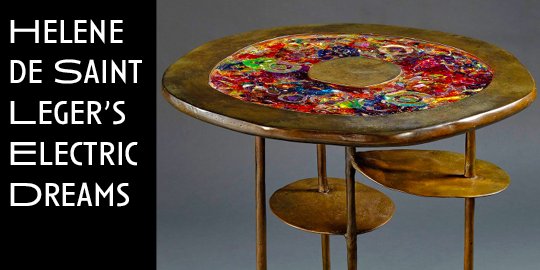

The Untamed Genius of Paul Evans

|

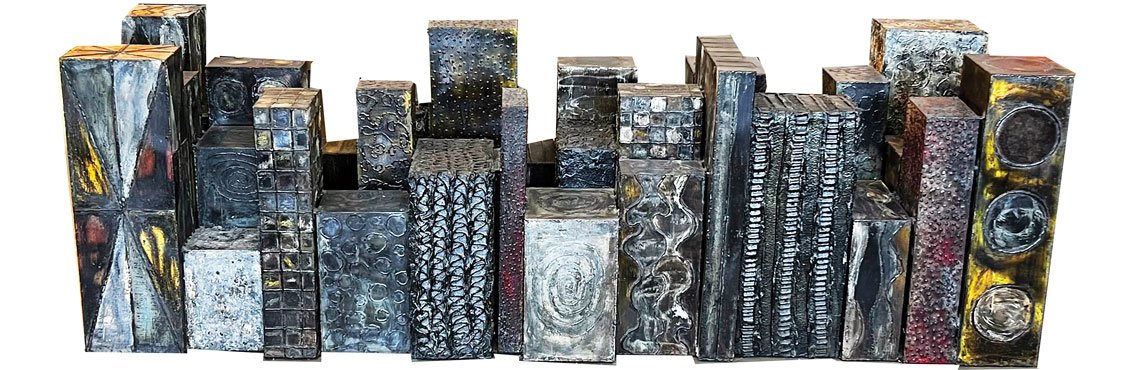

“Skyline Series” dining table, 1973. Welded polychromed and patinated steel. From Milord Antiques on Incollect. |

|

Paul Evans’ furniture designs elicit mixed, often extreme reactions.

There are those who point to the American-born designer’s originality and superb craftsmanship with metal. Then there are others, less generous, who recoil at the roughness around the edges, finding his designs heavy, brutal, and ugly.

Evans’ highly individual, expressive metal objects are in many ways the opposite of the refined sensibility of American design in the second half of the 20th century — Karl Springer, for example. Yet his unique combination of fine execution, materials, and craftsmanship has proven to be not only the basis for an enduring contribution to the history of American furniture design but a thriving contemporary market.

|

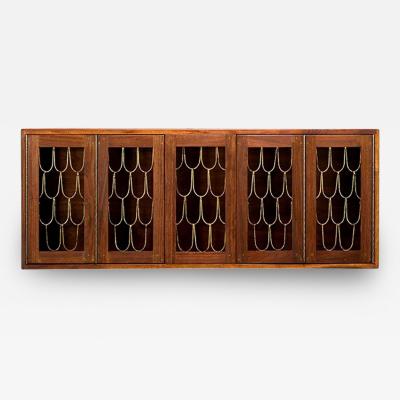

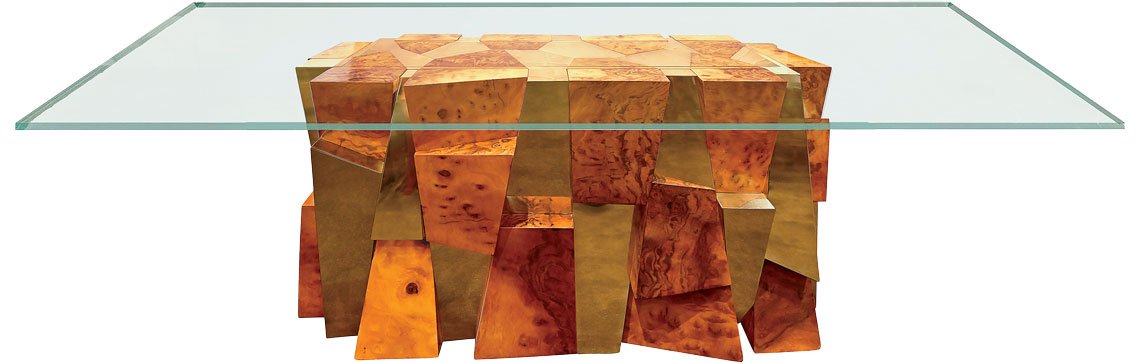

“Faceted Dining Table” for Directional Furniture, 1970.Walnut burl and polished brass with thick glass top. From Lobel Modern on Incollect. |

|

Today Evans is among the most collectible of 20th-century American makers. His designs have sold at auction and galleries for more than $250,000. His success rests in part on his singular, distinctive aesthetic vision but also on the fact that he died in 1987, at age 55, creating a scarcity of his bespoke, hand-made pieces.

“In the last 15 or 20 years, the value of his pieces has steadily increased due to the continued interest generated by art collectors and interior designers,” says Francis Lord from Milord Antiques in The Gallery at 200 Lex powered by Incollect in the New York Design Center, and in Montreal, who is a longtime dealer in Evans. “The rarity and unicity of his pieces lend itself perfectly to a discerning art collector or designer wanting to place an important work of art over a piece of furniture. In these current times of high-end contemporary creative designs stemming from talented creators from all over the world, Evans' pieces hold their own in this competitive market.”

Driving demand is also an increasingly global market for the designer. “We’ve had Paul Evans pieces in our collection for the past 15 years and have sold pieces to a wide range of clients,” says Lord. “A piece was purchased by an important design firm for a Louis Vuitton store in Rome, while a disc bar, a credenza, and a wall unit were purchased by a collector to decorate a chalet in Gstaad, Switzerland. We have shipped pieces to Milan, London, Paris, L.A., New York, Seoul,” he says.

Lord recently had three Evans pieces on display at The Winter Show in New York, including a disc bar, a stool, and a beautiful Skyline table. “In my collection,” he says, “I consider Paul Evans furniture to be blue-chip inventory,” but admits that for some collectors Evans is still something of an acquired taste, not to mention the escalating price points for rare, important pieces that find their way onto the market. “The more people are aware of his work the better they become aware of the quality,” he says.

| |

“Sculpted Metal Collection” PE-128 Stalagmite cocktail table for Directional Furniture, 1979. From Hobbs Modern on Incollect. |

Evans’ designs are often associated with the period style in architecture, design, and art known as Brutalism, which emphasized materials, textured surfaces, and making visible construction processes. The term was first applied to architecture in the early 1950s and is believed to originate from the French “beton brut,” meaning “raw concrete,” used by architect Le Corbusier to describe the emerging geometric style of buildings in the 1950s with raw and expressive poured concrete finishes.

Evans is certainly at the forefront of the Brutalist design movement that took place in the 1960s in America, though the affiliation is somewhat misleading given inspiration for his pieces came from many sources. The American Craft Movement of the 1960s and 70s celebrated individual creation, artisanship, and craftsmanship as opposed to mass production and Evans saw himself as a part of this tradition. He was also paradoxically inspired by advanced modern art, architecture, and the modernity of American cities, blending hand-craftsmanship with science and new technology.

|

“Deep Relief” sculpted credenza, 1969. Four hand-welded steel doors with hand-painted enamels and three slate tops on nailed metal surface. From Greenwich Living Design on Incollect. |

|

Argente Series custom king-size canopy bed, circa 1968. Welded waves of polished and matte black aluminum. Concealed inner rail for curtain, the top ledge will support a fabric canopy or mirrored ceiling. From Todd Merrill Studio on Incollect. |

Evans studied at the Cranbrook Academy of Art then settled in the semi-isolation of rural Pennsylvania (his neighbor was George Nakashima) and began to experiment with making sculptures as well as furniture using metals. In 1964 he began a fruitful, life-long partnership with Directional Furniture, a prominent manufacturer, who over the subsequent decades marketed and sold several of his custom furniture lines — the most famous being the Argente series and the popular Cityscapes series.

Evans may have worked with industrial metals but insisted on finishing them finely. “Evans had a hands-on philosophy to the fabrication of all his pieces,” says Evan Lobel of Lobel Modern in New York. “Generally his pieces were made to order, with everything handmade by him or finished by hand under his strict supervision.” Many are one-of-a-kind custom pieces, very often signed and sometimes even dated.

His most coveted designs usually combine steel or aluminum with beautiful enamels or semi-precious metals placed on the front and doors. “He invented unprecedented techniques and materials to create his sculptural pieces, often using acid-patinated and enameled, welded steel, or sculpted bronze resin and various metal patchwork designs,” Lord says. He also liked to use gilding, frequently taking rough pieces of metal and then gilding parts of them to create visual tension and contrast.

|

“Cityscape II” cabinet, 1970. Chrome-plated and brushed steel facets, dark brown lacquered wood top. From Maison Rapin on Incollect. |

|

“People do not gild things unless they consider them to be art,” Lobel says. “What he was doing was completely original — even at the time many important collectors were buying his work.” His innovative use of metal meant ultimately no two pieces were the same (this is another important reason why he is so collectible) and is probably best exemplified in the sculpture front cabinets followed by the sculpture top coffee tables — these tend to be the most hand worked and technically complex, combining gilded, welded, polychromed and patinated steel, bronze, copper, pewter, brass.

Nick Pizzichillo from Greenwich Living Design recently acquired a large deep relief sculpted sideboard which is on display in their 15,000-square-foot gallery in the Stamford Waterside Design District. “This massive four-door credenza is finished with vertical fragments of hand-painted enamel doors, nailed metal patchwork details, a three-piece slate top, and opens to reveal a faux tortoise red lacquer wash,” Nick says. “Having been in the decorative arts world for over 40 years, this is hands down one of the most unique pieces we have had the pleasure of presenting.”

“Evans’ original studio furniture is a combination of abstract sculpture and practical design,” says Maddie Sadofski from TFTM in Los Angeles. She points to the way in which all of the handcrafting is displayed in welds and nails so that viewers can fully appreciate the sculptural qualities of the pieces. “Handles and latches are concealed,” she says, “becoming part of the integral design. Glass table tops are used on coffee and dining tables so that all of the abstract sculptural images become visible.”

|

Wall-mounted Disc Bar model PE-122 for DIrectional Furniture, 1970. Sculpted bronze composite, two doors, interior fitted with one cabinet with key and one drawer, each with sculpted bronze composite surfaces plus two adjustable shelves. From Michel Contessa Antiques & More on Incollect. |

|

Wavy Front Cabinet, 1973. Welded, gilt, polychromed and patinated steel, slate top. Four handcrafted doors with undulating connections, two main storage compartments, three shelves, two silverware drawers. From Donzella on Incollect. |

Sadofski has a monumental Skyline table base now in the TFTM showroom in Los Angeles, and it is displayed without glass so that the client can customize the tabletop size, she says. “Many people have asked if it is a sculpture. Others recognize it as a table base, and then, much like an abstract sculpture, some ignore it entirely.”

Evans’ pieces tend to make an immediate, striking visual statement, and among the most recognizable and coveted by collectors is the Argente series (the French word for silvery) created in welded aluminum during a brief 6–7 years period starting in 1965, due to the expense of producing them. Sold and distributed through Directional Furniture, the pieces combine irregular, vertical and horizontal welded sections of reflective silver with opaque black aluminum, frequently decorated with pictographic drawings.

The craftsmanship of the Argente series is breathtaking — each piece is like a jewel, an exquisite work of art. “Since the turn of the 21st century, a fresh look at Evans’ extraordinary legacy has created a new appreciation and a thriving market fueled by a passionate group of fervent collectors,” says Dallas Dunn, gallery director at the Todd Merrill Studio in New York where, in 2020, she helped organize an exhibition of custom Argente works. In 2017, Todd Merrill Studio sold Evans’ first forged steel and sculpted bronze disc bar, from 1968, for a then-record price of $200,000.

|

|

Set of 10 PE 105/106 Series dining chairs for Directional Furniture, 1965. Sculpted epoxy with bronze over steel. From circa20c on Incollect. |

Ken Bolan from Ken Bolan Studio in London bought his first Evans piece in 2006 and has bought, sold, and even lived with them ever since — today, in his London home, he has a sculpted bronze Evans wall console and a matching mirror, and in his previous apartment, he had an Argente collection wall console. “I view his pieces as sculptures and that is what I find exciting about him as a designer. Anybody looking to create their aesthetic with artistic furniture would have to look at Evans, as he hits both ends of the spectrum with functional furniture blended with sculpture.”

Nicole and Ryan Hobbs from Hobbs Modern in San Diego agree with Bolan, pointing out that this very juxtaposition between design and sculpture is what makes Evans and his pieces so unique but also alluring and compelling. “He smashes the boundaries that define art, sculpture, and furniture, eliciting debates between collectors, admirers, and peers as to whether his pieces are good or bad, or are ugly or beautiful,” said the dealer couple. “Conversation always elicits an appreciation for his work and why we at Hobbs Modern always look for his pieces. We love designs that bring about conversation and Evans' work does just that — it is functional art.”

|

PE-20 cube tables from the Sculpted Metal Collection for Directional Furniture, 1968. Welded steel with polychrome enamels, gilding and inset slate tops. From Solo Modern on Incollect. |

|

Skyline Series table base, 1970. 44 hand-welded sections with gilded and polychrome enamels. From TFTM on Incollect. |

Nicole and Ryan Hobbs see Evans as a precursor of much high-end artistic studio furniture on the market today. Nina Malka from Maison Rapin in Paris agrees. “His combination of tradition and modernity is still alive today in the work of many artists who promote and use ancient craftsmanship to create new aesthetics,” she says and points out that Evans’ pieces are more sought after today than during his lifetime.

Evans is an anomaly, a unique, thorny figure in the history of design. That was his genius and in a strange twist of fate, perhaps his greatest and most enduring legacy. He pointed the way forward for designers to be artists by an appreciation, in one final paradox, of the virtuosity and craftsmanship of the past.

|