: The Downtown Gallery and the Rise of American Art (Yale University Press, 2019), I was inspired to visit this archive once again; what a treasure trove it has proved to be.

For those of us who covet folk art, or “art in the primitive tradition,” as Halpert once termed it, the files stored in three-ring binders and referred to as notebooks, and the business records kept by the American Folk Art Gallery are especially interesting as they provide a first-hand glimpse into the folk art market in this country in its formative years.

As revealed there, the gallery purchased work from up and down the eastern seaboard and as far west as California through auction houses, dealers, “runners” (aka scouts), executors of estates, and sometimes directly from family members. Folk art collectors falling on hard times, such as Juliana Force, Isabel Carleton Wilde, and Elie and Viola Nadelman also added to the gallery’s holdings. In the summer of 1931, Halpert drove through New England and Pennsylvania searching out inventory. While in Vermont she claimed to have enlisted the local fire brigade to remove an unusual deer weathervane from a barn.3 Meanwhile, Cahill ventured as far south as Florida and Tennessee to acquire choice merchandise.

|

Fig. 5a: Downtown Folk Art Gallery label for Fig. 5. National Gallery of Art; image courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum. |

To build interest in their stock, the gallery regularly lent inventory to exhibitions, such as the much-lauded American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900, which Cahill curated in 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC. The gallery also shipped inventory to regional and university museums across the country in the hopes it would be either added to their respective collections or secure sales from private collectors. The list of venues is quite staggering, from Wellesley College in Massachusetts to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in California, to name just a few.

Writing, lecturing, and preparing exhibitions, all of which Cahill and Halpert did, helped drive the market for folk art. In 1947, Buffalo Hunter (fig. 2a) was included in a traveling exhibit showcasing American paintings at the Tate Gallery in London, where it was praised for having no contemporary counterpart in England.

The gallery’s policy of limiting their patronage to museums and private permanent collections (later known as discriminating collectors) was particularly effective. One of Halpert’s first clients was Abby Aldrich, wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who filled her many homes and two museums with purchases from Halpert’s galleries. The online records identify what Abby bought, where it was exhibited, and what she gave to various public institutions.

Halpert was a first-class record keeper, the result, no doubt, of her formative years spent working in her mother’s candy store and in various retail and investment firms in New York City. Aside from having a keen eye for quality, she was an especially astute businesswoman, buying into a market that was still grossly undervalued. She offered payment plans and rentals, collected commissions for finding inventory for the gallery, and brokered sales to public institutions. For expensive items such as works by Edward Hicks (1780–1849), she proved how resourceful she could be by offering auction houses and galleries a shared interest in what she purchased. She also could be generous to the institutions that supported the gallery. Halpert acquired Miss Tweedy of Brooklyn (fig. 3a) in 1940, exhibited it in her gallery in 1941, then gave it as a gift to the Detroit Institute of Arts.4

|

Fig. 6: “Portraits of the Eddy Twins by Joseph Stock,” The Springfield Sunday Union and Republican, Springfield, Mass., January 3, 1932, page 6E. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5642, frame 1029. |

| |

Fig. 7: American Character Beauty. Clipping from New Yorker September 1941 featuring one of the any portraits by William M. Prior acquired by the gallery. Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5558, frame 882-883. Purchased: Cambridge, Massachusetts 11/39 EGH NYC. Sold: Edson 4/12/41. “Used as advertisement in ‘class’ magazines by Shulton, Inc. / with whom Miss Edson is associated. This advertisement appeared in the NEW YORKER, Sept. 1941 (from which this was clipped).” |

Halpert placed inventory in department stores such as the Gimbel Galleries in Philadelphia, Marshall Fields in Chicago, and Neiman Marcus in Dallas; invested in good quality images to accompany her carefully worded press releases; and in the archive there are clippings of magazine advertisements featuring folk art portraits being used to market household products like face powder and custard.5 All of this effort was to garner better coverage, build interest, and associate folk art with contemporary living (Figs. 6, 7).

Profits from Halpert’s folk art gallery were substantial enough to underwrite the expenses incurred in supporting living artists whose work was being exhibited at the Downtown Gallery. After her partnership with Cahill was dissolved in 1940 and she moved further uptown to 43 East 51st Street, Halpert placed her folk art on the first floor instead of the second and continued to collect and feature folk art until her death in 1970 (Fig. 8).

For those with an interest in folk art portraits, the catalogue sheets found in Notebooks (section 3.1) are particularly informative. Each sheet has a photograph of the portrait, notations concerning dimensions, medium, details about the sitter if known, when, where and from whom the portrait was acquired, details concerning family history/provenance, transcriptions of any inscriptions or labels, as well as exhibition and publication history (see fig. 12). Some entries record restoration work done and include photographs of before and after treatment. Excerpts of exhibition catalogue entries are also sometimes included along with gallery correspondence and the occasional auction catalogue illustrating the portrait in question. As these were working gallery records, annotations such as buyers’ names were included right up until the time the gallery closed in 1973.

In the earliest records, prolific artist Ammi Phillips was catalogued as unknown or anonymous. Other artists were tagged by geographical location such as the Fall River artist. Occasionally, as in the case of Joseph Stock, a full biography of an artist is included. Fortunately, portraits by some of our best known artists today such as John Brewster or Erastus Salisbury Field are easily recognizable from the black and white photographs despite their varying sizes and condition.

The notebooks also feature unique signed and dated works, such as an 1831 fireboard by decorative artist Jonathan Poor, acquired from the Isabel Carleton Wilde collection of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a watercolor by Elizabeth Andrews of Long Island, which could easily have been mistaken for a Eunice Pinney composition.6

|

Fig. 9, left: Girl in Rose Garden, possibly by Joshua Johnson (1763–1832). Gallery catalogue sheet, Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5558, frame 510. Fig. 10, right: Joshua Johnson (1763–1832, In the Garden, ca. 1805. Oil on canvas, 27½ x 19¾ inches. Baltimore Museum of Art, Md (1967.76.1); Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. |

In some cases, the notebook entries may provide key details of provenance concerning a particular work of art as well as alert one to other works by an artist that have escaped critical notice. For Joshua Johnson (1765–1865), the first professional Black artist to work in the United States, there is a catalogue sheet for his Portrait of Emma van Name, circa 1805 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016.116).7 Subsequent catalog sheets of a brother and sister, both set in a rose garden with butterflies, similar to Johnson’s In the Garden, that suggests they, too, are probably by his hand (Figs. 9, 10). Halpert is listed as having acquired them from a distinguished private collection in NY before selling the pair to the gallery, a good example of how discreet she could be when it came to protecting her sources.8

Other entries provide intriguing, but ultimately unfounded, leads to authorship such as Girl in Garden, described as “signed lower right Athony [sic] Drexel, 1828.” The painting had been purchased at a Parke-Bernet auction in New York City on Feb. 18, 1938, and sold to JDR [Abby Aldrich, wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr.] the next day (Figs. 11, 12). In 1955, during conservation it was discovered that the inscription was a later addition; it was then removed. This artist has yet to be identified.

|

Fig. 11, left: Artist unknown, Girl in Garden, ca. 1840. Oil on canvas, 39⅞ x 27¼ inches. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (39.100.2). Fig. 12, right: Gallery catalogue sheet, Girl in Garden, ca. 1828. Downtown Gallery records 1824–1974, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Reel 5558, frame 344. |

Details of the gallery’s inventory are especially edifying as so much of it is now in our public institutions, where it is considered an integral component of our cultural heritage. This had been the gallery’s goal from the outset and the records donated to the Archives of American Art reveal how this came about.9 Such was the quality of the gallery’s stock that when works by artists they once carried, such as Edward Hicks, Joseph H. Davis, and William Schimmel, do appear on the marketplace, they command some of the steepest prices. What a remarkable legacy for the first folk art gallery established in this country by two immigrants in the midst of the Great Depression.

1. Thanks to funding provided by the Henry Luce Foundation, the gallery records can be accessed on the website of the Archives of American Art, at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/downtown-gallery-records-6293.

2. Deborah M. Child, “Samuel Jordan: Artist, Thief, Villain,” Antiques & Fine Art magazine, Summer/Autumn 2009 issue (vol. IX, issue 5) 146–153.

3. Lindsay Pollock, The Girl with the Gallery and the Making of the Modern Art Market (Location? Public Affairs, 2007), 135–136.

4. Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5558, frame 504, 868-869.

5. For more information on Early American Old Spice products including their face powder see https://www.cosmeticsandskin.com/companies/shulton.php. Another advertisement found in the gallery files featured Milton W. Hopkin’s portrait of Agnes Frazee and Child (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch) promoting General Food’s egg custard. Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5559, frame 102.

6. Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5559, frame 855-857 & frame 1083-1085. Purchase slip dated Oct. 17, 1947 Mr. Bradford Kelleher paid $55 for watercolor Schooldays by Elizabeth Andrews dated 1826 found in Long Island. Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5615, frame 691.

7. The gallery records note: “According to the previous owner, the Van Name family was among the early settlers of Staten Island where the painting was found. Sold to Garbisch in 1959.” Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Reel 5558, frame 313, 314, 315.

8. For details of this portrait #1010a and that of her brother Boy in Rose Garden #1010b see Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5558, frames 327–331, 510–512. The sales slip, dated January 7, 1947, lists Halpert as the seller (inventory number 315) to the gallery, for $189. These were shown in a gallery exhibit of American Folk Art in 1949. Sold to Edgar William Garbisch in 1956, their current location is unknown. Downtown Gallery Records Reel 5558, frame 327–328, 510–512.

9. In an exhibit of folk art held at her premises on 32 East 51st St., Halpert specified “Exhibits not for sale except to museums.” Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974, bulk 1926–1969. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 5640, frame 807.

Deborah M. Child is an independent scholar and lecturer with a particular interest in folk art of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Samples of her publications can be viewed at www.deborahmchild.com. The author would like to thank Marisa Bourgoin, Head of References Services, Archives of American Art, for her assistance throughout the preparation of this article.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|