Signature Works from the Westmoreland Museum of American Art: Picturing America

Fifty-seven works from the Westmoreland Museum’s permanent collection constitute Picturing America, a past exhibition that spanned two hundred years of American art, from colonial times to the mid-twentieth century, when America came into its own as the cultural capital of the world. Seen through the subject areas of portraiture, still life, and landscape painting, the artists represented serve as a survey of American art, beginning in the colonial period with paintings by John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West, and Charles Willson Peale, and completing the survey with early-twentieth-century modernists, Alfred Maurer, Milton Avery, and Sally Michel.

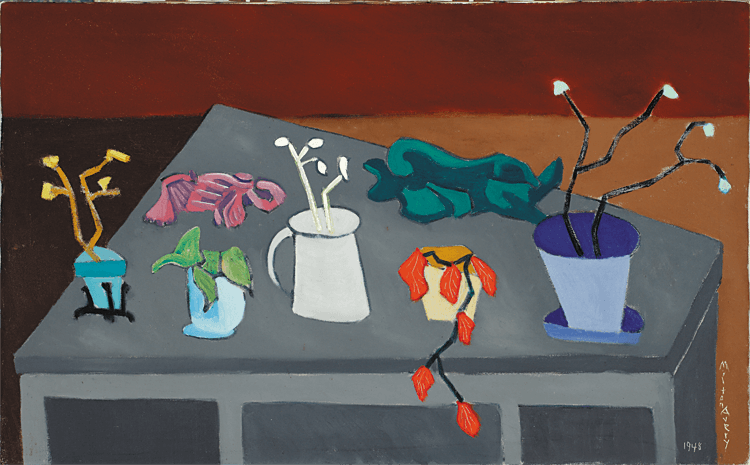

Milton Avery was a private man who enjoyed painting simple things that surrounded him. His wife, Sally, daughter, March, their dog Picasso, and friends figured prominently in his work. While still-life paintings were a relatively limited subject area in Avery’s body of work, he painted them occasionally throughout his career. In this composition, Avery’s sense of humor can be seen as readily as his sense of color and design. The plants take on almost human characteristics and their details are whittled down to the most basic shapes and patterns. Avery’s work is seen as a transition between realism and pure abstraction. His style can be compared to the European modernist Henri Matisse (1869–1954) whose works were readily available for viewing in New York City. Matisse and Avery shared a common attitude about art making and achieving balance and harmony in their paintings through the use of color, pattern, and shape. Avery lived and maintained a studio in the Dakota, the same Westside building where John Lennon would move to in 1973.

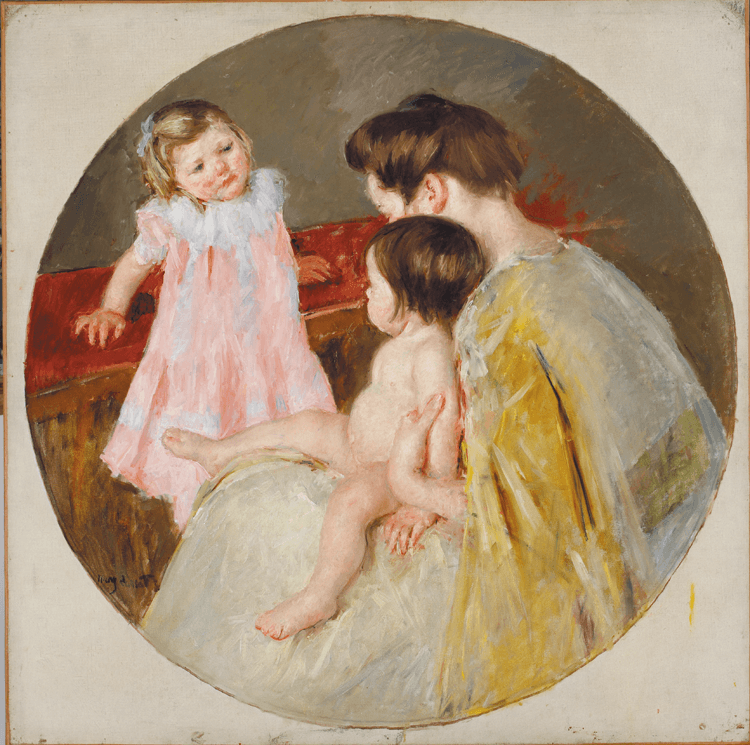

One of the most recognized names in American art, Mary Cassatt was born in Allegheny City—now the North Side of Pittsburgh, but grew up in Philadelphia. Introduced to Europe at age seven, Mary spent most of her life living as an expatriate in France, where her association with the impressionists provided exhibition opportunities and friendship. When Degas first saw her work in the Paris Salon of 1874, he said, “Here is someone who feels as I do.” Just three years later, Degas invited her to join the Independents, later called impressionists. The only American in the group, Cassatt exhibited with them in 1879, 1880, 1881, and 1886, and was accepted by them as an equal. This painting was originally created as part of a mural commission for the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg, one of a pair intended for the ladies’ lounge (now the lieutenant governor’s suite). The paintings were never installed because the artist, frustrated with government graft, withdrew from the project. The companion painting was formerly owned by the artist’s niece, but its current location is unknown.

The son of a writer on art and music, Guy Pène du Bois was both painter and critic. Exposed to the art world at an early age, he studied at the Chase School in New York, and later with Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller. An exhibitor in the 1913 Armory Show, Pène du Bois was a sophisticated insider whose subject matter showed society members at the theatre, art galleries, in restaurants, and in other urban settings. Placed in groups of two or three together, his subjects nonetheless always seem to be isolated. His work also had a sense of satire, sometimes subtle, sometimes quite direct. Du Bois simplified his forms by reducing them to pure geometric volumes and used broad areas of modulated color. Studio Window was painted in 1928 during a trip to Italy when Pène du Bois visited the small village of Anticoli, a site that attracted many artists. Du Bois shows an interior view with his model gazing out at a nondescript landscape. Her downward cast eyes and mouth convey a sense of melancholy and isolation. The window is more a barrier to the outside world than a transparent entrance to it.

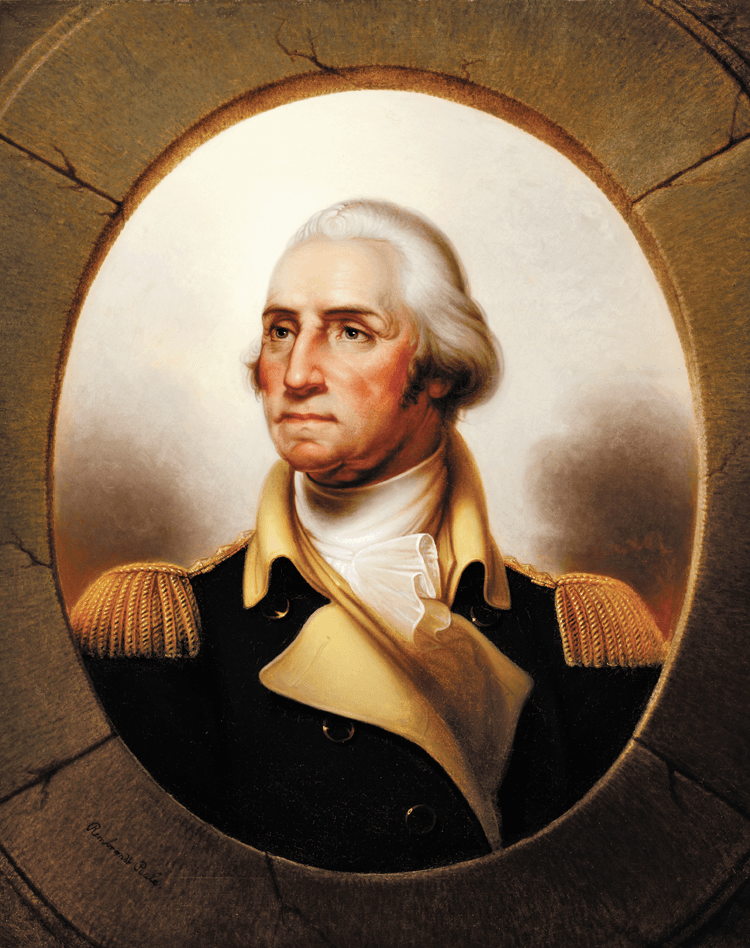

The Westmoreland’s first painting acquisition, Rembrandt Peale’s Portrait of George Washington, was purchased in 1958, fifteen months before the museum opening in 1959. Named after the seventeenth-century Dutch master, Rembrandt was the second son of Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), the patriarch of Philadelphia’s most influential family of artists. Trained by his father, the artist’s first and only sitting with Washington came in 1795, when Rembrandt was just seventeen years old. He created this portrait when nostalgia for the country’s first president and Revolutionary War hero was at its height, and hoped that the portrait—dubbed the “port-hole portrait” because of the trompe l’oeil oval stonework framing the sitter—would become the official likeness of the father of our country. Peale himself referred to it as “The Standard National Likeness,” his Patriae Pater. Although an image of Washington by painter Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) was chosen instead as the “official” likeness, Rembrandt Peale made good use of his painting by creating at least seventy-nine replicas of it at the request of various collectors.The portrait was chosen for the bicentennial exhibition, Three Centuries of American Art, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as one of the finest examples of this subject.

Alfred Henry Maurer has been called the “first American modernist,” having brought the ideas and styles of many early twentieth-century progressive European artists to this country in his own work. He was friends with the expatriate American collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein, who famously held salons in their Paris apartment, where European and American avant-garde artists and writers gathered. During the last two decades of Maurer’s life, he painted vibrant floral still lifes, landscapes, and figural studies—particularly heads and half-length portrait studies of women—using the vibrant color vocabulary of the fauves and the flattened overlapping planes and simplified forms of cubism in his compositions. Maurer’s first group of heads, often called “girls,” were not drawn from specific models but were more of an amalgamation, representing the successful merging of color, form, and composition into an intimate and emotional experience. In this painting, the girls’ elongated faces are simplified and masklike. With their large, soulful eyes, the two sisters peer out from the canvas and fix the viewer in their interactive gaze. The frame is unique in form, texture, and coloration because the artist made each one as a companion to the specific composition it housed.

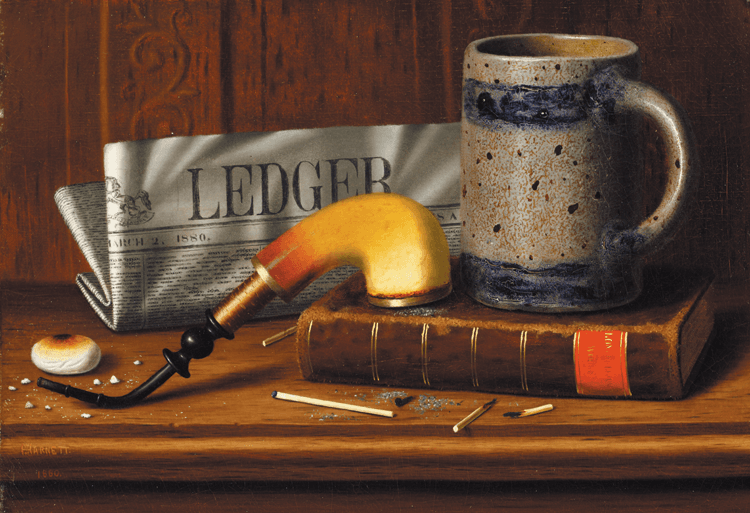

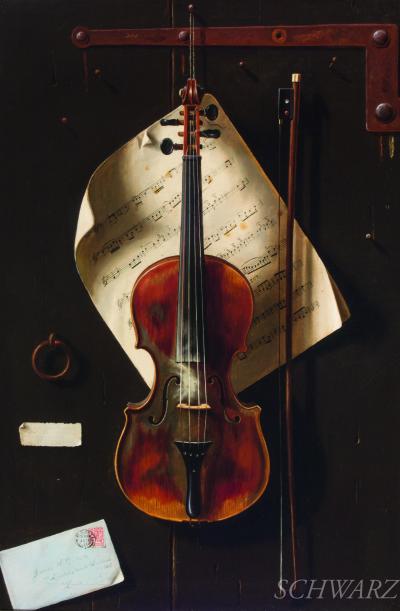

Irish-born, Philadelphia-raised William Michael Harnett began his artistic career as a silver engraver, which prepared him for the exacting detail that he accomplished in his oils of still life subjects. His forte was trompe l’oeil painting, in which his subjects are placed in a shallow picture plane and create the illusion of three-dimensionality by projecting into the viewer’s own physical space. Philadelphia Public Ledger is a prime example of Harnett’s expertise in painting in this manner. The objects are painted life size and seem incredibly real, as if the viewer could reach into the painting to extract them. His attention to detail demonstrates both his abilities with the brush and his acute powers of observation. He paints the mug with the right heft and texture, the pipe appropriately delicate, and creates a worn line on the book showing its use and age. The bits of ash and used matches give the arrangement a sense of the human touch that went into creating it. Harnett would have you believe that the owner of the objects left the scene a mere moment before, thus composing a near portrait of the person who owned them.

Apples in a Brown Hat shows the artist’s favorite fruit, which Levi Wells Prentice painted many times in different ways—on a tabletop, under a tree, or still growing on a bough. His apples are not glorified, beautiful, or perfect; instead, they appear as they are in nature, complete with bruises, gouges, and bumps. Self-taught as an artist, Prentice learned by looking at reproductions and the work of other artists. He developed a style of painting marked by an intense realism, using rigidly delineated hard-edged forms and high-key color combinations. Prentice, who grew up on a farm in northern New York State, painted in the Adirondacks early in his career. When he died, his obituary in the Philadelphia newspaper noted that: “The world at this time is in sad need of men of his caliber, men who worship at the shrine of truth and beauty and can look beyond petty acquisitions of the day to scenes of grandeur and glory which will never pass away.”

Known as one of America’s foremost impressionist painters, Childe Hassam was the son of a Boston antique collector. Like many of his contemporaries, he maintained a studio in New York City but vacationed during the summer months, spending time in New England. His favorite retreat was Appledore Island, off the Maine–New Hampshire coast. The Outer Harbour dates from the prime of Hassam’s painting career and shows his interest in light, brilliant color and a painterly brushstroke. The almost square format, high perspective from which the harbor is viewed, and the grand expanse of ocean beyond combine to give the illusion that Appledore was completely isolated in the ocean, when in fact it was relatively close to the mainland. Filled with light and air, the warmth of the atmosphere radiates through a shimmering rainbow of colors. Broken brushwork creates a prismatic effect, further animating the surface.

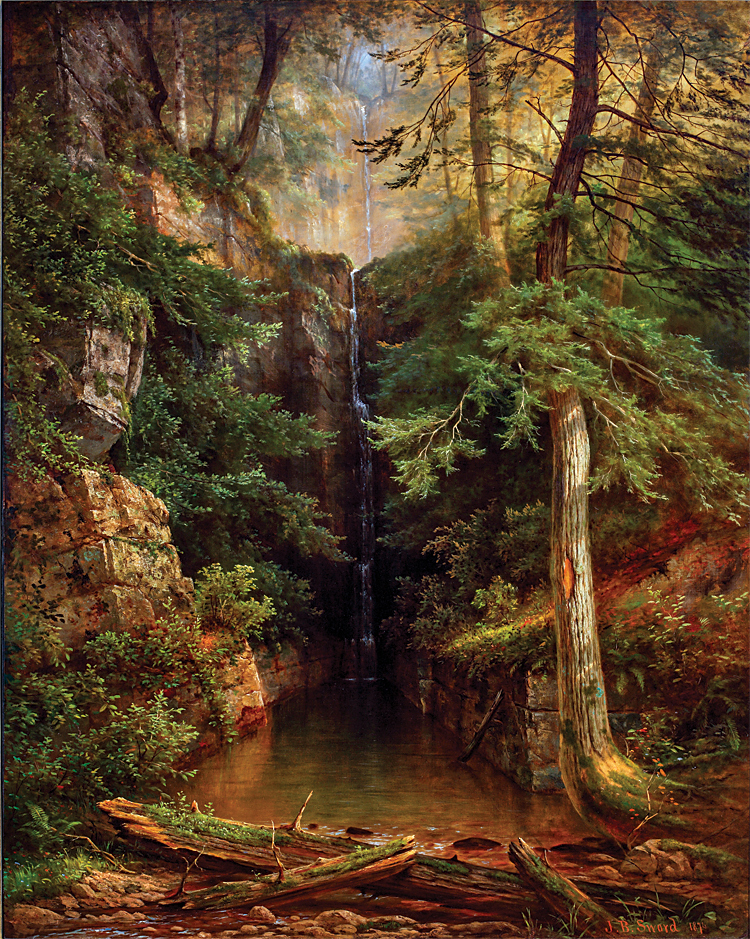

This ambitious canvas may be the most important work by Philadelphia-born James Brade Sword, a member of the last generation of Hudson River School painters, active in the late nineteenth century. Unseen by the public in over a century, the painting descended by inheritance through two private collections before being rediscovered at auction, just prior to entering the museum’s collection in 2008. The Falls still exist today and the view is much the same. Located near Milford, Pennsylvania, it is one of the highest waterfalls in the Pocono Mountains. Silver Thread Falls may have been one of two paintings Sword painted in preparation for exhibition during the nation’s centennial in 1876. The subject records the majesty of America’s wilderness, a theme much celebrated as the nation approached its one-hundredth birthday.

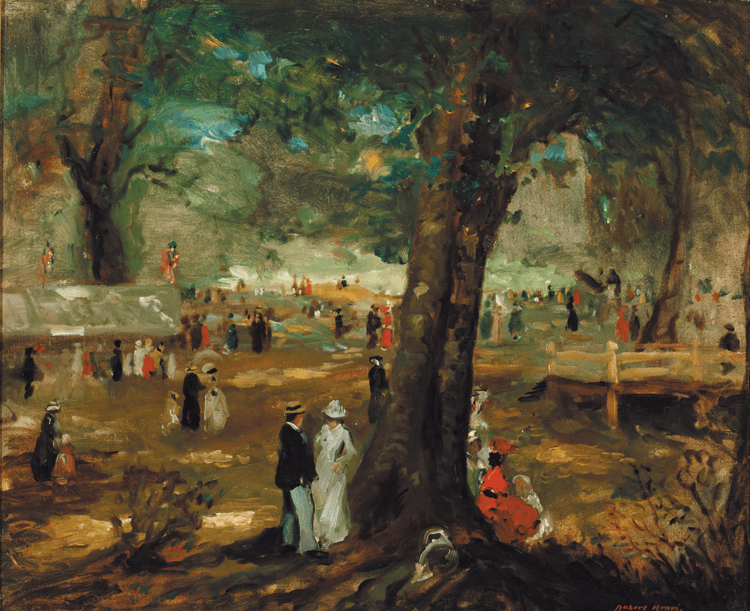

Robert Henri was born Robert Henry Cozad but changed his name after his father killed a man in self-defense during a dispute between ranchers in Nebraska. Pronounced “Hen-rye,” it was as if in one action he was both saluting his French heritage and proclaiming his American citizenship. Henri moved to Philadelphia and later New York, where he became a charismatic painter, teacher, and ardent spokesperson for artistic independence in an era when tradition dominated the art market. He was the leader of “The Eight,” an association of artists seeking artistic freedom, and of the Ashcan School, named for their interest in painting New York’s working-class neighborhoods in the lower East Side. Demonstrating his influence, the book Henri wrote in 1923 titled The Art Spirit is still used by art students today. Henri’s first wife was from northeastern Pennsylvania, and it was on a visit to her parent’s home that he painted Picnic at Meshoppen.

George Inness grew up on a farm in rural Newark, New Jersey, receiving only limited artistic training that included an apprenticeship in the studio of the landscape painter Regis Francois Gignoux (1816–1882) in New York. At a time when his contemporaries, the painters of the Hudson River School, were striving to create an American art style based on the direct study of the untamed American wilderness, Inness was studying the work of European masters, preferring the civilized landscapes of Europe. After meeting Swedish scientist-turned-mystic Emanuel Swedenborg in 1860, Inness’s style changed. He began using rich, luminous colors, blended together to create vaporous, atmospheric landscapes that evoke mystery and reverie, rather than reality. His later works fused sky with earth and trees with landscape to reveal God’s presence. Inness’s keen powers of observation now evidenced the fact that nature was constantly in movement and no one moment could be captured in paint. In The Coming Shower, likely painted near Perugia, Italy, Inness evokes the temporary quality of light effects and transitory weather conditions in nature. The dramatic, brightly lit scene is yet diffused, to indicate the fleeting nature of the storm. The poeticism of his later work achieved for Inness significant critical acclaim.

While studying in Paris, William Zorach met fellow student Marguerite Thompson, an accomplished artist who had been in Paris for over two years. They married in 1912 and created a strong artistic partnership that lasted for fifty-three years. While they collaborated on some work during their years together, they remained individual artists.In this sculpture, with subtle curves and minimally incised details, William Zorach portrays the family cat at rest, relaxed yet alert and ready to pounce, with head slightly raised, as if something has just caught its attention. The mottled patina on the sculpture is reminiscent of the texture and variegated coloring of a cat’s fur.

Located in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, the Westmoreland is the largest repository of southwestern Pennsylvania art in the country. George Hetzel led a group of his fellow artists dubbed the “Scalp Level School” to paint the bucolic landscape in Scalp Level, near Johnstown, much like Thomas Cole introduced his friends and followers to the Hudson River valley three decades earlier. These works serve as counterpoints to the scenes of industry that depict the Big Steel Era of Pittsburgh, illustrating the transformation of the American landscape from an agrarian society to an industrial one. Other artists, Christian Walter, Malcolm Parcell, and Austin C. Wooster, are placed in context with their national contemporaries. Bronze sculpture by Paul Manship, Harriet Frishmuth, and William Zorach add a third dimension, reflecting the working methods of three distinctly different artists.

The Westmoreland Museum of American Art was founded in 1959, due to the generosity of Mary Marchand Woods, the widow of Cyrus E. Woods, a distinguished statesman and diplomat. When Picturing America: Signature Works from The Westmoreland Museum of American Art was installed, it providee the public access to part of the collection while The Westmoreland was undergoing a major expansion and renovation, completed in 2015. The exhibition was on view at The Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York, through January 4, 2015, and was curated by Westmoreland Museum of American Art Chief Curator Barbara A. Jones, and, at The Hyde Collection, by Hyde director Charles A. Guerin. The exhibition was sponsored in part by the Town of Queensbury, Queensbury, New York. Visit Lake George/Warren County, New York, The Adirondack Trust Company, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. For information visit www.hydecollection.org or call 518.792.1761.

Barbara L. Jones is chief curator of the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.