Rapid Jottings: Milton Avery's Search for Vitality

In order to paint one has to go by the way one does not know. Art is like turning corners:

one never knows what is around the corner until one has made the turn.

— Milton Avery, as quoted in Burt Chernow, Milton Avery Drawings, 1973

On Avery & Modernism

What is it that makes Milton Avery’s (1885–1965) art appear so much more “modern” when compared to canvases by his contemporaries, whether they be figurative or abstract artists? With modernism, the search for immediacy, for quickness, for vitality—the pursuit of effects intrinsic to the sketch became the ends rather than the means of artistic achievement. No longer relegated to a stage within the production of a finished work of art, characteristics of drawings and studies became increasingly appreciated for their ability to convey a world of change, speed, and novelty synonymous with all that was “modern” in people’s lives and daily experiences.

Avery’s practice takes this modernist transformation in taste to a level that is neither as prevalent in any predecessor nor as refined in any successor. It is for this reason that Avery and his art are described as being at the end of modernism. Ironically, it is Avery’s rather conventional working process—his conservative method of preparing for works on a canvas by making a series of drawings and studies on paper—that allows this description. Avery’s genius can be seen in the way that he looked discerningly at the effects he was able to achieve in his rapid jottings and spontaneous scribbles. He meticulously works out ways to translate the notations and outlines captured in his works on paper into his oils on canvas.

It is difficult to classify Avery’s art in the usual genres. While his works duly fall under the categories of landscapes, seascapes, figures, portraits, self-portraits, and still lifes, Avery’s oeuvre includes, a number of categorical combinations such as the figure in the landscape, that can also be identified as a portrait, that render the categories themselves meaningless (Fig. 1). What is important in Avery’s subjects is that they are derived from his personal observation of the natural world and his experience of the simple realities of domestic life among family and friends.

On Avery’s Life

Milton Avery, the son of Russell Eugene and Esther March Avery, was born in Altmar, New York, a small town near Oswego, on March 7, 1885. When Avery was eight years old, his family moved to Hartford, Connecticut, his home for the next twenty-four years. Upon graduating from high school he took a low-paying job at a local typewriter factory, but in hopes of finding more lucrative employment as a commercial artist he applied for a course in lettering at the Connecticut League of Art Students in Hartford. Unable to gain admittance to the over-crowded lettering class, he opted for a drawing course at the League taught by Charles Noel Flagg and Albertus Jones. This single semester of drawing in charcoal was Avery’s only formal art training in a painting career that would span more than fifty years.

In 1924, he met Sally Michel, an illustrator for the New York Times. He moved to New York in 1925 and married Sally, who financially supported the family for the next 25 years. In the fall of 1949, Avery had a heart attack. Sally was told that her husband would live for only a year at best. Although he would create some of his best work over the next decade and would live for more than fifteen years, Sally recalled that Avery never regained his earlier health after this first heart attack. Avery’s health began to deteriorate rapidly in the early 1960s. After an extended period of hospitalization, Avery died on January 3, 1965, at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. A memorial service attended by over 600 artists and friends was held in his honor at the Ethical Cultural Society in New York City.

On Avery’s Style

Avery’s career shows a process of consistent development and refinement, intimately connected to his creative method and reflective of his personal life. However, Avery’s earliest works of the 1920s and early 1930s possess few similarities to his mature work of the 1940s and 1950s (Fig. 2).

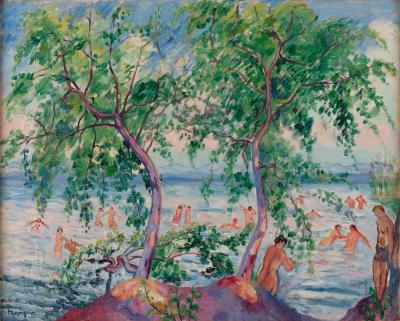

Avery worked almost exclusively with subjects derived from personal experience. The observations that provided Avery with his subjects influenced his use of color and form as well as the development of his individual style (Fig. 3). This choice of subject, rather than adherence to artistic movements and aesthetic ideologies, had a paramount influence on Avery’s formal means.

The large, flat color areas that Avery renders reveal a modernist concern for asserting the flatness of the painting’s canvas support. The reduction of all areas of the canvas to simple color shapes—regardless of whether they refer to figures, objects, or settings—results in the assignment of equal aesthetic value, and similar visual weight to all areas of the painting surface. Throughout his life, Avery was a painter concerned with meticulously refining his palette and carefully balancing his compositions.

On the Use of Color

With the elimination of unnecessary illusionistic detail and simplification of forms into a few flat shapes, color naturally became a dominant element with Avery’s art. Avery has always been recognized as a colorist of the highest quality and most inventive means.

Avery’s color is original, expressive and largely intuitively rendered, that is to say that it was never based on mechanical color theories or dogmatic aesthetic prescriptions (Fig. 4). Avery is able to utilize color itself as a means of suggesting and emphasizing mass, weight, and three-dimensional form in his paintings. The light, close-valued quality of Avery’s color emphasizes the interrelationships between the physical objects represented in the paintings and the light or space which surrounds them.

On Visual Humor

Avery’s jovial wit and sense of humor, mentioned in almost every description of his personality and apparent in many of his recorded statements, is also clearly evident within his art. Avery’s art exhibits a whimsical, witty quality, one achieved almost entirely through form rather than content. Avery possessed a wide vocabulary of squiggly lines, calligraphic brush strokes, and scratched or scraped designs creating an extremely witty dialogue through minimal design (Fig. 5).

Avery’s simplification of composition into a few basic color shapes and his repertory of humorous formal devices often led critics to comment on the innocent childlike nature of his work. Avery himself apparently had a strong admiration for the directness of expression and elimination of detail characteristic of children’s art, however, there is no evidence that he ever seriously studied works of art produced by children. Upon seeing an exhibition at The New School of Art done by children of the Greenwich House art class, Avery remarked,

We would all go more often to the galleries if such work was to be seen. These children express a spontaneity and joyousness in their painting, which all works of art should have for us. These paintings are an explosion of color arrangement. It is this color which particularly appeals to me rather than any literary content, which is, and should be, secondary.

— Milton Avery, 1945, From the Scrapbooks of Mrs. Milton Avery

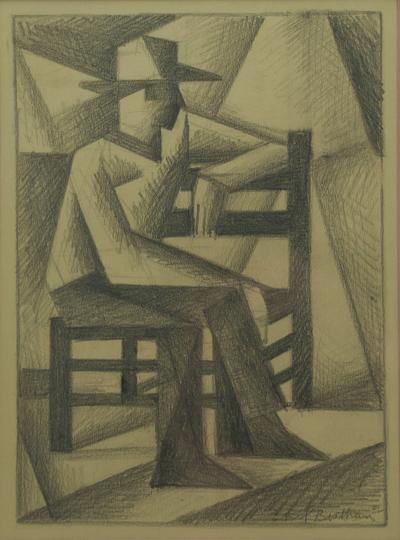

On Figure, Form & Perspective

Avery frequently gives his figures an exaggerated, almost awkward perspective. This exaggerated perspective—produced through a proficiency in drawing, never through mathematical or theoretical calculations—endows his figures with a sense of solidly occupying a pictorial space that often recedes dramatically into depth (Fig. 6).

Avery’s ability to suggest spatial depth and sculptural volume through precise linear drawing contributes to his ability to capture the unique identity of his subjects. This is particularly evident in Avery’s figure compositions where characteristic poses, features, and proportions are revealed almost completely through outline and silhouette.

Despite Avery’s rejection of conventional modeling in chiaroscuro, his figures retain an unmistakable sculptural quality—they possess a definite weight, mass, volume, monumentality, and ability to occupy the space in which they are placed (Fig. 7). However, it is Avery’s precision of outline and silhouette that defines the volume, proportions, and poses of his figures. Thus, those “factual accidents of the silhouette” are obviously not accidents at all. On the contrary they are precisely what is “all important to this kind of painting.”

On Landscape & Light

Avery recognized the early role careful observation of nature in the countryside surrounding Hartford, Connecticut, played in the production and development of his art. During the early years of his career, Avery painted in oils on canvas immediately from nature, only later beginning to paint from sketches.

Much of Avery’s ability to retain the singular identity of time and place clearly emerges from his concern for depicting the specific quality of light that illuminates his painted scenes (Fig. 8). Avery produces light-filled landscapes and seascapes through a direct use of close-valued color, seldom rendering the shadows produced by objects to convey the existence of a light source. The expression of particular conditions of light emerged as the primary focus in his extremely simplified compositions of the late 1950s. With a few brush strokes, Sun over Southern Lake of 1951 captures the visual impression of an evening sun across the surface of calm waters.

I always take something out of my pictures, strip the design to essentials; the facts do not interest me so much as the essence of nature. I never have any rules to follow. I follow myself. I began painting by myself in the Connecticut countryside, always directly from nature….I have long been interested in trying to express on canvas a painting with a few, large, simplified spaces.

— Milton Avery as quoted in Harvey S. Shipley Miller, “Some Aspects of the Work of Milton Avery,” Milton Avery Drawings and Paintings, 1977.

On The Sketch

Avery began to paint from previously executed works on paper only after many years of painting directly from nature. When he first changed his working method, he began with sketches and drawings, then moving to larger works on paper in a variety of media, and finally progressing to oils on canvas. This experience undoubtedly contributed greatly to his artistic development, particularly to his penchant for capturing the specific identity of his subjects.

As other painters had done for centuries, Avery only later in his development made sketches and drawings directly before his subjects, to capture—and later call back to memory—an initial visual experience. However, the multiplicity of miscellaneous detail is never re-imposed upon the image when it is translated from a small sketch into a larger work. In fact, perhaps, just the opposite: in the execution of the interim works on paper, Avery further simplified his compositions, eliminating illusionistic detail, and refining his color values (Fig. 9).

It is difficult to precisely date when Avery began to base his oils on canvas on previously executed works on paper. After a personal interview with Avery in 1943, an anonymous reporter paraphrased that Avery,

…works largely from sketches, getting an initial stimulus or reaction from nature. Before he starts a canvas, the idea has been pretty well crystallized so the actual painting is rapid, and retains a feeling of spontaneity, a quality achieved through long consistent practice, guided by fine sensitivity to color and balances.

— Milton Avery, in “An Interview with Milton Avery,” Art Student’s League Bulletin, April 1943.

On Abstraction & the Abstract Expressionists

While Avery’s art can never be described as completely nonobjective or purely abstract, it progresses toward an abstract quality through a process of radical simplification and severe reduction of the visual array. Although they can hardly be said to be illusionistic, his paintings are always to some degree representational. Avery’s canvases remain rooted in physical observation, and the best of them succeed in capturing that element of abstraction that always exists in reality. It is Avery’s recourse to his drawings and sketches that maintains the crucial balance between abstraction and representation, between the non-objectivity and realism (Fig. 10).

Avery’s early simplification of his compositions into relatively large areas of close-valued color, his use of gestural brushwork, his application of paint in thin stain-like washes, his diffusion and scumbling of edges of one color area into another, clearly had a strong influence upon the development of many members of the New York School.

…it was from Avery that Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, two members of the postwar New York School whose large, flat paintings anticipated and were a strong influence behind the emergence of “Color [Field] Painting,” got the idea of muffling, staining and washing thin paint onto the canvas in large areas of a single color. Avery, a representational painter, influenced the future development of abstract art….

— Andrew Hudson, “Avery Has Influenced Abstract in Still-Life,” The Washington Post, January 16, 1966.

Avery knew and frequently associated with both Rothko and Gottlieb as early as the late 1920s. Sally Michel wrote that Rothko, “dropped in almost every day to see what Milton was painting….Milton did a number of watercolors using these friends as models.” Sally also revealed, “Milton never formally taught anybody in his life….But Rothko and Gottlieb would come around and study his paintings and just absorb them by osmosis. One summer in Gloucester, Milton refused to show them what he was doing, because he felt they were becoming too dependent upon him.”

Decades later when in 1965 Avery died, Rothko expressed his great admiration at the memorial service for the artist and his art:

…This conviction of greatness, the feeling that one was in the presence of great events, was immediate on encountering his work. It was true for many of us who were younger, questioning, and looking for an anchor. This conviction has never faltered. It has persisted, and has been reinforced through the passing decades and the passing fashions…

— Mark Rothko, 1965, Eulogy at Milton Avery’s Memorial Service

This article is adapted from the catalogue for the exhibition Milton Avery & the End of Modernism, which was on view at the Nassau County Museum of Art from January 22 through May 8, 2011.

To view more of Milton Avery’s work click here

-----

Dr. Karl Emil Willers is director of the Nassau County Museum, Roslyn Harbor, New York.