Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Her Folk Art Museum

The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum Celebrates its 60th at the Winter Antiques Show

As a pioneering collector of American folk art, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (Fig. 1) assembled a body of objects that continue to fascinate museum visitors and scholars alike. Her collection became the foundation of the museum that bears her name, the oldest continuously operating institution in the United States devoted solely to the study and appreciation of the field.1 She donated her folk art to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1939, which officially opened the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in 1957. This year, Colonial Williamsburg celebrates the sixtieth anniversary of the museum with an inaugural exhibition at the Winter Antiques Show in New York City. The loan exhibit, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum: Revolution and Evolution, highlights fifty-one objects selected from Mrs. Rockefeller’s collection and pieces acquired over the course of the past six decades and celebrates the extraordinary achievements of the museum’s namesake.

Abby Aldrich was one of ten children born to Senator Nelson Aldrich and Abby Chapman Aldrich of Providence, Rhode Island (Fig. 2).2 Senator Aldrich, a successful and largely self-made man, had an extensive library and was deeply interested in and collected paintings. Abby’s extensive knowledge of the arts began in her youth with family trips to cultural centers such as Washington, D.C. Later, she traveled to Europe where she visited many of the notable museums and galleries in London and Paris. On her return, she met John D. Rockefeller Jr. and, in October 1901, they were married. With the couple’s fortune connected to oil, the Rockefellers supported many causes, including arts and education initiatives.

Abby Rockefeller’s interest in American folk art was tied directly to her appreciation of the work of modernist painters and sculptors. A founder and active supporter of the Museum of Modern Art, she took great pleasure in discovering and acquiring the work of unrecognized talent, and knew and patronized many of the exhibiting artists.3

At the same time that modern art was challenging traditional notions of art, a small circle of artists, dealers, collectors, and scholars began to recognize the importance of American folk art.4 Painter Henry Schnakenberg’s 1924 exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club was an early example. Schnakenberg was one of the modern artists who embraced folk art both as visual inspiration and as a collector. These painters and sculptors saw the abstract qualities and distortions of folk art as akin to their own work. Among the artists who started collecting folk art were members of the Ogunquit artist colony in Maine.5 Edith Gregor Halpert, who would become a leading New York dealer in the work of emerging modern artists, stayed at Ogunquit during the summer of 1926 with her husband, painter Sam Halpert, there developing an appreciation for folk material. She opened her Downtown Gallery in Manhattan the same year, representing the work of avant garde artists. Two years later, Abby Rockefeller visited Edith’s gallery to purchase artwork by living modernists represented by Halpert, and the two commenced a long association.6 It was at this time that Abby expressed her passion for art in a 1928 letter to her son Nelson: “It would be a great joy to me if you did find that you had a real love for and interest in beautiful things,” and explained that art, “enriches the spiritual life and makes one more sane and sympathetic, more observant and understanding.” 7

Rockefeller’s first visit to the Downtown Gallery occurred as she and her husband were increasingly absorbed in the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg. John Jr. was introduced to the colonial capital in 1924 during a trip to the region with his family. There he met Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, a local Episcopal minister who passionately argued for the preservation of the town, which had fallen into decline after the relocation of the capital to Richmond. Goodwin believed that Williamsburg was an integral part of the history of America and convinced Rockefeller to fund its restoration. Abby quickly recognized that folk art, mostly nineteenth-century in origin, was yet another aspect of American material and cultural life worth preserving. She viewed the so-called primitive works as a logical historical background for her already sizeable collection of modern American art, and she saw folk art as linked to the work of colonial Americans. Rockefeller’s expanding collecting interests aligned with the opening of Halpert’s American Folk Art Gallery, a new space within the Downtown Gallery, where Halpert was able to offer Rockefeller and other early folk art collectors a steady supply of paintings, works on paper, and sculpture (Fig. 3).

- Reuben Law Reed, Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown, Acton, Mass., 1860–1880. Oil and gold paint on canvas. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1931.101.1). Rockefeller’s love of pictorial art extended to genre pictures and included paintings such as this iconic image of Washington and Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown rendered by a descendant of a Revolutionary soldier, whose life-long interest in history prompted him to recreate his own version of the military events on canvas.

- The Old Plantation, attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, South Carolina, ca. 1785. Watercolor on laid paper. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1935.301.3). This well-known watercolor was acquired in 1935 by Holger Cahill during a trip south. New research identifies the amateur artist as a South Carolina civic leader and planter. The sensitive portrayal of the artist’s slaves participating in a West African stick dance is most likely the earliest surviving portrayal of the subject.

During her lifetime few people realized the scope of Abby Rockefeller’s involvement in the arts. She shied away from publicity and did not mingle with other collectors. Yet, she was willing to share her folk art with the widest possible audiences, and some of the paintings and a number of sculptural works in her collection were shown anonymously at the Newark Museum in 1930 and 1931. The following year, Rockefeller offered to loan Colonial Williamsburg her growing collection, which she modestly described as “small” and made up of “pictures painted by our great grandmothers and great aunts, a few by men, between 1790 and 1820 or 30.” 8

In the meantime, she agreed to exhibit 174 pieces from the collection, again anonymously, at the Museum of Modern Art, in the first comprehensive exhibition of its kind: American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900. After its New York debut, the exhibition traveled to six cities and was both enormously popular and critically acclaimed. The national exposure meant that for the first time, people started to recognize the importance of pictures and sculpture that had previously lain neglected among family heirlooms. Holger Cahill, who curated the Newark and MoMA shows and authored the Art of the Common Man exhibit catalog, was engaged by the Rockefellers to advise Abby on American folk art and search for potential acquisitions.9

- Weathervane, New England, possibly Conn., ca. 1850. Sheet iron. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1932.800.3). The second largest component of Rockefeller’s collection was carvings, weathervanes, and other types of sculpture. The weathervanes represent both handmade and manufactured types. This snake, in its wonderful abstracted form, was most likely the product of a local blacksmith who combined useful purpose and whimsical design.

- Memorial for Polly Botsford and her children, possibly Newtown, Conn., ca. 1815. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Collection of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller; Gift of the Museum of Modern Art (1933.304.1). Stylized forms similar to those seen in modern painting are used to create the pictorial elements in this composition.

By the end of the show, plans were complete for Rockefeller’s loan of the principal part of the collection to Colonial Williamsburg, where it would be exhibited in the restored Ludwell-Paradise House on the centrally located, historic Duke of Gloucester Street (Fig. 4). Edith Gregor Halpert worked with Cahill and Rockefeller, making final selections and plans for the exhibit, which opened in March 1935 and met with an appreciative response from both the public and the press.

As the Rockefellers’ personal involvement in the restoration of Williamsburg and the exhibition of Abby’s folk art collection intensified, the family decided to establish a residence in Virginia. In November 1936, they moved into Bassett Hall, an eighteenth-century house that the couple came to treasure for its “peaceful and homelike qualities.” 10 Among the traditional English and American antiques and modern chairs and beds were approximately 125 American folk art pictures and decorative objects that Abby selected specifically for their personal enjoyment. Set alongside highly formal furnishings was a mix of weathervanes, pottery, chalkware, nineteenth-century portraits, needlework, wood carvings, and hooked rugs and bed covers crocheted by local women, including Abby herself. The result was a home with rooms that were inviting, relaxing, comforting, and visually pleasing. Today, the house is preserved much as it was during the Rockefellers’ occupancy, and it greatly helps us to understand Abby’s tastes, lifestyle, use of folk art, and the wide variety of art she collected. Like the collection of folk art that was on loan to the Foundation and on view at the Ludwell-Paradise House, the objects chosen for Bassett Hall reflected Abby’s keen eye for strong design, color, and fine workmanship, and therefore can be considered a second museum collection. Bassett Hall was conveyed to Colonial Williamsburg after John D. Rockefeller III’s death in 1978, and remains an exhibition site as part of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Oliver Wight and Harmony Child Wight (Mrs. Oliver Wight), attributed to the Beardsley Limner, probably Sturbridge, Mass., 1786–1793. Oil on canvas. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Museum Purchase (1957.100.9 and 1957.100.10). Over half of Rockefeller’s folk art collection consisted of paintings in oil, ink, and watercolor. The companion portraits of the Wights reign supreme in the small body of work attributed to The Beardsley Limner. The pair was acquired the first year of the museum’s operation from M. Knoedler and Company and was previously owned by influential collector Isabel Carleton Wilde.

- Quilt, Pennsylvania or Ohio, 1920–1960. Cotton. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Museum Purchase; The Antique Collectors’ Guild (1979.609.2). Although she collected a number of schoolgirl needlework pictures, Rockefeller did not assemble significant quantities of quilts. The first full-size example was not acquired by the museum until 1972. Despite this, the textile collection has grown significantly over the past few decades to include approximately 120 noteworthy pieces.

The Rockefellers’ love for the town and the Restoration project made Williamsburg a natural choice for the permanent home of Abby Rockefeller’s American folk art collection. John Jr. would later write that “these pictures meant so much to Mrs. Rockefeller and because she herself hung them in Williamsburg, I would personally be very unhappy to have them go elsewhere.” 11 In 1939, Abby Rockefeller donated the majority of the collection to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The Ludwell-Paradise exhibition remained open to the public until January 1, 1956, well after her death in 1948. The collection was then removed from view and made ready for installation in a purpose-built museum. On March 15, 1957, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection opened to the public as a memorial to Abby’s pioneering interest, and became the country’s first museum devoted exclusively to American folk art.

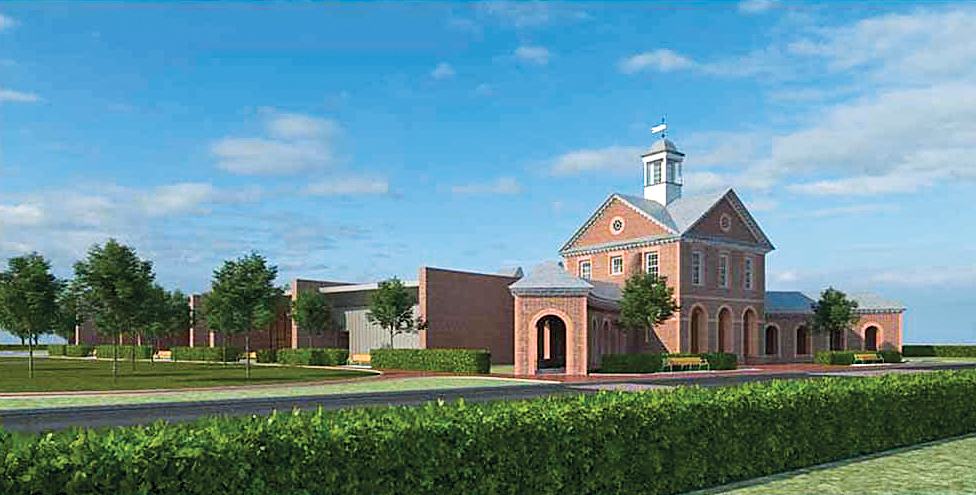

The lure and intrigue of discovery delighted Abby Rockefeller. Given her deep-rooted belief in the universal value of art, had she not been able to share it, she might not have collected it at all. The museum collections have expanded since her death through the work of various curators and directors, principally in areas such as textiles and pottery, forms that Rockefeller did not collect extensively. Today, the museum represents its founder’s interests and collecting activities, as well as those of Foundation staff, and the collection has grown exponentially from Rockefeller’s gift of 420 objects to over 7,600 works. In April 2017, Colonial Williamsburg will break ground for a $40 million expansion of its art museums, which will add 65,000 square feet with a twenty-two percent increase in gallery space, providing for increased opportunities to display Mrs. Rockefeller’s folk art collection and engage visitors in the telling of America’s story (Fig. 5).

|

|

- Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Museum Purchase (2003-171). Although she acquired pottery for her personal use at Bassett Hall, Rockefeller’s gift to the museum included only one example of the form. The museum did not begin to collect this material in earnest until the 1970s, most likely in anticipation of the bicentennial. Today, the collection includes more than 150 ceramic objects and continues to evolve. This slip-decorated earthenware dish from Alamance County, North Carolina, represents present-day collecting efforts to include works from inland regions of the country.

As the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation enters the 60th anniversary year of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, we reflect on the remarkable spirit of the museum’s namesake and are reminded of the indelible mark that Abby Rockefeller made on the field of American folk art. She elevated a body of material that had long been dismissed as homespun craft to a nationally-recognized and highly-regarded form of American art. Mitchell Wilder, Colonial Williamsburg’s vice president and director of collections in 1957, said of Abby Rockefeller, that her “judgment and wisdom gave her vision which was beyond the immediate and the obvious.”

- Fig. 5: Plans are well underway for the expansion of the Art Museums (The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, together known as the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg) to include eight thousand square feet of new gallery space, a street-level entrance, expanded guest amenities and programming, and new and upgraded mechanical systems.

The loan exhibition Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum: Revolution and Evolution is on view at the Winter Antiques Show, Park Avenue Armory, New York City, from January 19–29, 2017. For more information, visit

www.winterantiquesshow.com or www.colonialwilliamsburg.com.

-----

Laura Pass Barry is the Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture, at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

The objects in this article will be on view in the loan exhibition.

This article was originally published in the 17th Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect. The images that follow were not published in the magazine and are an additional feature available on Incollect. They will also be at the loan exhibition.

Read related articles: Patriotic Folk Art at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and A Touch of Whimsy in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

2. Mary Ellen Chase, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1950).

3. Rockefeller was introduced and inspired to collect modern art after visiting the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as The Armory Show of 1913. The Show has long been credited with having a profound effect on American art.

4. A few of the early influential dealers and collectors include Isabel Carleton Wilde, Juliana Force, Electra Havemeyer Webb, and Elie and Viola Nadelman.

5. The Ogunquit artists were inspired by a simplified form of American art that was reflective of the country’s national character. See Elizabeth Stillinger, A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art, 1876–1976 (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), 159–169, for a more detailed information on the Ogunquit Colony. Stillinger’s book is one of the best resources on the history and development of American folk art appreciation.

6. Lindsay Pollock, The Girl with the Gallery, (New York: Public Affairs, 2006), 95.

7. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller to Nelson Rockefeller, January 7, 1928. Copy of letter, AARFAM research files.

8. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller to Colonel Arthur Woods, February 10, 1932, AARFAM research files.

9. Cahill spent eighteen months in 1934–1935 travelling in search of folk art for Rockefeller’s collection. Ultimately, he discovered and helped to acquire more than forty objects that are now part of the museum.

10. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller to David Rockefeller, November 1, 1943. Copy of letter in Bassett Hall research files.

11. Statement from John D. Rockefeller, Jr. from January 13, 1953 quoted in a memo titled: The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection, A Summary of Development, May 17, 1975. AARFAM research files.

12. Many thanks to Elizabeth Stillinger for clarifying Cahill’s role in the discovery of Edward Hicks’ work.